“Mama, this is to bring with you,” my six-year-old son Nathaniel said, handing me a bulky A4 envelope he had jammed full of who knows what and sticky-taped shut himself.

For the kids, he’d scrawled on the front.

I peeked inside. There were three apples.

It was mid-2016 and I was just about to leave for a trip to Yemen, where a horrendous war and bombing campaign by a Saudi Arabian-led coalition had created a massive humanitarian emergency.

The already-impoverished country of 28 million people was being slowly starved into submission by the Saudi coalition. Countless Yemeni children were dying from hunger as Saudi naval forces restricted entry of ships carrying food and flights into the country.

I wanted my two little boys to be aware of how lucky they were and appreciate that many others in the world were struggling, but I didn’t realise Nathaniel had heard me talking to my husband about the starving kids in Yemen. But he clearly had. I gave Nathaniel a huge hug and thanked him for thinking of them, promising to send photos to him and his brother as soon as I landed.

My Yemen trip was one of many assignments I undertook during my three years as the ABC’s Middle East Correspondent. I’d arrived in the region in 2015 with my family in tow. At thirty years old, this was my dream job and I felt so privileged to be there for the public broadcaster, based in Jerusalem and reporting from all over the region.

During my stint in the Middle East, I reported on a litany of wartimes throughout the region– hospitals bombed in Syria and Yemen, civilians targeted, chemical weapons attacks, food used as a weapon of war.

I became a journalist because I wanted to expose the truth, uncover the evidence of injustice around the world – inspire change and action to make the world a better place. But what difference did it make if the world just shrugged its soldiers and looked the other way?

I became a journalist because I wanted to inspire change and action to make the world a better place.

My trip to Yemen was one I was certain would have impact

When we finally secured visas, we had been trying to get into Yemen for months. Compared to the war Syria, Yemen was barely been in headlines, and I was desperate to get inside and document what was going on.

Earlier that year, a leaked UN report had outlined “widespread and systemic” targeting of civilians as the Saudis attempted to defeat Iranian-aligned rebels who had taken over the capital, Saana.

The detail was chilling. Civilians had been ‘chased and shot at by helicopters’. Refugee camps, schools, mosques and medical facilities had been targeted.

And although global leaders had – rightly – condemned the actions of the neighbouring, Syrian dictator Bashar Al Assad, the international community had been silent when it came to Yemen.

In 2015 Nobel Peace Prize-winning US President Barack Obama had even extended “logistical and intelligence support” to Saudi Arabia for their bombing campaigns – effectively offering them diplomatic cover, and allowing the US to make billions in weapons sales, too.

As we drove through Sanaa, we saw gaping holes where homes, public buildings and factories had once stood – all wiped out by airstrikes.

In a small town called Sanaban, we met 35-year-old Mohammad Jamal Al Sanabani who told us how a 500-pound bomb had been dropped on a family wedding nine months earlier. He recalled the moment – in the aftermath of the attack – that he realised his five-year-old daughter Jood was missing.

After more than 24 hours of frantic searching, volunteer rescuers approached Mohammad and his wife. ‘They said to me, “There are parts of a body, but the face cannot be recognised. Have you seen this hair clip before?”’ Mohammad said sadly.

‘Immediately we knew that it was our daughter Jood’s hair clip, and then we knew she was dead.”

All over Yemen, parents were burying their children, including those like Jood, whose last moments on this earth were filled with terror and fear.

And then there are those who have quietly slipped away, as tens of thousands of Yemen’s children starved to death as Saudi Arabia’s blockage on the country tightened.

All over Yemen, parents were burying their children,

Children like little Eissa, who I met in hospital and whose tiny body was so emaciated, it was difficult to tell how old he was. Skeletal and struggling to breathe, Eissa was so severely malnourished that his organs were beginning to shut down. There hadn’t been enough food at home, his parents told me sadly. I came back the next morning to see how he was but Eissa’s bed was empty. He had died overnight.

Our report on Yemen aired prime time on the ABC at 8pm on the Foreign Correspondent program.

But several months after our report aired, Defence Industry Minister Christopher Pyne travelled to the Saudi capital Riyadh to promote Australian military wares to senior regime figures.

And this is the part that continues to haunt me.

