Dear Dad,

You lived a textured life. One full of colour and movement. A life dedicated to family, friends and your brothers in arms in the Army. A life largely without sickness, except towards the end. You were incredibly healthy.

The last time I spoke to you it was late in the night, or at least it seemed late. At moments like that one, time slows down. Memories seemed so fleeting; patches and flashes of emotion crashed into my thoughts when least expected, least convenient. Probably like the way I used to storm into your room as a toddler, while you were resting after a long week on the road for work.

The conversation was brief, it had to be. You could barely breathe. ‘I’m not in pain, Dan, I’m just… it’s frustrating,’ you husked down the line.

We were trying to organise for Ethan and Hayley to see their Pop one last time. It was Monday night; they couldn’t get to you in Echuca until Wednesday. ‘Wednesdee?’ I could hear you doing the sums in your head, like you were calculating how many jerry cans you would need to make it to Horsham, and what time you would need to hit the road. Except this time, you were figuring out whether you’d still be around to tell them how much you loved them. You knew then you’d run out of breath.

Although you all loved each other, you needed to say it, and they needed to hear it. Neither eventuated. You were gone early the next morning. The sky was so red that morning, sailor’s warning.

You were the first generation off the mission, one step removed from the collective memory of your Elders; one of the many of your mob who were trying to make their way through the cracks in society where opportunity sometimes bloomed, like dandelions in a footpath. For you, that dandelion was the Army. An army that went to Vietnam.

You never told us what it was like to be a Blak man in a racist organisation during a racist time, where you were a pariah in an army of pariahs. Perhaps your silence was a result of the opposition to the war itself. Maybe you thought the details would be boring to us kids. Maybe what you lived through was far too painful to recount.

It was a photo that gave me a glimpse into your pain. Adorning the fridge for many years was a platoon intake photo. Among other boys, expected to be men, was 21-year-old you. The commanding officer’s face was scribbled out with pen so violently it left a hole in the photo. I never asked you about it, I didn’t have to.

The commanding officer’s face was scribbled out with a pen

When you passed away, I was affected in ways I never expected. I suddenly felt alone in the world. After a Tigers’ win or loss, usually a loss, I felt like the phone was broken. Surely you’d ring.

One of life’s oddities, of course, is that I am far from alone in experiencing that sense of abandonment. Almost everyone who loses a parent feels this way. Every loss is unique. Every episode of grief is its own expensive cocktail of memories, sorrow, anger and hurt. No two are the same. That’s why grief is important, it has to play its own course, there’s so much to let out, to let go. Writing this letter is part of that process.

Maybe you could’ve written to Nanny James as I am writing to you. You suffered badly when we lost her. Your grief played itself out in a myriad of ways over the rest of your life. Some too personal for me to write about here. I like to think I was there for you in those moments, but I wasn’t. Mum had left, us kids had grown up and gone. I’m sorry you went through those times alone.

I wonder if your greatest companion was the road. You worked on the road as a Telecom linesman for decades. You lived the largest part of your life moving along the flanks of the Hume Highway. Between Wangaratta, Benalla and Euroa for forty-five of your sixty-five years. Up and down you went, as a driver, a passenger, and in your younger days, as a hitchhiker. You walked your Country, made your own songlines, despite them never being handed down to you.

There wasn’t enough money to send me to school camps, so one year it was decided I would go on the road with you to work for the week. I was disappointed not to go on camp, of course. I only ever went on one camp during my whole time at school. I knew I was missing out. Going away and spending 24 hours a day with your school mates built a new type of connection. Now I look back on it, I can see that the opportunity to go away with you for that week was probably the best week of my childhood.

You showed me the back country around Omeo, about as remote as you can get in Victoria. Your wisecracking sense of humour was on full display, a trait I seem to have inherited. You were kind, you were generous, and you were my hero. You still are.

I often think about the searing summer temperatures in the Commission house we lived in in Benalla. We were lucky the cool waters of Broken River, so refreshing at dusk, we were only a short walk away. Those waters mended everyone’s frayed edges.

