In the last few months we’ve all been forced to do a lot of waiting. Every day, we’ve waited to see if the curve has flattened, or if we can send children to school, or book a restaurant, or a holiday.

“We’ve been in a state of suspension, where we can’t take action or make plans,” says Professor Kate Sweeny, a psychologist whose Life Events Lab at the University of California is devoted to the study of waiting. “We’re used to being in those states for short periods of time, but the endless nature of this Covid-19 period is one of the reasons it’s particularly emotionally challenging.”

What makes waiting so painful is the uncertainty and lack of control, says Sweeny. Think of taking an exam, for example: in the run-up, you can harness your anxiety by studying. When you’re waiting for results, there is nothing you can do but wait impatiently for the outcome.

Well, there is something you can do. “What we’ve discovered is that in times of uncertainty, you should resist the lure of the couch and find an activity that enables you to reach a ‘flow state’, where you’re so absorbed in it that you lose a sense of time,” says Sweeny. “That might be playing an instrument, or gardening, or drawing – anything that takes you out of yourself. Another effective strategy is to find a sense of awe. So being out in nature, or even watching Planet Earth, tends to confer a sense of perspective that makes the self feel small.”

This week, we talked to three women who’ve had to wait for life-changing decisions about how they coped and what they’ve learned.

‘We’ve been taught we can control everything in our lives’

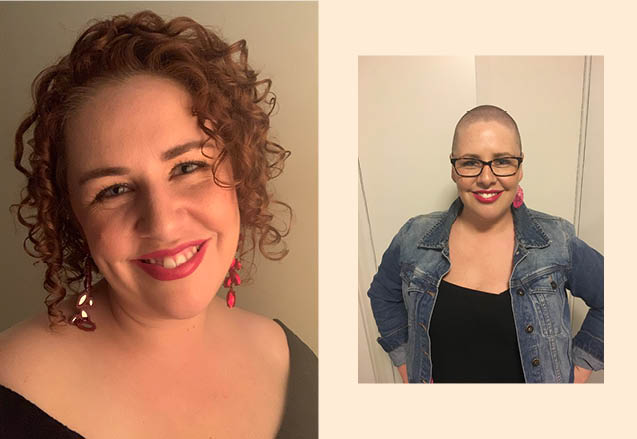

Despina Meris, a writer from Melbourne, endured several rounds of IVF and five miscarriages before her son, Evander, was born via surrogacy in Thailand

“The two-week period in IVF between the transfer of an embryo and the moment you can take a pregnancy test is difficult. No matter how many times you undergo it, the waiting doesn’t get any easier.

As soon as the transfer occurs, you start to over-analyse every twinge or cramp or passing moment of nausea for a clue about what the result will be. You watch what you eat and monitor your physical activity because you never want to give yourself the opportunity to say, ‘I made this cycle fail’. Then afterwards, you can feel that you did everything that was in your control.

You find yourself swinging between imagining that in two weeks’ time you’ll be pregnant, and thinking, ‘Let me just prepare for the worst.’ So during those periods I threw myself into work and socialising as a distraction.

At work, you can set targets and you can meet them; you feel that there are some things at least in your life you can control and achieve. You shouldn’t feel like you’re not being ‘successful’ at IVF, but you inevitably do. You lose perspective: IVF became so all-consuming that I felt if I didn’t have a child, I had nothing. So, it was important for me to become more attuned to other goals and cultivate my friendships to put things into perspective. My world wouldn’t be dark if I didn’t have a child; if it didn’t work out, there were other things to look forward to.

I don’t have a very controlling personality but I think in Western culture we’ve been taught we can control everything in our lives, including when we have children. It was very difficult for me to accept that I could do all the right things, and follow all the IVF instructions and it still might not work. It took years to reach that point of acceptance. Covid is a perfect example of the control delusion – we can have all the plans in the world, but we don’t really know what is going to happen.

The first time I held Evander was the largest, most incredible moment of my life, and so raw. I felt like I was experiencing every emotion at once, releasing this whole dam of feelings that I’d been holding back. Even through the pregnancy, I didn’t let myself celebrate at any point or take for granted that I was going to have a baby at the end of it.

We’ve been taught we can control everything in our lives

I felt vulnerable for a very long time. I still find myself feeling exceptionally grateful to have a child, but there is this constant reminder that you almost didn’t. While I was writing my book, I realised I had a lot of emotion and unresolved pain that I needed to work through.

Even if you do get the ending you wanted, it doesn’t negate everything you went through to get there.”

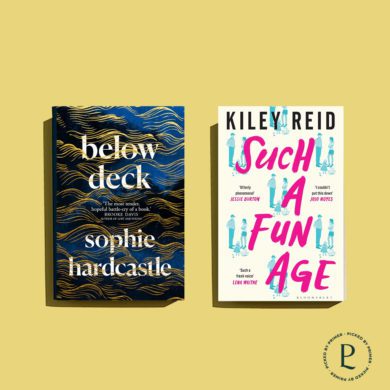

Every Conceivable Way by Despina Meris is published by Hardie Grant Books $34.99 and is available where all good books are sold

*********************

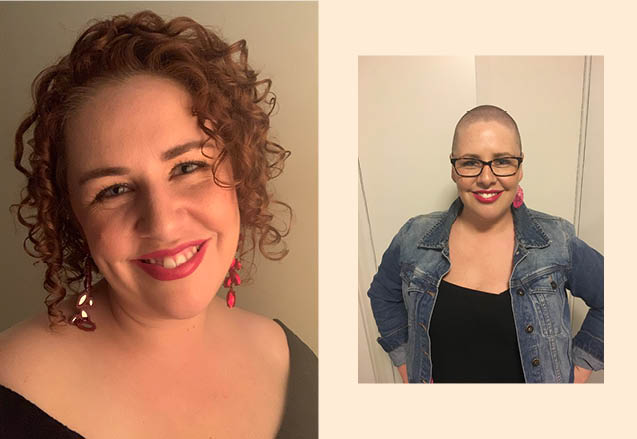

‘Turns out, faced with my own mortality, I organise stuff’

For a week in 2016, Anna Gilkison, 34, endured an agonising wait to see if she had terminal cancer

“In October 2016, I learned that I had cancer – a mass in my chest that was the size of a fist. It was devastating, but my haematologist suspected it was Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which is very treatable.

