On the eve of Australia Day – as well as the 12th anniversary of the National Apology to the Stolen Generations – we spoke to three women whose families were impacted by the government’s forced removals policy, and who have dedicated their careers to making a difference for Aboriginal people.

“I became a lawyer to fight for social justice”

Merinda Dutton is a lawyer with Legal Aid NSW, who lives in Lismore. She is a Gumbaynggirr and Barkindji woman and her father was part of the Stolen Generations

“I decided to become a lawyer when I was in high school. That was when I started engaging with social justice issues, particularly around the Stolen Generations.

My dad was part of the Stolen Generations. He was taken as a baby and forcibly adopted into a white family. He had a very good upbringing and was well cared for and loved, but he was separated from his siblings. It wasn’t until he was an adult that he found his family, but his dad had died before he could make it back to him.

The older I get, the more I appreciate what Dad went through. He spent most of his twenties meeting his relations, including his siblings, and he grew up around people who didn’t look like him or understand his history or context. I think that must have been very lonely.

The older I get the more I appreciate what Dad went through

Today, part of my job involves helping people apply to the Stolen Generations reparations scheme, which serves as a regular reminder of my dad’s own experience.

When I meet [members of the Stolen Generations], I am always surprised by the extent of the trauma they have suffered. When people have been removed – and often abused after they have been removed – they spend their whole lives trying to deal with that. Often, they’ve never talked about what happened, even to their family, and when they come to see a lawyer, I’m the first person they’ve spoken to about it.

There is a high level of distrust for authorities among the Aboriginal community, but I think that being Aboriginal helps people trust me.”

“I was taken as a baby”

Audrey Silverton has worked in the domestic violence and sexual assault sector for 20 years. The Kaytidj woman was taken from her family when she was five.

I was about five when I was removed. I don’t have any memories of being taken, but my sister remembers chasing the truck [that drove our mum away]. She wanted to go with mum.

We lived in dormitories, with different house parents. Some were cruel, some were nice. I remember that when we were scared we would jump into bed with each other and when the staff came we’d get hidings. That kind of thing happened a lot. We’d get left outside in the dark or get a flogging with the hose as punishment.

It was a very military-like place. Growing up, we didn’t get emotional support. And then at 18, you’re sent away. You’re just dumped. And we just struggled, really, blindly through life after that.

One of the hardest things about being part of the Stolen Generations is the loss of family and identity. Before me, my mother was removed from her family, too, and I’m still trying to find family.

I’m still trying to find my family

I have six children, 18 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren. I wanted to create a family because the social welfare system destroyed mine. One of my granddaughters has a severe disability, and we’re trying to find out if it’s a genetic problem. But we don’t know because we don’t know who we are.

Come from a background of trauma, I have an understanding of where people are coming from [in my job]. There’s a sense of hopelessness. When people suffer from trauma, they might come in for one thing, but there might be six other things going on in their lives. There are often layers and layers of it. It’s about looking beyond what might be happening in that moment, and realising there could have been other circumstances including those that happened historically.

“I want to show other young people that they can do it”

Jasmin Onus is a lawyer who has worked in Indigenous land rights and policy. She is a Bindal and Gunditjmara woman who has studied at Harvard University. Her mother was the inaugural chairperson of The Healing Foundation

Growing up, it was rare to see Aboriginal people representing or advocating for our people, as lawyers or judges. A lot of the time, Aboriginal people were on the other side of the bench.

But I was raised to be passionate about social justice, and the experiences of my family and ancestors have definitely shaped my motivation to be in the law.

