On 28 March 2020, the Facebook Messenger app on my phone pinged with a message from Mum. Forwarded from whoever had sent it to her, the message laid out some “important information about the new coronavirus”.

‘The virus hates heat. Therefore, hot drinks such as infusions, broths or simply hot water should be consumed abundantly during the day. Avoid drinking ice water or drinks with ice cubes.’

It went on: ‘For those who can, sunbathe. The Sun’s [sic] UV rays kill the virus and the vitamin D is good for you.’

According to the poorly punctuated, copy-pasted screed, the advice was originally sent as an internal email to staff at the Royal Brisbane Hospital. ‘Please share with family, friends and work colleagues,’ it implored.

My mother diligently forwarded a second, abridged version of the same message, a moment after the first. It claimed to be ‘SERIOUSLY EXCELLENT ADVICE by Japanese doctors treating COVID-19 patients’.

It claimed to be ‘SERIOUSLY EXCELLENT ADVICE by Japanese doctors’.

It was obvious that neither claim was true and, to me at least, that the advice was nonsense. “Unfortunately this is total BS,” I replied. “Happy to talk – have spent last few days talking to experts on transmission.’

Hot water won’t stop the virus, I told her. Washing your hands is a good idea, I said. And facemasks make a difference, I added, even though not everyone was convinced of that at the time.

A couple of days later, Mum sent links to sewing patterns for facemasks, no doubt discovered on the same platform she’d found the other dubious messages.

Despite reporting on little else, I barely spoke of the pandemic with my mum over the next year or more. My world contracted around me. Lockdowns, home-schooling, and interviews about contact tracing, facemasks and specks of contagion carried on air currents dominated my days.

—

But in August 2021, Canberra was on the precipice of lockdown – a first for my mother – when my brother texted me. ‘So, I’m kind of worried about [Mum]. She’s gone [off] the deep end with covid conspiracies,’ he wrote. ‘Anti-lockdown, anti-vaccine … all the right-wing loopy stuff from the states,’ he wrote.

His main concern was for his kids – aged eleven and nine at the time – who were being fed a diet of fearful warnings from their grandmother. Microsoft founder Bill Gates is bankrolling vaccine development, she told them, and they’re not really vaccines at all, because they alter your DNA.

I was aghast. But I wasn’t surprised. For as long as I can remember, my mum has held unconventional views.

For as long as I can remember, my mum has held unconventional views.

Mine was a homebirth. On a frosty Canberra morning, I slid into the world in the bedroom of a suburban weatherboard, midwife in attendance, oxygen tank at the ready.

I received no childhood vaccines until I attended high school, and I was wholly unfamiliar with the idea of a family doctor. Mum was an acupuncturist and Chinese herbalist long before she qualified as a psychologist. And on repeated occasions she has demonstrated what I eventually saw as her credulous side – buying into cult-like religious groups and get-rich-quick schemes that inevitably failed or, more often than not, left her worse off than before.

I’d rarely challenged my mother on her beliefs. Perhaps out of cowardice, perhaps because of a sense that such efforts would be futile

I’m far from alone in having a significant personal relationship catastrophically rupture over questions of how the pandemic has been managed, and over the COVID-19 vaccines, in particular.

