In the days leading up to my interview with Australian human rights lawyer Jennifer Robinson, the media is consumed by one story: the sexual assault trial of Bruce Lehrmann.

It is, of course, a landmark case – an Australian #MeToo moment that has gripped the nation. Brittany Higgins’ allegations have sparked marches and fuelled outrage; they have exposed the grubby underbelly of parliament and launched a reckoning that promises to rewrite the way Canberra operates.

And yet when Robinson and I meet we don’t mention the case at all. Even though Robinson is a lawyer who is known for advocating for women’s rights. Even though we are meeting to talk about her new book How Many More Women?, which is focused on exactly this topic: allegations of gendered violence and the legal action that follows. Both of us understand that the risk of contempt of court or defamation is far too high. The safest approach is silence.

Which is precisely the point of her book.

In How Many More Women?, Robinson and her co-author and colleague Keina Yoshida argue that the #MeToo movement has encouraged a wave of women to come forward with abuse allegations – only to be met by a criminal justice system that is not only ill-equipped to handle them, but also shrouded in silence.

“The courts have become a battlefield,” they write, “where judges grapple with competing rights: her right to speak about gender-based abuse and his right to reputation.”

In this post-#MeToo world, where attitudes to sexual assault have irrevocably altered, they say another reckoning is long overdue; this time, they argue, it’s the law that must change.

Robinson and I meet on a wet Monday morning, and although it’s week two of her multi-city book publicity tour, she is impressively serene. Seated at a leather banquette on the 25th floor of a Sydney hotel, as grey clouds cling to the skyscrapers around us, Robinson is wrapped in a camel coat and red linen dress, her blonde hair swept into a classic French twist. In an hour she’ll be on her way to her next media interview, and then to the airport for another event, but right now, she is poised and focused.

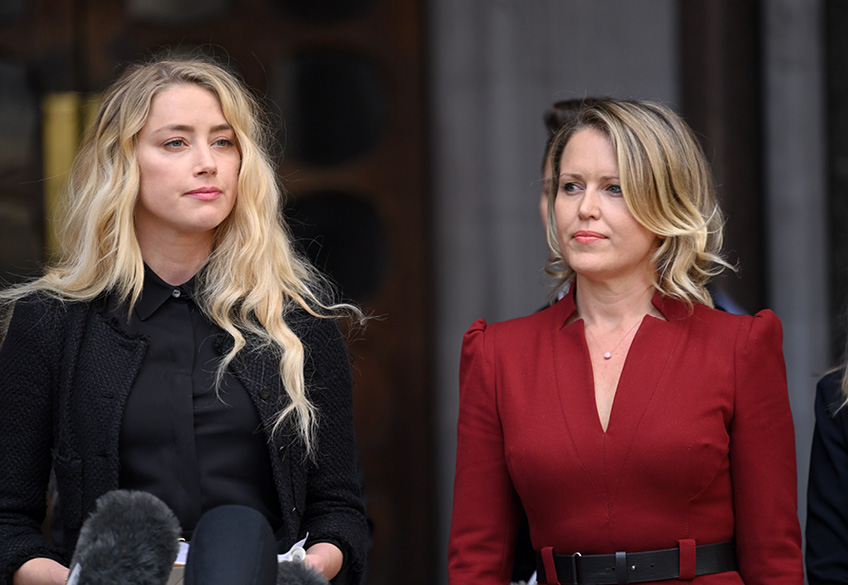

But that’s what you’d expect of Robinson. This is a woman who has campaigned for West Papuan freedom fighters, who has acted for Wikileaks founder Julian Assange for over a decade and who recently faced the white-hot glare of the world’s media while representing Amber Heard in Johnny Depp’s defamation case against The Sun newspaper.

She and Yoshida were compelled to write How Many More Women? after being struck by the myriad ways in which the legal system was inadvertently conspiring to silence women via laws on privacy, contract, defamation or contempt of court.

“I was frustrated. My co-author and I were both frustrated,” says Robinson, who adds that both she and Yoshida had grown particularly concerned by the rising numbers of “rich and powerful” abusers who were weaponising defamation laws and non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) as a way to shut down allegations of abuse.

Many of these men are well-known. Hollywood movie producer Harvey Weinstein was able to abuse women for more than three decades thanks to the NDAs he forced them to sign. Bill Cosby deployed this tactic, too, and Jeffrey Epstein’s abuse continued, unchecked and unreported for years – despite swirling rumours and victims who were willing to go on the record –because media outlets were too fearful of being sued for defamation.

And yet those cases are just “the tip of the iceberg”, says Robinson. Behind these high-profile trials, she explains, lurk countless other cases that are just as dark, but can’t be reported on.

“There’s so much you don’t see because things are settled confidentially. I cannot tell you how often my colleagues and I are asked to advise rape crisis centres, survivors, journalists, friends, family members who are concerned about their loved one who are facing legal threats,” she continues. “People who are coming to us for advice like ‘How can we campaign about the murder of our daughter without being sued?’”

There’s so much you don’t see because things are settled confidentially.

Robinson describes the way that the legal system acts to silence and control women as “gendered censorship”, and she is determined to put a stop it.

