I was a typical young girl in many ways. I enjoyed the literary works of Ann M. Martin and Francine Pascal. I had an extensive collection of stuffed animals, and I made sure to distribute their sleeping-in-the-bed rights evenly so as not to hurt any of their feelings. I liked twirling. And like most young girls raised on a diet of boyfriend stories and people-pleasing, I assumed that one day I would be married.

It wasn’t a question of ‘if ’ but of ‘when’. I wasted little energy worrying about the chap involved, presuming he would arrive just as the seasons did: indistinguishably at first, and then all of a sudden there.

A committed fan of movies like Working Girl and Don’t Tell Mom The Babysitter’s Dead, the visions I had of my future life more often than not involved me working as an ambitious secretary or conning my way into the inner circle of a fashion house and then bluffing my way out of a mess of my own making. There would be men, of course, but they would be a by-product of the real storyline of my life, which would feature adventure, independence and a fake identity, and not necessarily in that order.

There would be men, of course, but they would be a by-product of the real storyline of my life

Still, the matter of a husband at some point seemed inevitable. [And] after the torrid years of my twenties, with the series of broken hearts that decade brought (mostly mine, sometimes other people’s), I met the man who would become my son’s father.

We’d been living together for three years when I informed him of my desire to have a child. I was thirty-four and had just signed a deal to write my first book. It seemed as if all the work I had put in during the gruelling slog of my late twenties and early thirties was finally paying off, so what better time to throw a wild bull into the proverbial china shop and add sleepless nights and a broken body to the mix?

Of course, I didn’t know about the reality of newborns then.

Nor was I prepared for how destructive those little creatures can be to relationships. The genteel life I imagined for myself was cast in soft, pastel focus.

I would finally be a published author. I’d have a placid, chubby little baby who cooed at all the right times and cried only when absolutely necessary, which would be never. And I’d have a loving partner who supported me emotionally in both of these endeavours, understanding without question or conflict what needed to be done and simply getting on with it.

Things, as they say, didn’t quite go according to plan.

My pregnancy was plagued by chronic anxiety, none of which was helped by the fact I was also on deadline for the book.

He was absent for much of it, producing an album for a friend’s band that was consuming all of his time and challenging his perfectionism.

I felt like I had become the single stakeholder in a massive project we had started together, and the feeling only escalated once our son was born.

I felt like I had become the single stakeholder in a massive project we had started together,

The birth was traumatic, both physically and emotionally, and our adjustment to this new reality came as an even bigger shock.

I resented the ease with which he seemed able to return to life as he knew it, as if nothing of consequence had really occurred.

The days were long and lonely, and with a baby who wouldn’t sleep unless connected directly to my body, they were also often suffocating. In the pre-dawn hours, after another night of broken sleep and relentless feeding, I’d look at the man lying asleep next to me, the one I’d fallen in love with over golden sunsets and buttered rums and think, I hate you.

One of the things I had always valued about our relationship was how independent we could be of each other—which is to say, I had valued how independent I could be.

I was often travelling for work, sometimes announcing it at a moment’s notice. I was still playing roller derby, a sport that required a lot of time out for training and an almost equal amount of time for socialising.

I am an introvert by nature, and the emotional toll of being so busy also means I have to recharge in solitude. When it was just the two of us, it was an ideal situation. But the introduction of a third, defenceless creature to our situation upended all of this.

For the first time in my life, I needed help. I needed respite. I needed to feel supported in some fairly basic ways. And like so many women stunned by the reality of the ‘happy ever after’, I felt myself to be abandoned.

For the first time in my life, I needed help. I needed respite. I needed to feel supported in some fairly basic ways.

I experienced the shock of motherhood and its impact on our relationship as a huge betrayal, and I blamed him for most of it. My book, a feminist manifesto and memoir, had been released when our son was seven weeks old. I had a public reputation for being a ‘man-hater’ whose feminist wrath had made her the scourge of trolls everywhere.

For years, I’d been telling women not to tolerate sexism from men. How could someone like me have been caught in the terrible trap of domestic drudgery, while a man skated alongside her with very little disruption to his life or any awareness of the labour that went into facilitating it?

I wasn’t just angry and hurt about the new reality of my life. I was embarrassed.

But I was also in the grip of the early childhood years, when it takes all of your energy just to keep treading water. So I persevered, trying to keep us all afloat even though it seemed I was carrying the world on my shoulders. And it took so much out of me that, in the end, I had no energy left to keep from drifting away on the current until he became nothing but a speck in the distance.

We had been breaking up for a long time when I finally said the words out loud to him, but the moment I did I was flooded with relief. I took no pleasure in hurting him, but I had been hurting myself. My desires were modest, but they were important. I wanted to stop feeling sad. I wanted to start feeling happy.

In the months before I decided to leave my relationship, I found myself thinking about what I wanted my life to look like. Did I want to wake up at fifty and realise that I had no idea who I even was anymore beyond being someone’s mother or someone’s wife?

I didn’t feel seen, and the knowledge left me with a deep wound.