My greatest fear is that our collective indifference to the mass death, atrocities and war crimes in the Middle East over the past decade has sanctioned a broader unravelling of global order.

World leaders, those democratically elected and authoritarian dictators, now know exactly what they can get away with. We have proved ambivalent to their slaughter.

In the absence of any sufficient deterrence, they are now liberated from any pressure to rein in their murderous ways.

World leaders now know exactly what they can get away with

As a result, we are now paying an unimaginable price – a world with seemingly no rules and no truth, where disinformation thrives.

But we just cannot let this impunity continue.

Real change in this fight takes self-sacrifice. Unless we’re willing to sacrifice our time, energy and money to work together to make this world a more peaceful and liveable place, we must accept that not only will things not change, they’ll get worse. Today, the civil war in Yemen continues, and it’s estimated that 80 per cent of the population – 24 million people – need humanitarian assistance.

We can’t say we didn’t know.

The question now is, what are you going to do about it?

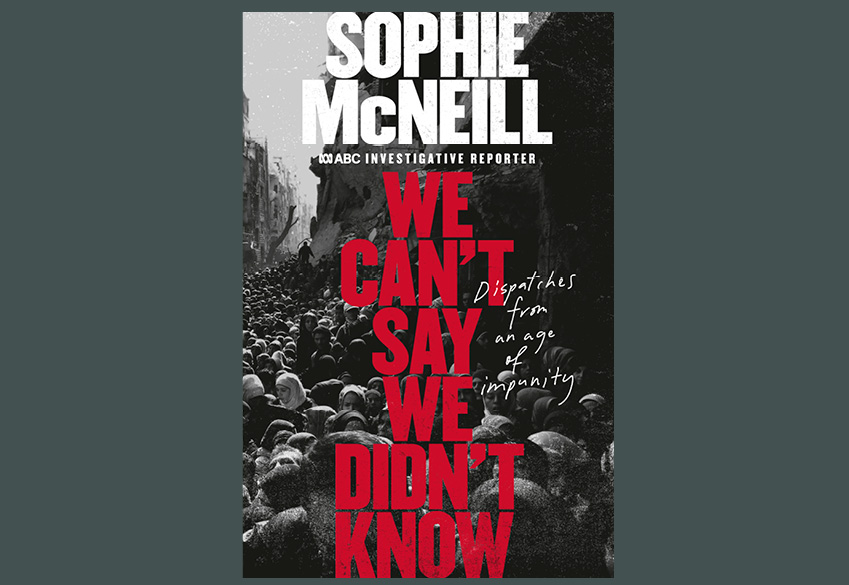

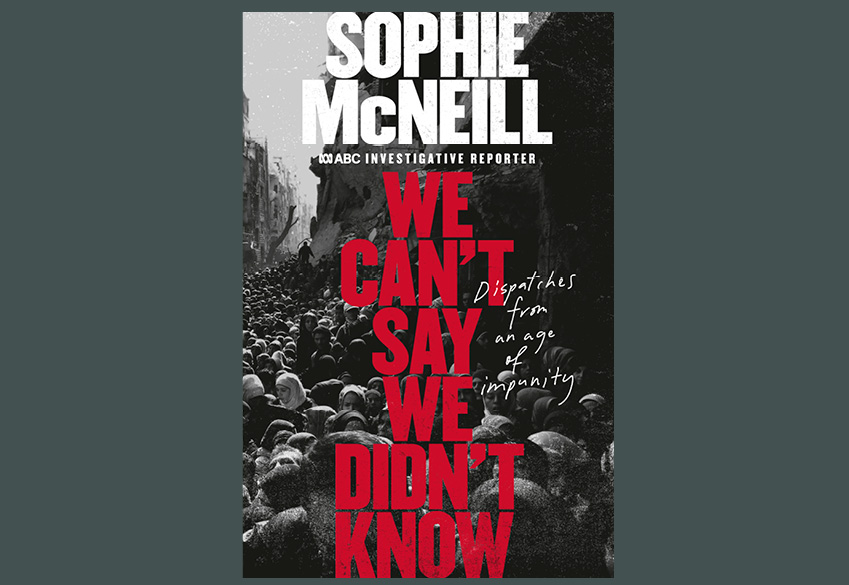

We Can’t Say We Didn’t Know by Sophie McNeill (ABC Books $34.99)

No Comments