One night in 2013, Vanessa Russell was idly flicking around the internet when she decided to enter Ahmad Shah Abed’s name into Google. She hadn’t thought about him for years – and when she did, her conscience prickled with guilt.

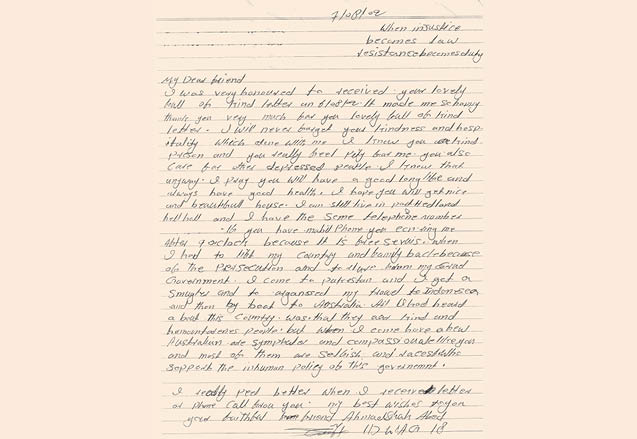

Ahmad Shah, then aged 24, had been an asylum seeker in Port Hedland detention centre, in Western Australia, when Vanessa started writing to him in early 2002. She was studying at the University of Melbourne, a well-meaning 28-year-old with a vague desire to do something to help refugees.

From the very start, their relationship felt uncomfortable, she says – Ahmad Shah with his pain and fear, and Vanessa with an ever-present sense of guilt and inadequacy.

“Even when I was writing to him, I felt I should be writing every day,” she says, of the letter-writing program she’d half-heartedly signed up to. “There was always that feeling that I should be doing more.” After two years of sporadic letters, as her own life became more complicated, Vanessa moved house and neglected to give Ahmad Shah her new address.

“I felt terrible guilt, and I knew I’d done the wrong thing, but I couldn’t give any more,” she writes. Vanessa never heard from him again.

There was always the feeling I should be doing more

Now, 11 years later, as she typed his name into the search engine, Vanessa imagined her erstwhile friend was living in Perth, maybe married with a family. The discomfort would have disappeared; instead, they’d laugh at the awkwardness of the letters they exchanged, and marvel at all that had happened in the intervening years.

But Ahmad Shah hadn’t had the chance to fulfil any of these imaginings. In 2009, he had been brutally murdered in his bedroom by his former housemate, Osman Ahmadyar, a fellow Afghan refugee he’d met in Port Hedland. There were a few news reports about the murder and Osman’s trial, and a Facebook post from a friend. But nothing else to mark the life of the man whose letters Vanessa still kept in a box in her room.

“I wanted to find out what happened,” she says. “I wanted to do more for him than I’d done during his life.”

This decision marked the start of a six-year search for answers that took Vanessa from Melbourne to Christmas Island, Port Hedland and Perth, where she came face-to-face with Osman, and found the courage to ask him directly about Ahmad Shah’s murder. She interviewed over 50 people, from friends and advocates to detention-centre guards, and wrote in snatched moments between her work as a teacher and caring for her young son.

Her book – The World Is Not Big Enough – is the culmination of these long years of research, recrimination and self-doubt.

“I worried that Ahmad’s murder fed into the prejudice of people who think all asylum seekers are criminals,” she says. Even Julian Burnside QC, the high-profile barrister and refugee advocate (“basically God,” says Vanessa), warned her for that reason against writing Ahmad Shah’s story, and suggested a more palatable story to tell. “He brought up some really valid points, and I had to talk to my editor and really work through them,” she says. “I didn’t want to do more harm than good.”

***

Yet Vanessa couldn’t let go of Ahmad Shah’s story. Painstakingly, she started to piece together his troubled, fractured life.

She learned that Ahmad Shah had grown up with his family in Gizab, a town in the central region of Afghanistan. In a prose poem published in an anthology, Another Country: Writers in Detention, he describes attending school for a few years before the Russians invaded in the 1980s and bombed his village.

“He remembered his mother crying as she put him in the basement,” writes Vanessa in her book.

When the Russians left, the mujahideen or ‘holy warriors’, took control, and the violence continued. Then came the Taliban, and during a battle, a rocket hit Ahmad Shah’s house, causing permanent damage to his left eye, and injuring his mother and brother. When the Taliban started to round up young men of Ahmad Shah’s age to fight, his family decided he should leave.

He travelled alone to Pakistan, then Indonesia, and set off for Australia in a boat organised by people smugglers. Picked up by the navy on Ashmore Reef, he was briefly processed at Christmas Island – where he, like other arrivals, was given an identification number – before being transferred to Port Hedland.