You wouldn’t have known this, Dad, but Benalla or Benwhalla (Big Water), as the local Waveroo people called it, was a meeting place for at least three tribes, the Bangerang, Taungurong and the Waveroo. You may have seen the plaque in Mair Street alluding to it being a scared site or some such to the local Aboriginal people. But that’s as close as you would have got to any anthropological lesson about your forbears.

What chance did you have to learn about the traditional way of life, when those who could have told you were wiped out at least three generations before you were born?

You were kind, you were generous, and you were my hero. You still are

You inherited the traditions of the modern Koori: street smarts and a willingness to fight. You ended up in the lock-up so many times during your formative years, I find it amazing you never went to prison. You said people thought you had a chip on your shoulder, I think it was the other way around. The tension, the atmosphere of some of those small towns back then that would fill you with anxiety – the racism. We know who had those chips.

Living in a small town, a sheep farming community famous for Wool Week, soon after the High Court’s Mabo decision that ended the fiction of terra nullius, was tough for us Koori mob down south. The racism we copped in the pubs, streets, football grounds and at school was aggravated by the truth being found in the highest court in Australia. The dogs were off their chains.

Your example during those times, your principled stance in the face of overwhelming opposition and ignorance, was perhaps the greatest life lesson you bestowed on me. Yet you never lost your sense of humour.

Here’s that extract from the Euroa Gazette circa 1993, when you made it to the news at the height of Mabo and the Native Title debate.

MABO – MAYBE

There was a real verbal stoush at the entrance gate before our last home match against Mooroopna.

The very popular Billy James – who is always willing to remind friends that he is very proud of his Aboriginal heritage – refused to pay his five bucks. Billy claimed it was a sacred site – and the land belonged to him anyway.

The resultant conversation can’t be recorded in your family newspaper. To cut a long story short Billy finally paid – under sufferance.

We learnt a lot about each other in your last years. I say last years and not latter years because the ages from 62 to 65 don’t seem particularly late to me; they seem too early.

By the time I came back to spend time with you, you were the last Blackfulla in town. You had got your final tattoo by then, a small Koori flag across your chest. Somehow the sun was off centre, probably because your heart was so big that it had its own centre of gravity.

The racism we copped was aggravated by the truth being found in the highest court in Australia

By this stage of your life and of our relationship, there was no longer any sugar coating of aspects of your history and the way you were feeling about the world and your place in it. There were truths told that were once untold. Feelings expressed that had once been repressed. And a quiet realisation there was more to look back on than to look forward to.

At home in your last years, you would sit staring across the corrugated-iron rooftop of your neighbour’s home, watching the tall ghost gum changing colour and form in the afternoon light. It was mesmerising, the last of its ghostly glow disappearing at dusk.

I wonder how many of your thoughts, feelings and regrets are caught in that majestic tree’s foliage, fed from the waters of Seven Creeks nearby. If I think of a physical and spiritual manifestation of you now, it is that tree, by that creek.

It’s the way these things happen.

You quietly told me once, ‘It takes 10 years to get over the death of a parent.’ If that’s the case, it’s going to be a long three years.

Love

Daniel

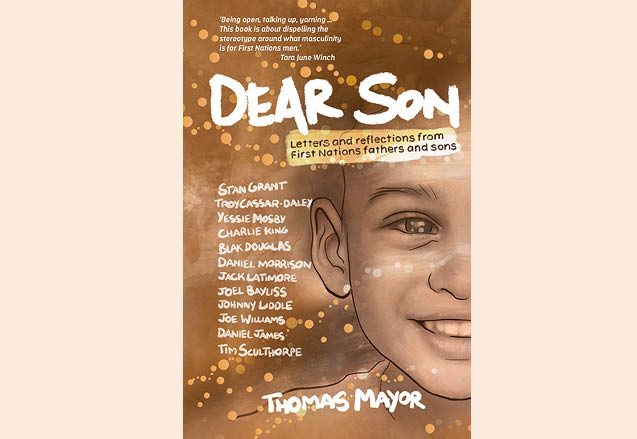

This is an edited extract from Dear Son edited by Thomas Mayor and published by Hardie Grant Explore

No Comments