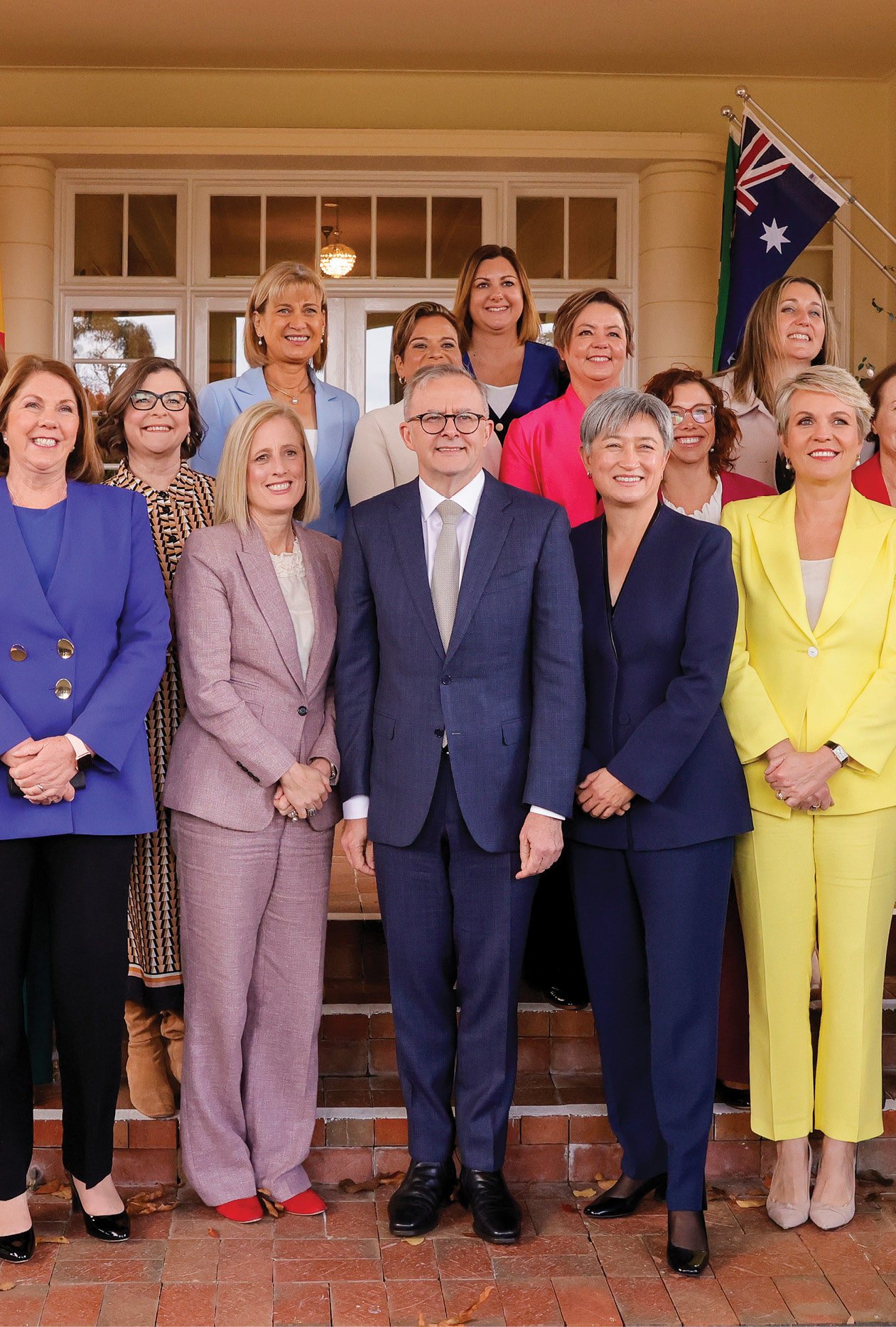

When the new Prime Minister Anthony Albanese stood up in front of the Labor Party caucus for the very first time since winning the election, he quoted former Prime Minister Paul Keating: “When you change the government, you change the country”.

But he might have offered a slightly revised version of that famous quote that’s a bit more fitting for the times we’re living in: “When you change the face of the government, you change the country”.

When the 47th parliament sits for the first time in July, it will be the most diverse on record. In the House of Representatives, there will be more non-European MPs, thanks to the addition of Sally Sitou, Michelle Ananda-Rajah, Sam Lim, Zaneta Mascarenhas, Cassandra Fernando and Dai Le. And over in the Senate, Fatima Payman, the Muslim daughter of an Afghan refugee, picked up a spot.

Indigenous representation has also increased, with the addition of Marion Scrymgour, Gordon Reid, and Jacinta Price. They join Labor’s Malarndirri McCarthy, who was re-elected, and Linda Burney, who has become the first female Aboriginal minister for Indigenous affairs.