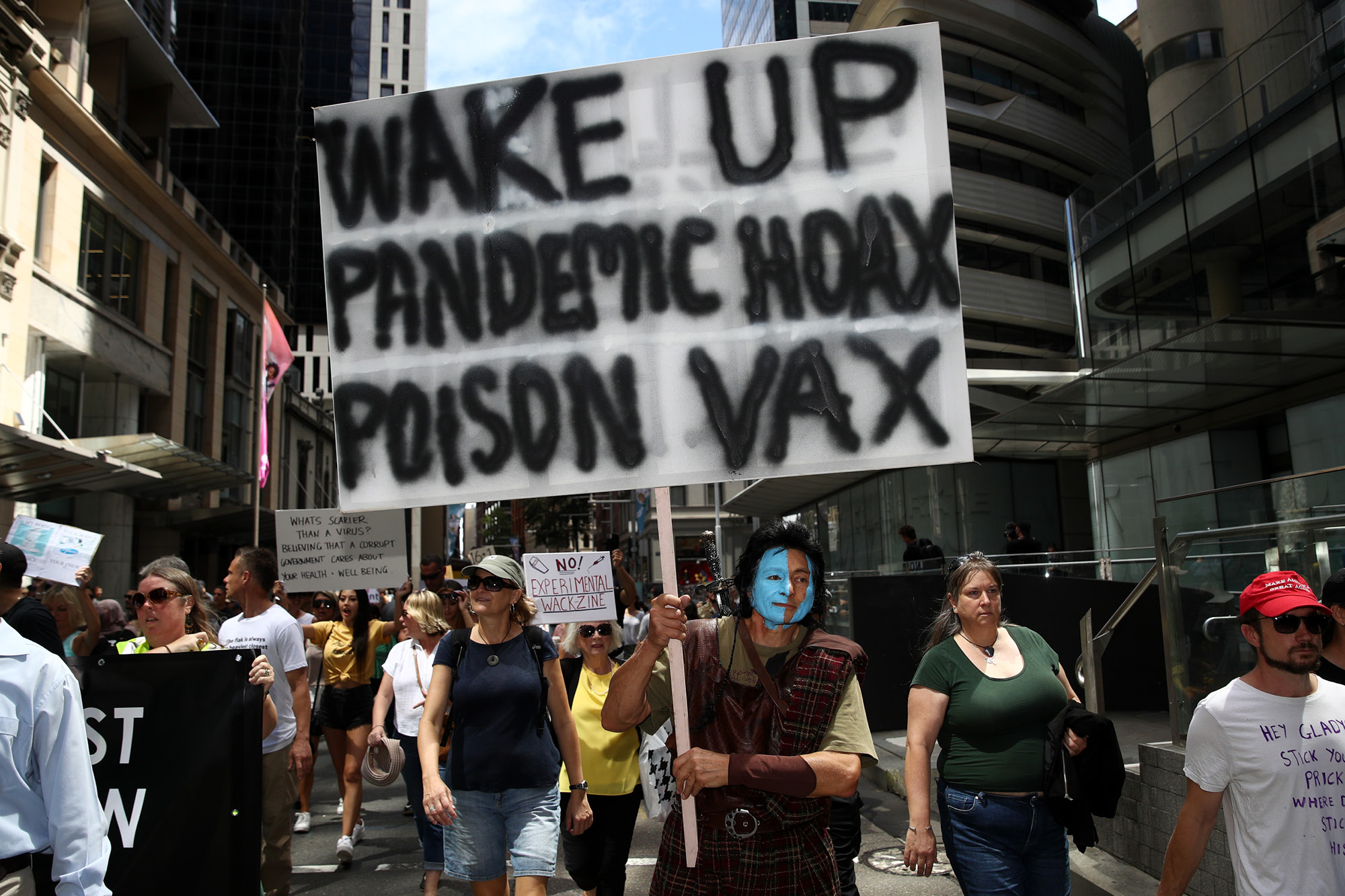

Ask anyone, and they will tell you of a person in their orbit – a family friend, a brother-in-law, a colleague at work – who has chosen not to be vaccinated, lost their job because of vaccine mandates, or joined one of the many ‘freedom’ rallies to decry restrictions that have been placed on the unvaxxed.

Despite their seeming ubiquity, all the experts I spoke to for my book Unvaxxed (psychologists, social scientists, epidemiologists and others) told me that true anti-vaxxers – not the fearful, or the hesitant, or the time-poor, or the complacent, but the people who would stake their reputations and livelihoods on refusing to be vaccinated – are actually rare.

By winter 2022, upwards of 95 per cent of eligible Australians had been vaccinated against COVID-19, many of them having received three doses of one COVID vaccine, or a mix of different COVID vaccines.

When I spoke to Julie Leask, a social scientist who is the go-to expert on vaccine refusal, I asked her about the best way to combat anti-vaccine activists. Her advice: don’t give them oxygen.

I’ve wrestled with this conundrum. But I believe we need to take an unflinching look at why people who could access vaccines if they wanted to are instead refusing them, despite overwhelming support for vaccines from all corners of the scientific community and regulatory machinery.

The great unvaxxed are painted as selfish free-riders, relying on the goodwill and compliance of the rest of the community so that they can shirk their communal responsibilities. But what are their motivations for refusing vaccination?

Who are the refuseniks?

At the heart of vaccine refusal – and the more virulent anti-vax activist movements – is a deep-seated sense of mistrust. The lower the trust in authorities, the less likely someone is to take a risk – such as the risk of a vaccine side effect.

In addition, says Matthew Hornsey, a social psychologist at the University of Queensland who studies why people reject scientific ideas, when there’s competing information, some people fall back onto a mental shortcut. They rely not on the word of experts but their own gut feelings and instinct, fuelled and coloured by fears, superstitions and personal bias.

In 2016, Hornsey and his colleagues surveyed more than 5000 people across 24 nations to identify the roots of the anti-vaccination attitudes. What shocked Hornsey most was that – more than any other factor measured – anti-vaccination attitudes were accompanied by a tendency towards conspiratorial beliefs. The relationship between the two was ‘dramatic’, he told me.

While researching my book – and speaking to anti-vaxxers – I came across several common themes.

The concerned parents

I spoke to Adam Gibson, a farmer and Byron Bay-based sustainable food business consultant, in February 2022.

Gibson is himself unvaccinated against COVID-19 and when one of his daughters was a toddler, he and his wife – ‘on medical advice’ – decided to delay their daughter’s vaccinations. For two years, while she was excluded from childcare, Gibson became a stay-at-home father.

Last September, feeling concerned, and ‘also a bit powerless’ at the prospect of his three primary school-aged kids being vaccinated, Adam Gibson ‘sat around a campfire’ with neighbours Jon Farriss, of INXS fame, and Charlie Arnott.

The fireside chat resulted, ultimately, in the launch of Parents With Questions (PWQ). The PWQ mission is, ostensibly, to encourage parents to make up their own minds about vaccinating their kids against COVID-19.

