Jacinda Ardern never wanted to be prime minister. She didn’t consider it until the possibility was only seven weeks away. It’s widely believed by political writers in New Zealand that everyone in parliament wants to be prime minister and if they say they don’t, they’re lying. But when Ardern said, over and over, that she didn’t want the top job, people believed her.

Not only did she not want to be prime minister, she appeared to not want a promotion either. From becoming a Labour candidate to the deputy leadership and then the leadership, Ardern was always asked to step up, often more than once before accepting. Apparently others wanted her to lead before she wanted to.

It would be tempting to label her a reluctant leader, but the swiftness with which Ardern adopted the role of prime minister, as if she were meant for the job, shows she wasn’t reluctant, she was simply waiting for the right time.

Ardern has succeeded where so many Labour politicians have failed. She did so by being a mirror. Embodying empathy, Ardern invited those she encountered to project their worries and struggles onto her, and in return she projected understanding and support.

Ask the average voter what Ardern did before becoming a Labour MP or what her greatest challenges were as a young person and very few would know the answer. Because Ardern’s personal experiences have never driven her political actions. Even as a teenager, Ardern acted on behalf of others rather than from self-interest. One does not run for student representative two years in a row for the social clout.

As a Mormon, Ardern didn’t want to wear shorts at school, but her schoolmates did – and she wanted to help them. Similarly, Ardern wasn’t a member of the LGBTQIA+ community fighting for equal rights in Wellington, but she saw they needed support and she gave it. She was so generous in that support that she became a well-known political ally to the community.

Ardern pushed for extended paid parental leave long before she had a child, in support of working mothers. Once she had her own, she took a bare minimum of six weeks. Politicians acting in the best interests of others, rather than themselves, should be the norm, but unfortunately it’s not. By doing so, Ardern has become a global icon of empathetic leadership, both a credit to her and an indictment on her international peers.

Ardern’s strength is her ability to speak on behalf of those without a voice. But in doing so, she has perhaps limited her ability to speak candidly for herself. At a time when it was almost a political asset to admit to smoking weed at some point in the past, Ardern could never quite bring herself to admit she had, saying instead when she was asked: ‘I was raised Mormon and then I was not Mormon – I let other people determine what that means.’

It was a clever answer, and made people laugh, but it was also typical of Ardern. She never reveals anything too personal, no matter how inconsequential. Or if she does, it’s artfully deployed. Those in favour of legalising cannabis could interpret her answer as being one of understanding and experience. Those against could read it as a roundabout way of saying she did it once a long time ago and never again. Everything and nothing.

Ardern has become a global icon of empathetic leadership

In many ways, Ardern is the perfect politician. Who better to represent the people than someone who puts aside personal views and works to fulfil the needs of others? The alternative is leaders like Trump or Johnson, who in governing are driven almost exclusively by self-interest. Yet even her supporters sometimes wonder: what do you actually want?

It’s hard to gauge. Even in personal, candid conversations, Ardern has an uncanny ability to shift focus. Having a conversation with the most famous person in the country is somehow never about the most famous person in the country. Getting a firm, tangible statement on what she wants can be infuriating because, as she’ll tell you, being prime minister is not about her, it’s about New Zealand. Which makes it all the more ironic that after a life spent deliberately promoting others’ stories and causes, Ardern herself has become the centre of the world’s attention.

****

Ardern’s government has made undeniable improvements. Extending paid parental leave, introducing free lunches for schoolkids in low socioeconomic areas, banning single-use plastic bags nationwide, small weekly payments for new parents.

These are all positive actions from a progressive government, but they’re not transformational. And those who voted for Ardern were promised transformation. Even the wellbeing budget was about improving, rather than changing. About heading in the right direction, not grabbing everyone and leaping there.

Even in personal, candid conversations, Ardern has an uncanny ability to shift focus

Ardern’s rhetoric has always been hopeful, optimistic and inspiring, but her political decisions lean more to the pragmatic. And in government she has learned, as many leaders on the left do, that it’s hard to remain a figure of inspiration within your own country when you’re in government.

Where Ardern has been transformative has been in her own personal, often instinctive, conduct. While the world watched as volatile men rose to power in some of the world’s most powerful nations, along came Ardern, a handbrake on the global identity car careening into the abyss.

New Zealand has always prided itself on being ahead of the curve, particularly with regards to women in politics. A prime minister giving birth while in office was largely accepted without a fuss. But overseas, in countries where women are still struggling for basic human rights, to see a woman have a baby while leading a country felt monumental.

Babies are now frequent guests in the debating chambers of New Zealand parliament, but the image of Arden, her daughter Neve and husband Gayford at the UN General Assembly marked a turning point in the global body’s approach to women in power. The simple act of wearing hijab in Christchurch united communities both in New Zealand and around the world after a terror attack. It sent a signal to leaders everywhere that even the smallest acts of kindness in positions of power make a difference.

New Zealanders believed terror would never find a home in their country and it did. In the days following the country tilting off its axis, Ardern held it steady. And in the same year, she would have to do it all over again after a volcanic eruption tragically killed twenty-one people at Whakaari / White Island off the east coast of the North Island. Regardless of anything else, the actions by Ardern in these two moments have cemented her in history. That she acted as she did in a global climate of conflict and vitriol cannot be forgotten.

In the second half of 2020, New Zealand will vote again for a leader. If the 2019 elections in Australia and the UK have taught the world anything, it’s that there’s no such thing as a predictable vote.

There are many kinds of leaders in the world. Some will go down in history as being only a force for evil. Others will be remembered for one or two things they did exceptionally well. Most will be forgotten entirely. Whatever unfolds, Jacinda Ardern will forever be known as the second world leader to give birth while in office, the first leader to take maternity leave from office, and the first mother to speak at the UN General Assembly with her child present. And she will be remembered for her humanity and empathy after the horrific Christchurch terror attack.

But Ardern wants her legacy to be more than being a working mother in office, or a ‘kind’ leader, and plans to make it so. Whatever she does, she’ll have the whole world watching.

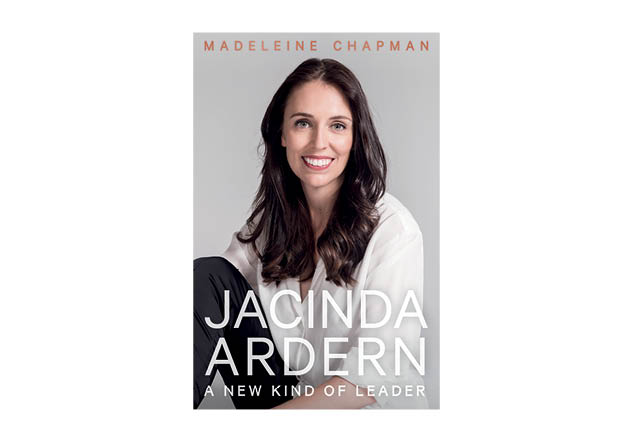

This is an edited extract from ‘Jacinda Ardern: A New Kind Of Leader’ by Madeleine Chapman (Black Inc.) Available in print and ebook. Visit blackincbooks.com or check out your local bookshop’s delivery options

No Comments