The first thing you need to know is that the camera always lies. Light the subject from above, and cheekbones emerge from the face. Add a softbox, and the years slide away. Shift a reflector and the world moves with it. The ultimate lesson is that the most powerful force is light.

I remember the exact moment I realised I was fat. It was Christmas. I was 12. I was standing in my grandmother’s spare room, the lace curtains filtering the sunlight into soft licks. I remember the pants distinctly: a pair of pale-blue and white short trousers, fitted at the thighs. They were patterned with flowers, a pastel Eden.

As I passed the mirror, I saw a stranger. The body I had looked at my whole life had shifted in a single moment of monstrous clarity. The thighs strained the seams of the floral pants. The stomach was distended and bloated. Only the face I recognised as mine. I had the sensation of expanding uncontrollably, fat bubbling under my skin, flooding my clothes.

As a child, I had checked the mirror to admire my surfaces: outfits and expressions. I had never given much thought to what lay underneath. In this room smelling of powder, I looked at myself for the first time with an adult gaze. I looked at my body and used a word I had never used for it before and, in doing so, I was altered irrevocably. Words are weapons. As I called myself fat, I went to war.

Over the next four years, the weight dropped, etc etc. Plateaued, etc etc. I doubled down, etc etc. You know this story. You’ve heard it before. Like a stock image, it is too familiar. You’ve heard it too many times. The details shift slightly. Only the endings are different.

I came out of it like someone waking from a deep sleep, like rising through dark water. At 16, I had been sent home again by the school nurse. I cannot remember her face, just the light through the doorway to her office, on the edge of a courtyard filled with roses. My mother made me lunch for the first time in years. I sat at the kitchen table eating a mug of packet soup and a sandwich. It was more food than I’d eaten in one sitting in a long time.

There was a strange and unfamiliar feeling. It started as a spark in my chest and trickled outwards. I felt life spread through me, the nourishment warm in my bones. It felt as though I’d cleaned my glasses: the world crisp and solid and real. I realised, quietly and stupidly, cow-like, daft, that food made you feel good. That the brittle, toffee-like fragility of existence was softened by eating. In that moment, I stepped from one life into another.

I came out of it like someone waking from a deep sleep

My memories of the years after bloom with bright, saturated colour. In my 20s, I revealed to a female friend my starved little secret. I was expecting hushed words, shock, pity. Instead, she nodded. ‘So, basically, you were a teenage girl?’

At university, my newfound freedom expanded my social circle and my dress size simultaneously. Now, I rolled through a world with no limits. After years of bodily punishment, I discovered the hedonistic thrills of bodily pleasure. I gorged on sex and food with the fervour of the starved. My heart was wild with feeling. It grew along with my thighs. I watched my body’s progress with curiosity and fear. I knew how to starve it, and I was learning how to swell it, but I had never learnt how to care for it.

I found other avenues for my discipline. When I first picked up a camera, in my first semester of university, I took a self- portrait every day for a year. At 18, I learnt how to light, how to edit, how to expose and how to hide. I was my own most patient and devoted model.

Taking control of my image

Across that year, I put on weight, but to look at the images, you’d think the opposite was true. I took control over the visual narrative of my life. I learnt the trickery of it, how to tell the camera what to notice. How to elevate the tripod so that a shadow fell hard under my chin. How to tilt my head slightly to the right to make my eyes seem bigger and my jawline sharper. How to smile viably, charmingly into the cold eye of the lens.

I built a portfolio of myself online. To those in the digital no-space of the virtual realm, I was unfailingly creative, flirtatious, effortless. Men twice my age messaged me, confessing that their wives didn’t satisfy them, asking if I’d consider flying interstate to meet. I was sexy in the images in a way I had never been in life. I had lost the capacity to control my body in the real world, but I could control how it represented me online.

In my second year at uni, I began to photograph other people. Fellow students and actors, full of excitement at the prospect of modelling. Full of their own anxieties and insecurities, too. It was one thing to make tweaks to the reality of my own body; it was another thing entirely to make those decisions for other people.