It was a place he referred to in his letters as a “hellhole” and a “human zoo”.

By the time Vanessa visited Port Hedland in November 2017, the detention centre had been closed for 13 years but the Tetris-like buildings remained, abandoned to the dust from nearby mines and the searing heat. The scars of what happened there – asylum seekers sewing their lips together in protest at their incarceration, riots and beatings, and tear gas – lingered, as Vanessa discovered in her interviews with former inmates and staff.

One retired religious chaplain, Bev Fabb, told her of a children’s party one Christmas, when Mission Australia had managed to get presents for each of the 120 children in the centre. All the children were dressed in their absolute best clothes, she said, and when Santa arrived he started to call them forward to collect their gifts.

To Bev’s horror, they were called by their identification number, rather than by their names. “It was one of the most dehumanising things I had ever seen,” she told Vanessa.

Many refugees became suicidal; Vanessa spoke to a former nurse who suffered PTSD as a result of her experience at the centre.

After spending nearly four years in Port Hedland, Ahmad Shah, too, attempted suicide, and in 2004 he was transferred to a psychiatric hospital. By then, he and Vanessa had lost touch.

Vanessa admits that there were moments in her research when she had to take a break from piecing together her friend’s story. “That’s why it took so long,” she says, in her softly spoken and sometimes hesitant way. “I picked it up when I could and if it was getting too much, I would put it back down again.”

As a subject for biography, Ahmad Shah also proved as elusive – and often infuriating – as he had when Vanessa wrote to him. In the book, she describes her frustration as he criticised her poor handwriting, asked constantly for CDs and books (“I invariably sent the wrong ones”), and later made “weird” declarations of love.

“He’d ask for stuff; I’d get annoyed and would passively aggressively not write back for a while,” she writes. “Then when I wrote back and sent the stuff, he’d very apologetically ask for something else, then I’d take a while to reply. It really makes me hate myself. But how to do you tell someone in detention to back off? He was asking more than I was capable of giving.”

Vanessa’s depiction of herself throughout the book is brutally honest. “There are so many places where I could have just made myself seem a bit of a hero,” she laughs. “But it’s not true.”

He was asking more than I was capable of giving

Similarly, she felt her dealings with Osman, Ahmad Shah’s murderer, were “morally dubious”.

Initially adamant that she would never speak to him, Vanessa started to exchange phone calls and then Skype calls with Osman at his prison, an hour out of Perth. At one point, she helped Osman access his bank account, even though she suspected it might be money he’d stolen from the man he’d murdered. “I’m a natural problem solver,” she says, with apology in her voice. “I don’t know, I think I wanted to help, I wanted to please, I wanted to get the book done.

“In many ways he was the ideal interviewee,” she continues. “He’d answer anything I asked him – he didn’t baulk at any question. I didn’t like him, but I didn’t dislike him either.”

After Ahmad Shah had been released from hospital on a bridging visa, he stayed in a Christian community in Perth for a while, before finding an apartment with friends. He was working as a fly-in-fly-out worker at the mines, saving money and starting to build a life for himself.

For a while, Osman Aymadyar, was sleeping on Ahmad Shah’s sofa, drinking heavily and smoking marijuana. After his release from Port Hedland, he had spent time in prison for sexual assault, and his mental health – due in part to the horrors he too had witnessed in Afghanistan – was deteriorating. In August 2008, after trying to help him reduce his alcohol intake, Ahmad Shah demanded that Osman move out – and took an AVO against him once he’d left.

Six months later, on February 12, 2009, Osman broke into Ahmad’s apartment and overpowered him, binding his hands and feet together so he was helpless. Over the next three hours, Osman tortured and then murdered Ahmad Shah with a kitchen knife.

There was no single motive for the murder, writes Vanessa. “There was a furious mixture of inadequacies, shame, jealousy… a feeling of entitlement. Trauma and shame. Shame, shame, shame.”

***

Port Hedland may have closed but Australia is still keeping asylum seekers in indefinite detention. A Sri Lankan family with two young children has just spent their third Christmas on Christmas Island after their plea for asylum was refused. “I’d love people to read the book and gain more of an understanding of what actually happens to people,” says Vanessa. “It’s written through my eyes, just a regular Australian. Maybe they’ll be able to see some of themselves [in that].”

For Vanessa, the book’s publication has delivered a feeling of closure. “When I stopped writing to Ahmad Shah I had a sense that I’d left something unfinished, that it was hanging over me,” she says. “I felt I’d left him hanging. But I was having a hard time in my life and I did what I could with the resources I had. I’ve learned to forgive myself.”

The World Is Not Big Enough by Vanessa Russell is out now (Hardie Grant)

No Comments