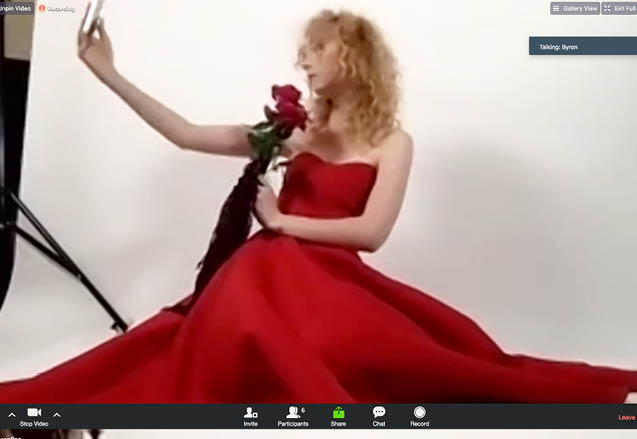

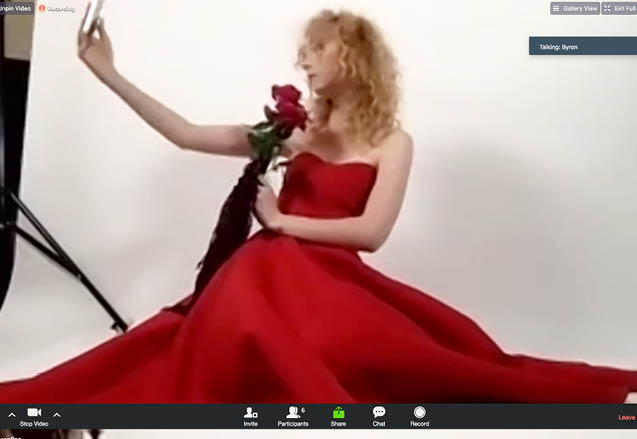

At her home in an Adelaide suburb, a young woman with porcelain skin and wide-set eyes spins around the lounge room in a strapless red dress. Her dad, Dean, looks on proudly from the sidelines. Occasionally, he jumps in to adjust a prop or snap a photo on his phone, but otherwise there’s no-one else here to witness this unique fashion moment.

No-one, that is, except the small team of creatives from Vogue Australia, who are masterminding the magazine’s first-ever remote fashion shoot through Zoom and FaceTime. The 23-year-old in the red dress is model Lily Nova, recently returned from London, and that red dress is pre-fall Christian Dior.

“The results of the shoot were fascinating,” says Vogue editor-in-chief Edwina McCann, who is running it across 16 pages in the magazine’s combined June/July issue. “Often, there are so many people on set for a shoot and so much stock – super-expensive jewellery, accompanied by security guards; models or actors with agents and publicists… that it can take away from that raw, creative experience. So to strip all that back was really interesting.”

For McCann, this shoot was just one of the many ways the magazine has responded to the challenges of the COVID-19 crisis, with a self-imposed ban on all shoots, even flat-lay, and photographers and other creatives producing work from their homes.

This is usually a busy time of year for fashion. Ordinarily, the Vogue team, along with fashion staff from rival magazines, would be preparing their schedules (and their outfits) for Mercedes-Benz Australian Fashion Week, which was due to start in Sydney on Sunday night.

Designers would be adding the finishing touches to their collections, international buyers would have arrived and hundreds of models, photographers, and hair and make-up artists would be poised to take part in one of the biggest industry events of the year.

Instead, thanks to coronavirus, fashion week has been cancelled, designers and retailers are struggling, and most fashion creatives are out of work.

And this week brought further bad news.

On Monday, just a few days after its merger with Pacific Magazines, Bauer Media announced a further 60 redundancies on top of the 70 already implemented.

The print editions of some of Australia’s biggest women’s titles – including Elle and Harper’s Bazaar – have been suspended, with rumours that other titles such as Women’s Health and InStyle have also been affected. (PRIMER has reached out to Bauer for confirmation and comment but hasn’t received a response.)

“It is tragic,” says McCann, who acknowledges that the closures and lay-offs mean there’s little competition in what was once a thriving category. “This is a really difficult time for the industry and it’s very sad that there are a lot of very talented people who are now out of work.”

Industry observers believe there will be many more redundancies and closures of fashion labels over the next few months, as the government starts to withdraw its JobKeeper stimulus and other benefits.

This is a really difficult time for the industry

Following a survey of its members, the Australian Fashion Council reported on Monday that only a third of respondents believed they would rebound financially from COVID-19. “The apparel and fashion industry is in crisis mode,” the Council said.

Yet while no-one (outside a select few scientists and soothsayers) could have foreseen the arrival of a pandemic, some fashion insiders believe the Australian industry has needed a correction for a long time. “I think it’s been broken for years and years,” says highly regarded Sydney publicist Adam Worling. “All we’ve ever done is put another pink dress on it and sent it down the runway.”

Worling points to the rise of the “celebrity designer” and collaborations with fast-fashion brands as part of the problem – “why did Erdem have to do something with H&M? Why did Karl Lagerfeld?” he asks incredulously – and says that for many brands, coronavirus will prove the final straw.

“There are some brands that will fall over. Those that will emerge from this stronger are those with cash flow and a good solid business that has invested in its customers.”