“We want people to understand the problem. That’s the first goal. We want more women than we could ever advise in our chambers to understand the risks they face.”

It’s for this reason that Robinson writes, in depth, about the case of Amber Heard in the book. Robinson became co-counsel for the actor in 2018, shortly after Depp sued The Sun for defamation for describing him as a ‘wife beater’.

Leaning back in her seat, Robinson recalls the first time Heard got in touch. “She reached out to me through friends,” she remembers. “My impression was that she was smart – incredibly smart – and very warm. A woman’s woman.”

Heard herself was never on trial, Robinson adds. The actor hadn’t contributed to The Sun’s article or been interviewed for it. But she chose to give evidence in support of the newspaper, and subsequently found herself in the eye of a global media storm.

“I had worked on cases that had drawn a crowd before, but I had never seen anything like this,” writes Robinson, recalling how paparazzi and Depp fans would press up against the window of the car, screaming obscenities, as she and Amber drove into court. “In Johnny Depp, it was as if they saw the victim of a cancel culture supposedly obsessed with bringing white masculinity down.”

What few people realised about Depp’s legal action was that it was carefully choreographed. As Robinson points out in her book, The Sun wasn’t the first media outlet to paint Depp as an abuser (The Guardian had previously referred to him as a “wife batterer”) but Depp chose to sue the far less sympathetic tabloid newspaper. Depp also elected to litigate in London, a city that, as Robinson notes, is so notoriously pro-claimant it is known as the “libel capital of the world’.

In the end, The Sun prevailed, and Depp lost. But a second case was held in the US, and this time it was live-streamed, making the London trial look sedate by comparison. Vitriolic videos flooded social media and anti-Amber merchandise was sold online. “The worst I have seen was a dildo created by a sex toy company in the shape of a bottle so women could “pleasure” themselves to new “Depp-ths,” writes Robinson.

Just as How Many More Women went to print, the US verdict came in: this time, Heard had lost.

“We were writing the book long before the Depp case,” says Robinson with a sigh. “But… it is obviously a terrifying case study about what happens when women are sued for defamation.”

For Robinson, the issue of violence against women is not merely professional, it’s personal, too.

Growing up in Berry, NSW, with a horse trainer father and a teacher mother, Robinson enjoyed few of the luxuries or legal connections you might expect from a lawyer who has been described as one of Australia’s “star exports”.

She attended her local school, Bombaderry High, and worked three jobs to put herself through university before winning a Rhodes Scholarship that took her to Oxford University in the UK.

“Nobody expected me to be where I am,” she says flatly. “I had to work so hard.”

But while Robinson’s background was relatively humble, it was always safe – a fact that was reinforced by the time she spent with her grandmother, who worked in domestic violence refuges. “I was very alert from a very young age about the impact of domestic violence on children and our families because of what I saw with her. My sister and I would go on outings with the kids living in the refuge, so we were very aware of what a privilege it was that we didn’t have that [violence] at home.”

Later, at law school, Robinson experienced sexual harassment at two of the three law firms she worked in. “I think every woman who’s worked in the law will have [experienced] similarly inappropriate behaviour,” she says of the sexualised comments and inappropriate advances that occurred at work parties.

At the time, she reported the behaviour to HR, but didn’t consider litigation.

Does she wish she had? “In a way I wish I did,” she says slowly. “I wonder how that would have gone. The thing is that I was just a student… I wasn’t in the position of power that I am now. And we need to recognise that it is difficult for women in that position to speak out, and we need to make it easier for them to do so.”

Later, we circle back to the idea that many women who have experienced violence or harassment don’t litigate – and often don’t want to.

“They just want [the violence] to stop,” says Robinson. “Sending someone to prison is not the justice they want. They want to protect themselves and protect their family. They want to protect other women.”

Robinson is referring to the women she has interviewed or defended, but her reflections could just as easily apply to a young law student who has been harassed in the earliest stages of what will go on to become a dazzling career – and chose not to risk it by litigating.

So, is this the answer: a wholesale reimagining of the way that sexual assault cases are managed – away from the courts?

“We need to talk about abuse in our society outside the context of the criminal justice system,” she says carefully. “It’s tricky. The standard of proof [for sexual assault convictions] is purposefully high because you don’t want to unjustly detain anyone. But we [also] need to recognise that when someone is acquitted it doesn’t mean that she lied. It means [prosecutors] couldn’t reach the high standard of proof.”

At the very least, she says, we need to be able to speak more openly. “We need a discussion about costs in this country and the damages that are awarded. Because they are just beyond the capacity of most journalists and media organisations and certainly most women,” she says, adding “What does free speech mean if you can’t afford to defend it?”

And with that, Robinson is off, on her way to the next event on her publicity tour.

A few days after we meet, there is a shocking development in the Bruce Lehrmann trial when the jury is discharged due to misconduct. The following day, Brittany Higgins’ pale, serious face stares out from the front page of The Daily Telegraph. Higgins has been photographed shortly after making a statement on the steps of the court, and her hand is covering her mouth. The headline is splashed across the page, and as if to underline every point Robinson has made, it reads: DON’T SPEAK.

Want more stories like this? Sign up to PRIMER’s free weekly newsletter.

No Comments