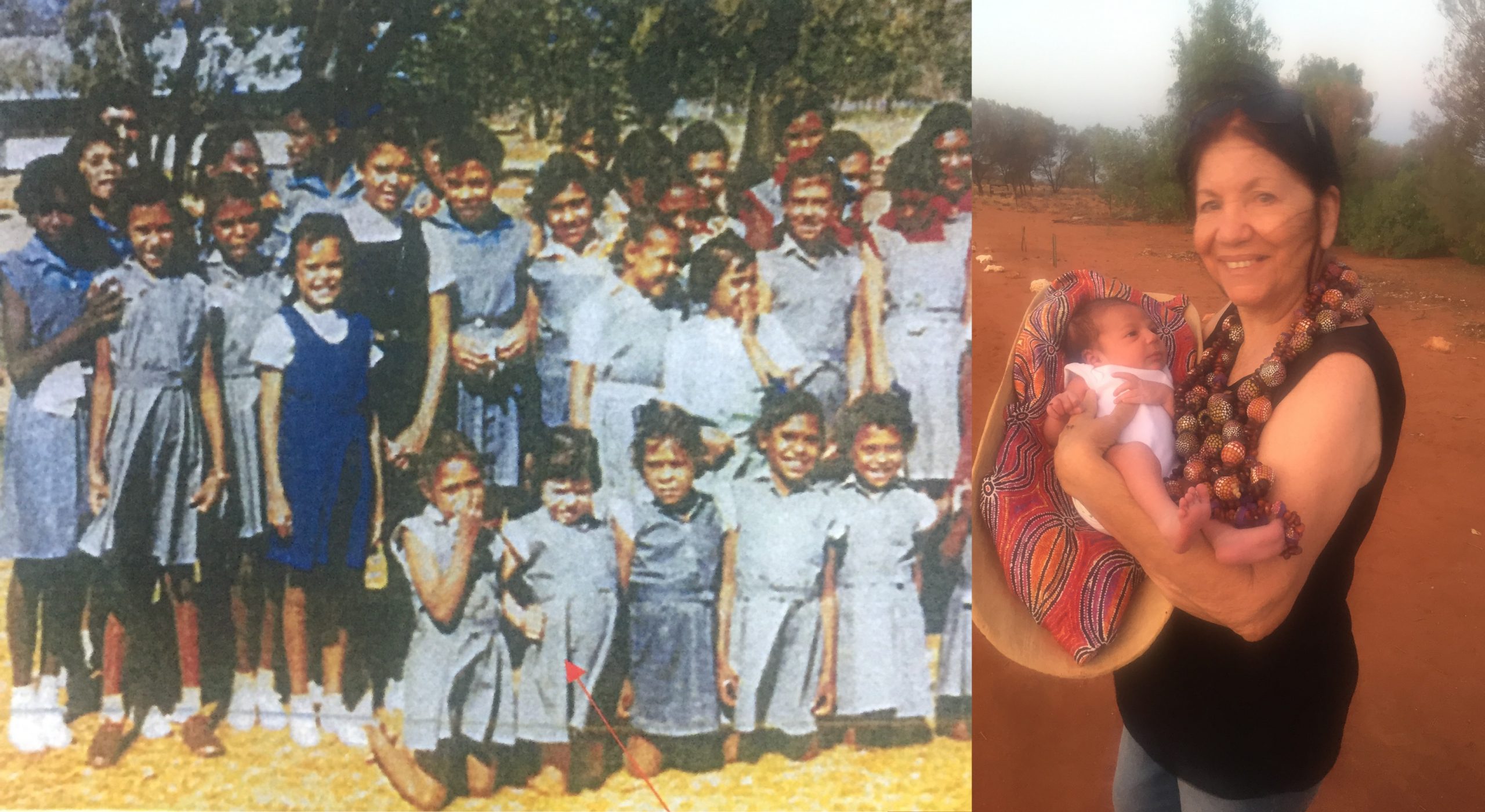

Three generations of women in my family were stolen, including my mum. She was taken when she was four, and placed in a home with a white foster mother and about 15 Aboriginal children. Most of her other siblings were dispersed across the country.

