He’s just not seeing you. That young dude behind the bar, seemingly whenever you go to a bar. You wait, patiently, and wait. He throws to the guy behind you, “what’ll it be, mate.’ As if you’re not there. As if he just hasn’t clocked you.

The rage builds. You control your voice. Turn to the guy behind you with a tightening smile and say, “excuse me, I was next.” Gentleman number two looks bewildered, apologetic. He hadn’t clocked you either.

Welcome to cronedom. The age of invisibility. I’ve stepped into it, only just on the wrong side of 50 and quite possibly shrinking. It’s sobering. Not only have I reached the age where I’m no longer noticed as I walk by a building site, but the age where a person may well lead me by the elbow as I pass through a door, where my teenage daughter accuses my stomach of being a waterbed and where my youngest son strokes the lines next to my eyes with a sad and pitying, “mummy, oh mummy.”

I am now Family Hot Water Bottle, Unpaid Uber Driver, whipping post, protector, bank, chief negotiator, ancient mystery of a thing and rapidly sliding into the age of, dare I whisper it, Crone-dom. That insult of a word.

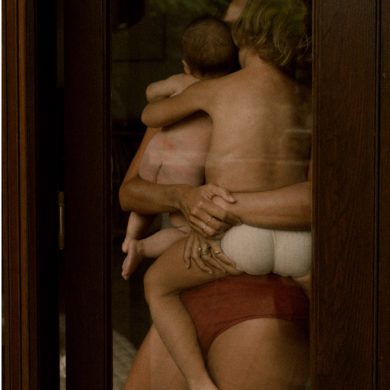

But now a major Australian gallery is celebrating exactly this: the older woman. The Crone. In all their beauty and complexity. And how often do we see females of a certain age platformed in our most prestigious art institutions? Rarely. But Hobart’s audacious Mona has just turned over a portion of its space to an exhibition called Crone, and it’s revelatory.

Tasmanian artist Sally Rees is on a mission to reinvent our idea of the word into something powerful, enchanting, earthed and wise. She transforms that ancient, ugly childhood moniker; that witchy, fairytale label that implies a back curled like a comma over walking sticks, a withering and a cackling. She shows that there’s muscularity in the word Crone, a lifetime of accumulated knowledge, a wildness and a hard-won strength.

Rees recently turned 50 and declared over a recent chinwag within Mona’s magical depths that “this (exhibition) is my alternative birthday party”. She has a strong, nurturing coterie of crone-women around her. In celebration, she chose to photograph 17 of them, all firmly entrenched in the so-called wilderness years. Their faces brim with story, with character and compassion and the richness of experience. There’s so much vivid living here.

Rees has created an otherwordly temple to the sacred feminine that has a cheeky, subversive, pagan energy to it. You enter a darkened Mona hall pockmarked with ghostly white video screens. The chosen crones float from their blank surfaces like pop videos from the eighties. Many of the woman wear beakish noses; a witty nod to the archetypal village crone who was dismissed and mocked and caricatured over the centuries. But not this lot. Oh no. This is reinvention. These women have found their voice.

One by one they make self-chosen bird calls, flooding the eerie space with fantastical sounds of the Australian bush. Some are melancholy, some joyous, some hesitant, some confident, speaking of inner pain and wonder, release and joy and lament. And Rees has literally painted the sounds; they emerge from the women’s lips in a burst of exquisite watery colour.

It is luminously beautiful. Provocative. Deeply moving. “They’re these fantastical, imaginary bird women,” Rees explains. “I wanted to break up the stereotypes of the older woman, show the diversity of this species.” The bird metaphor alludes to flight; to the freedom and sense of release beyond the childbearing years of relentless sexualisation and objectification. To the exhilaration that can lie in invisibility.

I wanted to break up the stereotypes of the older woman, show the diversity of this species.

Rees’s flock of birds are courageous and dignified and transcendently hopeful, especially for women on the cusp of the crone world themselves. “I’m so sick of looking at pictures of beautiful young women,” Reese says. “I look at these people (in my exhibition) as something to age towards. This is an opportunity to write the journey for yourself. These females are so smart, so quick and intelligent. We need to make sure women like this are valued.” And seen.