Outside of my home, I was championed and celebrated. My work made a difference to the lives of girls and women, and because of this I felt confident to use my voice to speak up against injustice. I was achieving a level of notoriety in my career that was both flattering and professionally fulfilling. Yet despite this, when I laid my head down at night I felt invisible.

I couldn’t understand why this man who claimed to love me didn’t also seem to notice that I was disappearing.

On an afternoon in late May, I piled the last of my things into my car and drove away from the house I had shared with a man I had once loved.

I did not cry as I drove away, just as I had not cried as I listened to him ask me again, Why? Why are you doing this?

[In fact] I hadn’t cried much over the break-up, save for a few mournful tears here and there for what might have been, what could have been preserved, if if if.

But by then my heart had sealed over. I had watched myself moving slowly out of the relationship long before I moved out of the house, but he, like so many people seemingly blindsided by the end, had not noticed.

I drove to my new flat, and I looked at the new home that I had made and I wondered at all the possibilities left to me. Some of them would be mundane, but others would be thrilling. There would be love, I knew that. There would be laughter. There would be magic. My heart would slowly heal, and the cuts, the beautiful cuts that remained, would leave space now to let new light in.

There’s a dish I often made while living at the old house. One of the central ingredients is mushrooms, but I had always left them out because the man I lived with didn’t like mushrooms.

I had tried so hard, as we all do, as even he did, to take care with the tiny details. To smooth the path for the people I love to try to make their lives a little bit easier.

Shortly after moving into my new flat, I sat down to eat that same dish. Outside, it was cold and dark. June. As was my habit, I had left the mushrooms out, and I didn’t realise it until halfway through the meal.

Next time, I thought to myself, I’ll add the mushrooms. I can do that now, I thought. That is a thing that I can do.

I love living alone.

I love having my own space. I love that the things in my house are my things, that the mess is my mess. I love that the clothes that sometimes find their way onto the floor are my clothes, and that the only person responsible for picking them up is me. I love that I can come and go as I please on the days of the week when my son is with his father. I love that the time I have with my son now is untainted by domestic resentments and exhaustion.

I wonder if I have always been meant to live this way and simply lacked the role models to show that it was possible.

I imagine a world in which our entire notion of ‘family’ is reinvented. Where women’s desire for motherhood is divested from our belief that it can only happen if we enter into a nuclear partnership.

I feel as if I have the best of both worlds now. I am a mother, and this brings to my life a particular meaning and resonance that is important to me.

But I am also a woman outside of this, and I don’t need to struggle to remember this fact. I move easily between the two states of being, without the risk of one consuming the other.

From the ruins of our relationship, the American and I have emerged stronger.

I love the time the three of us spend together as a family. I love watching how the relationship of father and son has bloomed since I extracted myself from the centre of it.

We eat together frequently, going to our local pub for cheeseburgers and pinball. This is where the man and I have the kind of conversations we used to have, our son drawing next to us or running around the beer garden with other children.

On other days, we might take him to the park. We’ve started having movie nights, showing him the classics of our own childhood or discovering new ones together.

It took a long time to get to this point.

But time is a great healer of wounds, particularly when one makes the decision to treat them with care. We will live like this forever, I think. He’s family, and always will be. I have chosen well.

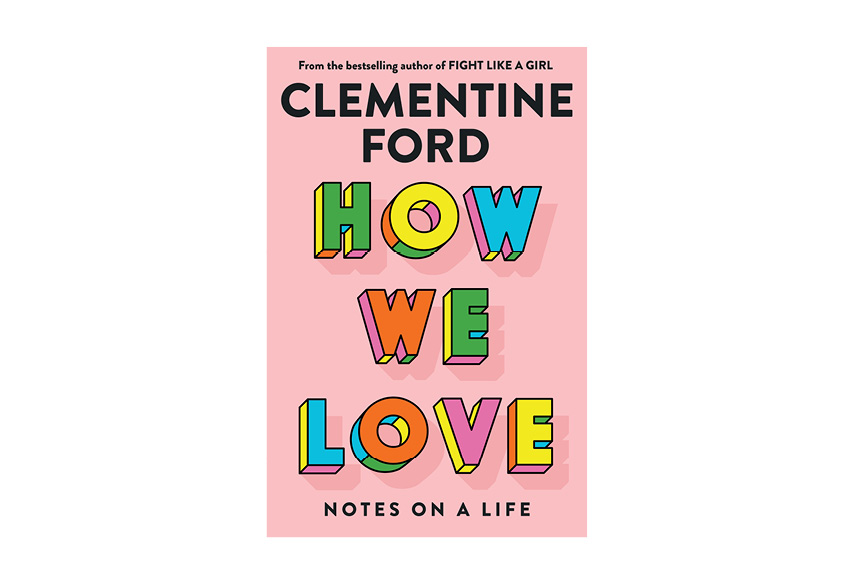

How we love – Notes on a Life (Allen & Unwin) by Clementine Ford is available for pre-order now and is on sale from November 2.

7 Comments