PWQ draws on a familiar anti-vax playbook to play on parents’ fears: vaccines are far more dangerous than we’re led to believe, and the risks of COVID-19 are exaggerated; it’s taking a sledgehammer to crack a nut. ‘All risk, no reward,’ as Gibson puts it.

Like many who mistrust vaccines, Gibson says the media has failed to tell the whole story. ‘A real choice requires two lots of information,’ he says. ‘And what we’re getting overwhelmingly in the media is one narrative only.’

What we’re getting overwhelmingly in the media is one narrative only.

The independent researchers

Many anti-vaxxers spend an inordinate amount of time poring over the latest scientific literature, reading vaccine studies or the lay explainers that follow on their heels. They see the rest of us as “sheep who just swallow what we’re fed”,” says Hornsey.

At a beachside park in Melbourne, I met up with Noela, a nurse.

In February 2021, Noela completed her immunisation provider certification, readying herself to administer the new Pfizer vaccine into the nation’s arms. But drawing on her own experience as a nurse, and information shared online, she soon changed path.

The first red flag was the blood clots linked to the AstraZeneca vaccine. In her own experience, serious reactions to vaccines were vanishingly rare. But the media was constantly reporting on this new side effect, and countries were reviewing the vaccine’s rollout.

Other red flags appeared. Vaccination schedules were changing, with wait times between first and second doses slashed. Then, as more vaccines were approved, people could choose which vaccine to get.

In Noela’s eyes, the shifting recommendations were suspicious.

A final, damning red flag was the vaccine side effects she was hearing about for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines.

Red flags are all Noela sees now. Her nursing career is all but over. Her registration has lapsed, and she has no plans to return to the job, because she would need to be vaccinated to do so.

Instead, Noela has a stash of ivermectin – which she jokingly refers to as her ‘horse tablets’ – and a recipe for making her own hydroxychloroquine.

In her bag, Noela has her ‘illegal little piece of paper’, a fake vaccine certificate she downloaded online, so she doesn’t miss out. ‘I’ve got my normal freedoms that were my freedoms before this,’ she says.

The ‘back to nature’ advocates

Some anti-vaxxers view vaccines as poisonous chemical cocktails that cause untold harms – often covered up, in their view, by an unholy alliance of power-hungry governments and profit-hungry pharmaceutical companies.

Take Maureen, who worked for years as a medical herbalist. She is healthy and feels no need to turn to Western medicine for cures that she finds in natural therapies and her body’s own defences.

For Maureen, vaccines are yet another item in a long list of chemicals that people are unwittingly exposed to. ‘We’re being bombarded,’ she said, with everything from environmental contaminants to additives and pesticides in foods, and drugs peddled by Big Pharma. ‘We don’t know what’s coming at us.’

The politically engaged

Vaccine mandates have galvanised some anti-vaxxers to become politically engaged for the first time in their lives – or to consider new, populist politics.

I met Judy who attended her first meeting of the right-leaning AustraliaOne Party in January.

She tried to weigh the group’s merits – talk of transparency and corruption – against what she recognised as clear falsehoods (laws allowing full-term abortions, for instance), and bizarre claims that she couldn’t quite place. ‘I’d like to know about the paedophilia thing,’ she mused, referring, I can only guess, to QAnon-type conspiracies about global elites running secret child-trafficking and paedophile rings.

For Judy – and anti-vaxxers like her – the party’s opposition to vaccine mandates bridged a gap I would have thought unbridgeable. Judy, who was previously actively engaged in left-leaning grassroots political processes to bolster action on climate change, was now casually curious about conspiracies associated with QAnon and the alt-right.

****

The unvaxxed are, by far, a minority in Australia, and we shouldn’t lose sight of that fact. But, in my view, we need to show consideration and respect for people whose values and experiences and access to information lead them to make decisions at odds with our own.

The rifts that have opened up over the past year can feel insurmountable. I haven’t heard from my mum in months, and I’m pretty certain that she’s blocked my mobile number.

She may have read the email I sent her recently, but it’s possible that she deleted it straightaway, or hasn’t even seen it – my brother said she’s wary of using her Gmail account because she doesn’t want Google to track her.

My brother and his kids have moved out of the house that they shared, and I imagine she has become even more reliant on the online communities she belongs to than she was before.

I bear some of the responsibility for this. I dismissed her fears, refused to engage with – or even listen to – what she was saying. If I’d listened to her concerns, I might have learned what drew her to her beliefs, and I might have been able to sow a seed of doubt in her mind about the veracity of the information she reads online.

I don’t think my mother – or Maureen, or Noela, or Judy – pose an unacceptable threat to society. But I do think that people like them could be further isolated and radicalised if they are unnecessarily excluded from society.

This pandemic will continue to surprise us. Then the next will be upon us. The way in which we communicate with each other, how we show concern for each other’s concerns, has the power to quell or exacerbate the trust we have in the media, in our experts, in our office bearers and in each other. Not just in the midst of crisis, but always.

This is an edited extract from Unvaxxed by Dyani Lewis, published by Hardie Grant Books, RRP $22.99. Available in stores nationally.

No Comments