Some brands will fall over

Of course, cash flow is important to all businesses, but it’s more difficult to manage in a fast-moving industry that has such long lead times between production and sales. “Cash flow is such an issue,” says Lizzie Renkert, co-founder with her sister Georgie of Sydney-based label We Are Kindred. “The problem is that manufacturers demand 30 per cent of payment upfront, with the remaining percentage payable when the stock is delivered three months later. Then stockists – boutiques and department stores – have 60 to 90-day payment terms. So it can be at least six months before you see any return.”

So far, We Are Kindred hasn’t had any order cancellations, but other labels have reportedly found themselves in the unenviable situation of being left with inventory worth hundreds of thousands of dollars by department stores and boutiques who no longer want it. “If that had happened to us, we’d be out of business,” says Renkert.

Unfortunately, few labels will have the funds or the will to take on wholesalers, says McCann. “I think multi-brand retailers are going to be quite challenged [post-COVID-19]. I think a lot of designers here and overseas will be looking to take more control of their customer delivery chain. While they still need places for the discovery of their wares, they will be less inclined to rely again on those multi-brand retailers.”

Brands have been left with thousands of dollars-worth of inventory

Chains like Myer and David Jones have long faced difficulties – David Jones’ sales slumped nearly 20 per cent in March, following a 57 per cent fall in profits in the second half of last year. Overseas, department stores such as Neiman Marcus in the US have filed for bankruptcy.

With fewer people browsing in shopping centres, Dr Stephen Wigley, associate dean of Fashion Enterprise at RMIT, says department stores will need to think hard about how to provide an exciting customer experience.

“It’s not simply having lots of nice stuff in a shop,” he says. He points to US department store chain Nordstrom as an innovator, with its ‘Nordstrom Local’ concept – small, community-based spaces that let shoppers pick up same-day online orders and access a range of other services, like styling, alterations and manicures.

So what will the fashion industry look like a year from now? There will be fewer labels, says Worling: “It’ll be Darwinian, the survival of the fittest.” That’s not unusual for a recessionary economy, though; in the years following the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis, a slew of labels, including Kirrily Johnston, closed shop.

Those who do survive will need to be less reliant on China in terms of manufacturing, argues Matt Jordan, of MFPR, who tutors at The Fashion Institute in Sydney. “My sense is that those brands who had diversified their manufacturing capabilities pre-COVID are in a better position, because they’ve been able to deliver orders even as Chinese factories closed,” he says. “I think this has been a massive wake-up call for designers. It’s my dearest hope that more brands decide to manufacture here, but that requires long-term investment because we don’t have the capability or workforce right now.”

Local manufacturing is also more expensive, which means consumers will have to pay more for their clothes. Yet even before the current crisis, ethical manufacturing was becoming more important to consumers – a trend that has merely accelerated now, believes McCann. “We’re going to demand that our clothes are produced more sustainably,” she says. (Others aren’t so sure, at least initially. “Fast fashion is like an addiction,” states Wigley, “and it’s hard to break.”)

As for the annual extravaganza of Mercedes-Benz Australian Fashion Week, McCann predicts it’ll be back on a smaller scale. “I think you’ll see a return to something that looks more like the late 1990s, where the shows are much smaller and they really are more industry-focused, rather than being so influencer and celebrity-focused. We may also see a return to [designers] presenting collections, but only putting into production what has been pre-sold or generally popular.”

Above all, we’ll see a renewed emphasis on the provenance of our clothes and their quality. “I think we’ll be a little tempered and more appreciative of what we’ve got, and be willing to make do with fewer, but better-quality pieces,” says McCann.

And really, that’s it in a nutshell. Do we want to support local designers manufacturing here? Are we prepared to pay more for products that last longer? Ultimately, the future direction of the industry lies with us.

And what it’s like to run a fashion shoot over Zoom…

For Vogue fashion editor and market director Philippa Moroney, the biggest challenge of a remote shoot is planning the looks. “As a stylist I’m used to being able to feel the fabric, assessing how it moves and hangs – it’s a very tactile process,” she says. “So we set up a virtual fashion closet – at the home of our assistant, Rebecca Bonavia – and she described the pieces to us.”

Next, the completed looks were couriered from Sydney to Lily Nova’s home in Adelaide. “Casting was so important for this shoot, as we needed a model who could engage with the concept and knew her body and its angles really well. We knew Lily had that experience and creativity.”

Advised remotely by hair and make-up artist Gillian Campbell in Sydney, Nova prepped her own face and hair, while photographer Byron Spencer and Moroney directed the shots over Zoom and FaceTime. “Byron said he really had to calm usual energy levels,” Moroney laughs. “We’re all really pleased with the results – it feels like we’ve created a time capsule of the moment.”

For Vogue editor-in-chief Edwina McCann, the experience was a test-run for other shoots scheduled to take place overseas as lockdown continues. Thanks to Covid-19, her fashion director, Christine Centenera, has returned to Australia from New York with her partner Joel Edgerton. “If we’re shooting in New York or London, being able to have an art or fashion director on set through Zoom is now a very real possibility,” she adds.

It is also, as McCann observes, a way of reducing travel in an industry that has long been criticised for its environmental impact. “There’s no doubt fashion will be forever transformed by this [virus],” she continues. “There will be questions, and rightly so, about the volume of what’s created, sustainability and wastage.”

You can read more about Vogue’s shoot here.

No Comments