At this stage, the House of Representatives will have at least 58 women, making 38 per cent of the chamber female. That’s the highest proportion of women ever in the lower house. The percentage of women in the Senate will remain at 50 per cent.

That’s the highest proportion of women ever in the lower house.

This means that – for the first time – Australia has well exceeded what’s known as “critical mass”, which is the theory that women are not likely to have a major impact on legislative outcomes until they grow from a few token individuals into a considerable minority of all legislators.

When their numbers increase to more than 30 percent, so the theory goes, women are able to work more effectively to promote women-friendly policy change and to influence their male colleagues to accept and approve legislation promoting women’s concerns.

If you wanted to point to one thing that shows the magnitude of the immediate impact, it’s this: the influx of women has vastly improved Australia’s 20-year backwards slide in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap ranking of women in national parliaments – a trend that Sonia Palmieri, a gender policy fellow at Australia National University, describes as “mortifying”.

The influx of women has vastly improved Australia’s 20-year backwards slide in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap ranking of women in national parliaments.

The new-look Parliament means that Australia has moved up from 57th place to around 37th in the rankings.

“If you think about the fact that Australia was a pioneer for so long in terms of granting women the vote, granting women the right to stand for election, the fact that Australia has for 20 years been sliding down while so many other countries have been shooting up the rankings and making women in parliament an issue, taking action, this is a recognition that we needed to do better,” says Palmieri.

And so we have.

What’s more, after Kate Jenkins’ Set the Standard report on the culture of Parliament House came out last year – a report commissioned in the wake of former political staffer Brittany Higgins’s sexual assault allegations – a number of Jenkins’ recommendations focused on the need to change the culture of Parliament by making Parliament more diverse and gender equal.

“This answers women’s call to be better represented — and responds to all the anger, the calls for ‘justice’ and the feeling that there was something that needed to be done,” says Professor Michelle Ryan, director of the Global Institute of Women’s Leadership (GIWL) in Canberra.

“It’s a signal to the women of Australia that something is changing, that they’re being heard, that representation is important, and that they can look up and see people who look like them and who will, hopefully, represent their interests.

It’s a signal to the women of Australia that something is changing, that they’re being heard.

But will the change be more than symbolic? Will it really affect policy and legislation? That remains to be seen, but there’s solid evidence it will make a difference.

A recent report from the GIWL and the Westminster Foundation for Democracy analysed more than 500 pieces of research into the impacts of women leaders around the world and found that having women in politics plays a key role in creating a political system that delivers on issues that create a more equal and caring society.

On average, according to the GIWL report, women politicians work harder than men to accurately represent their constituents, which is linked to a stronger sense among voters that the government is responsive to their needs. And the increased representation of women helps to counteract corruption in politics, while countries that have more women in office are less likely to go to war and less likely to commit human rights abuses.

Here in Australia, the results of the election – and the new, sizeable crossbench made up of so-called “Teal” independents, Greens and other independents, the majority of whom are women – is a particularly interesting development, and it has put both major political parties on notice that voters want, and expect, politics to be done differently.

“That’s an interesting phenomenon, having those women on the crossbench,” says Ryan. “Hopefully they will hold the major parties to account; this election should give both major parties pause to think about why the crossbench — and the Teals and the Greens — were so popular.”

There are also promising signs the 47th parliament will be more family-friendly than those of the past. Natasha Stott Despoja, who famously entered Parliament at just 26 representing South Australia in the Senate for the Democrats – the youngest woman in Australian history to do so – has talked openly about the impact of having her first child in 2004.

“I think I realised very early on (after becoming a mum) that the combination of travel, as well as long hours, was going to make it difficult. There were no childcare facilities on site… When I saw that [new] childcare centre at Parliament House… I shed a little tear, because it would have changed my life,” Despoja has said.

At his first press conference after being sworn in, Albanese explained he planned to run a family-friendly Parliament and indicated he would take care to avoid school holidays when scheduling sitting weeks, among other things.

Andrew Giles, the new Minister for Multicultural Affairs has been frequently sighted (yes, by me) at the school pick-up, so in the equal parenting stakes, there’s also reason to believe that this Parliament will have a number of men who don’t just talk the talk, but walk the walk.

The scenes of ministers – both men and women – carrying their young children into Parliament House for the swearing in of the new ministry, with the children subsequently running through the halls of power with their childlike, reckless abandon, was heartwarming and greeted as such on social media.

The scenes of ministers – both men and women – carrying their young children into Parliament House was heartwarming.

Finally, when there’s more women in political leadership roles, that changes the perception of women in leadership more broadly, and that’s a good thing, says Palmieri. It changes the norms of leadership (what does a “good” leader look like).

“This election, unlike others, has proven that women are not electoral liabilities,” says Palmieri. “They are winners; they won more of their seats that they contested than men. That is a really important lesson for us.”

No Comments