At a time when, as Rees points out, “there’s still a shortage of older women getting shown [in major galleries,]” Mona’s decision to turn over space to these post-menopausal creatures is heartening. “I would like people to feel they’re in a room of older women,” Rees concluded. “That they’re taking away with them a sense of females who are powerful and connected. It’s about wearing the accusation of ‘witch’ – and celebrating a network.”

I think of my own network as I look at these magnificent, barefaced females celebrating the subversiveness of their voices in their video-white oblongs. They remind me of the woman around me who nourish me. My coterie of joyous, blunt, vulnerable, hilarious females who are my circuit breaker from the grind of motherhood and wifedom. That world exhausts me, but time with my crone-mates never does. It uplifts me, energises me, gives me strength to plunge back into the family fray.

My coterie of joyous, blunt, vulnerable, hilarious females are my circuit breaker from the grind of motherhood and wifedom. That world exhausts me, but time with my crone-mates never does

I’ve chosen my women, carefully, as all crones do. As I age, I measure my friendships through the template of honesty. Why bother, if we can’t be truthful with each other? Why bother, if the world we present to others is a lie?

Real friendship is about being vulnerable with each other; about the difficult complexities of our lives, children, relationships. I’ve distilled my friendships – and the women that exhaust me, nibble away at my equilibrium, flatten with odd little barbs, I’ve moved away from. If I don’t feel like they’ve got my back, well then, what’s the point. There is beauty and connection in honesty, as Sally Rees well knows. And she celebrates it in this exhibition.

I’m not there yet, but my mates on the other side of the menopause tell me there’s a great freedom in slipping away from the exhaustion of that assessing male gaze. Picasso said that for him there are only two kinds of women, Goddesses and Doormats. But there is a third, one he perhaps never really saw: The Crone. And to me she’s the most interesting of the lot. Like Rees, I’m looking forward to this stage of my life with great optimism, as the magnificent crones around me blaze the way.

Picasso said that for him there are only two kinds of women, Goddesses and Doormats. But there is a third, one he perhaps never really saw: The Crone.

Yes, it feels like there are more eyelids than there used to be, the grey hairs are shooting most unbecomingly heavenward as if craning for the light, the eyebrows are growing ever more unruly, I have experienced the singular horror of a grey pubic hair (or two) and, indeed, dear daughter, the waterbed stomach is a given now, but I don’t see these as years of decline, at all.

They’re about burgeoning freedom and power. You see my speciality, once, was niceness, acquiesce, the big yes, until I was worn thin from it. Now I’ve found the release of saying “no,” to so much, and it’s exhilarating. I am no longer a doormat, imprisoned by trying to please, everyone, endlessly; am no longer cowed by what people think. I still buy Vans alongside the teenagers, still sneak a banana Paddle Pop now and then and still dance up a storm to James: “She only comes when she’s on top.”

It’s the same for all of my crone girls. There’s less angst among us about what we haven’t achieved in life; for many of us it’s a time to let go, graciously, and watch the younger shoots coming up strong. The intensity of the baby years has passed and we no longer feel shunted aside from our own lives. We’re reclaiming them. Re-finding those women we used to be, among women we want to be with. I feel stronger than I’ve ever been, more powerful, wild and connected to this beautiful earth, and alongside all that I’ve learnt to speak up loudly at a crowded bar. I have stepped into myself.

Sally Rees’s audacious exhibition celebrates all that. “Crone” is on until November. I urge you to see it. To revel in a great female artist at the height of her powers, who’s tipping a hat to ordinary, extraordinary, older Australian women. Women who’ve learnt that power in saying no. Who’ve embraced the bodily thickening. Who, at their most unvalued in the eyes of society, have been freed.

“One of the signs of passing youth is the birth of a sense of fellowship with other human beings as we take our place among them,” Virginia Woolf wrote. And dare I say a sense of fellowship with oneself. That strength is in all these crone’s faces. I suspect they’ve found a vast freedom on the other side of menopause, liberated from the gaze of men and released, finally, to be who they really want to be. Louder, more brazen, less careful. All Rees’s women have a strange, wild, witchy power. They’re not silent or invisible in their crone phase. They blaze with their beautifully honest voices. This is my future. Our future. Bring it on.

Crone at Hobart’s Mona, has just opened and concludes on November 1

For more stories like this, sign up to PRIMER’s weekly newsletter

No Comments