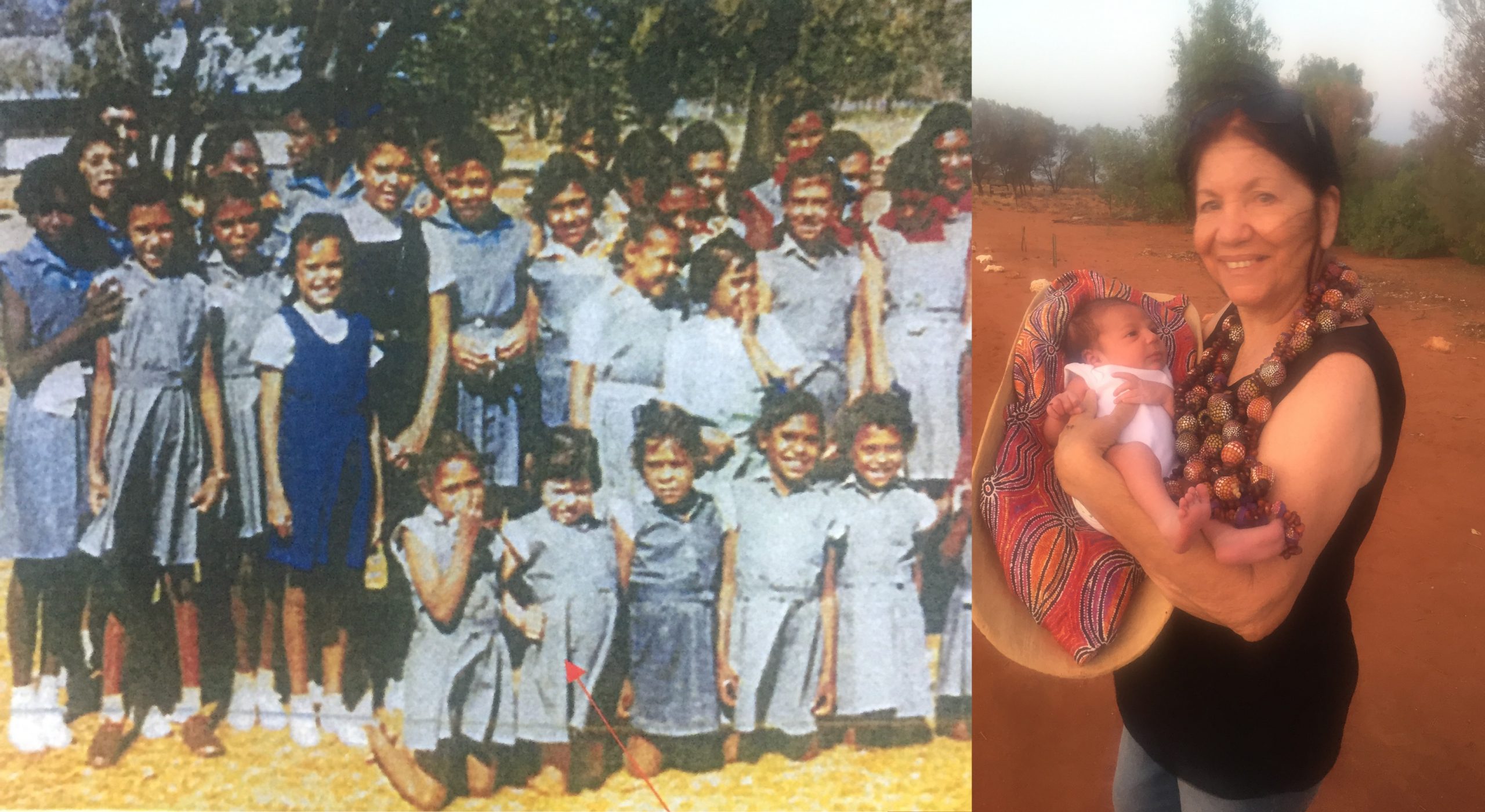

It seems almost unbelievable to me that my mother was ripped from her own mother’s arms at such a young age – especially now that I have a child of my own.

It seems almost unbelievable to me that my mother was ripped from her own mother’s arms at such a young age

And that trauma has a very real impact. One of my aunties passed away before she was even 50 because of all the trauma she suffered after being sent away interstate. Even my mother said she always worried that her children could one day be taken off her.

But I think it speaks to my mum’s resilience, and our people’s resilience, that despite what happened in our history – the dispossession, the displacement – she hasn’t let that define us as women.

I remember telling my mum in Grade 7 that I wanted to be a lawyer, and she said ‘You can do it’. But later, at school, the enthusiasm and support wasn’t already there and [teachers] would try and enrol me in other subjects. I want to show other young people even though my family was stolen, but I’ve been able to achieve.

When I was at university, people would always say, ‘You don’t have to be pigeon-holed and work in the Indigenous space’. But that is my passion: to support Aboriginal communities and to help our people achieve their aspirations.

No Comments