The requests started almost immediately, little throwaways: ‘Fix it in post [production],’ and ‘Shoot from above so you can’t see my chins,’ and ‘Photoshop me til I’m unrecognisable.’ Jokes that didn’t feel much like jokes. Now and then, someone would ask if I’d do a nude shoot with them, to help them feel good about their bodies. I said yes, a few times, at the start: photographed women who lay in lingerie and told me how much they hated themselves, who begged me to make them sexy. One woman, a friend of a friend, posed nude apart from her favourite pair of high heels. When I showed her the photos on the back of the camera, something retreated deep inside her. She became monosyllabic. She drew her knees towards her chest. When I sent her the photos, she never replied. I don’t say yes anymore.

Body as brand

On social media, brands act like people and people act like brands. We become our own products. It serves us to present the tidiest content. I have a note on my invoices, asking clients not to put Instagram filters over the photos I send them. Now and then, someone does it anyway. My hours of work tinkering with colour and tone fall away, crushed into contrasty oblivion.

The filters that people habitually choose all share certain characteristics. They desaturate skin tones. They flatten highlights and crunch shadows. They turn faces into textureless, blank surfaces. There are no lines, no freckles, no creases. Just clean, flat skin. I wince at the wasted effort. I understand it, though. It is arrogance that makes me think that only I have the right to sculpt their images.

Body positive

Recently, a shift began to occur in my Instagram feed. In the photos, stomachs bulged over bikini bottoms and cellulite dappled the skin of thighs. Fat bodies stepped into the spotlight, smiling, calling for body positivity, for loving the self as it is, not what it could become. The posts made reference to an approach called Health at Every Size (HAES), which encourages movement and intuitive eating instead of calorie control. HAES marks success with positive behavioural shifts rather than pushing for weight loss. Friends I knew and influencers I followed praised the approach, its revolutionary notion that all bodies are deserving of love and respect.

I became oddly fretful. I sat on Google late into the night, reading articles about whether an overweight body could in fact be a fit one. These articles terrified me. For a decade, I had put my hope in some grand future moment when I would finally get my shit together and Get Healthy. In reading these posts, I found a strange new fear: that I was already there. That I was already caring for my body, even while it was unwieldy and large. That being thin was not the marker of good health. That I would have to accept an imperfect thing.

On social media, brands act like people and people act like brands

For a time, my partner Mike drew a daily three-panel comic as a form of diary-keeping. I took great pleasure in his scribbled drawings of me, my mop hair and round glasses sketched out across the page.

We had been to the beach one day. I had waded into the freezing ocean in my underwear while he stood laughing in the shallows. As my feet went numb, I had looked down and sighed at the scale of myself. When I thumbed through Mike’s notebook the next day, he had drawn that moment. In the sketch, I am reaching up to brush the hair out of my eyes, encircled in foam. There are lines radiating from my head, and a heart floating above me. The caption reads: ‘She looked so beautiful coming out of the water it made my heart explode.’ For a week, I picked up the notebook whenever I passed, and stared at the panel. I stared at it the way I’ve had clients stare at the back of my camera, with the wonder of seeing the self transfigured into something new.

The camera lies, and so do the eyes. There is no truth, only versions upon versions. The body shimmers at the edges of vision, waiting to be coalesced.

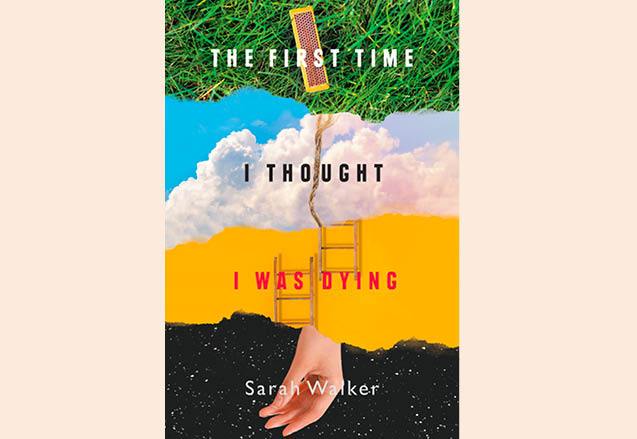

The First Time I Thought I Was Dying by Sarah Walker (UQP, $29.99) is out on August 3

No Comments