However, the cardio-thoracic surgeon I saw next delivered a very different opinion.

Bluntly, he told me he’d looked at the scans and didn’t think I had lymphoma. ‘I think it could be more serious,’ he said, as I sat at the appointment with my mum. ‘A different type of cancer. More often than not, it’s fatal.’

I was flabbergasted, floored. Waiting almost a week for the results of the biopsy to confirm his prediction was the worst, most horrible experience of my life.

I became intensely practical. I deleted my browser history. I planned my funeral and left a document on my computer detailing how I wanted to be remembered, and who my family should contact.

Turns out, in the face of my own mortality, I organise stuff.

My impatience was driving everything. I couldn’t be still, I couldn’t meditate or anything like that, because if I stopped I’d be overwhelmed. I had to be practical and busy and occupied.

I also ended up repairing a friendship in those few days. I had that cliched realisation that life is short, and I didn’t want to die not having this person as a friend. So I reached out to him, and it was funny because I was having a coffee with him when the surgeon called to say I had Hodgkin’s lymphoma – the ‘good’ cancer. I rang my mum, my friends – I was so excited. I would never have thought I’d be so delighted with a cancer diagnosis, but I had totally prepared myself for dying in six months’ time.

I became intensely practical

When I recall these memories now, I go back to my phone calendar and scroll through those cancer appointments, and think about that period. In the calendar, it looks like the smallest, most inconsequential amount of time, but living it felt endless.

Has the experience changed me fundamentally? Yes. It changed how I saw the world and how I wanted others to see me, and it changed the impact I wanted to make. I work in oncology now.

I’m not any better at waiting. But I do find myself taking deep breaths in traffic and thinking, ‘This is not important.’

*********************

‘I learnt acceptance’

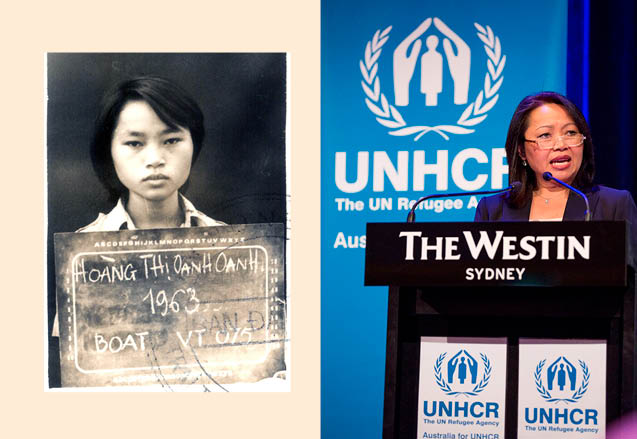

As a 16-year-old, Dr Carina Hoang spent 10 months in an Indonesian camp before being resettled in the US as a refugee. She is now a special representative to the UNHCR, an actor and advocate who lives in Perth

“When I was 12 and living in Vietnam, my father was arrested and we didn’t know for a long time if he was alive. It was my first experience of waiting for uncertain news. At first, we were so naïve; we children would get together each morning and whisper, ‘Maybe he’ll come home today.’

We imagined what it would be like for him to walk through the door, or for him to be waiting for us when we got home. But eventually those rituals died out. And four years later, I left Vietnam in a boat with my younger brother and sister, as my mum felt it was too dangerous for us to remain.

After landing in Indonesia, we were taken to what became a makeshift refugee camp on an uninhabited island. Other people from other boats arrived soon after – maybe a couple of thousand refugees, with nothing apart from the clothes on our backs and bare hands.

We were waiting for someone to help us. We had to hope, but every day we looked out from the beach towards the vast ocean, where we never saw a boat. There was never a plane in the sky. It was just us, the sky, the water and the jungle behind us.

I don’t think I could have survived if I was alone. Having my brother and sister meant having not only love, but someone to care for. I had a purpose to fight to survive. It was hard, but I tried to replace the negative images in my mind, and the possibility we might die, with positive thoughts of what it would be like to see my family again. Over 200 people died in the three months before the UNHCR and Red Cross found us.

I couldn’t have survived without my brother and sister

It was a different kind of waiting once we’d been interviewed by the UNHCR and accepted for resettlement in America as refugees. Initially, I felt relief and joy, but then I came back to reality. We didn’t know how long we would remain in the camp.

However, I felt more settled in my mind so I volunteered to work at the medical clinic, which was a tent on the beach. Keeping busy and having a routine saved me, really. This experience of waiting helped me learn to be calm and patient. And I learned acceptance, which is a difficult thing to accomplish.

If you accept what you can’t control, you don’t blame yourself for being incapable. And I now know that I am strong and compassionate. I understand human suffering, and I am resilient.

No Comments