It’s not a house you’d notice. Weatherboard, with a neat fence low enough to hurdle, and pretty apricot curtains in the windows. There’s a Toyota Corolla parked outside.

There’s nothing, really, that sets this scene apart from any other ordinary Aussie home; but for Jenny, 73, ‘ordinary’ is a victory. She only recently escaped a situation, in which she lived, not in a house, but in her Corolla.

In her sixties, after the breakdown of her marriage, Jenny shared a house with a neighbour. He drank too much and smoked pot, but she didn’t have the resources to live alone. The situation soon became abusive. ‘He’d be drinking and smoking at seven or eight o’clock in the morning,’ says Jenny, who is tiny, and when I meet her, neatly turned out in black trousers and a blouse and discreet gold jewellery.

“He took my skin off my arm from here to here. Not because he belted me, but he’d shove me into the fridge, or slam a door on me.”

That’s how she ended up in the Corolla, alone but for her dogs. Parking outside McDonalds, in church yards, and in suburban streets for nine back-breaking months.

It was a nightmarish period; filled with terrifying nights when drunk men tried to lift her car, and smash its windows: acute pain and illness, thoughts of suicide. But let’s fast forward to when her fortunes changed: deliverance, in the form of a car park.

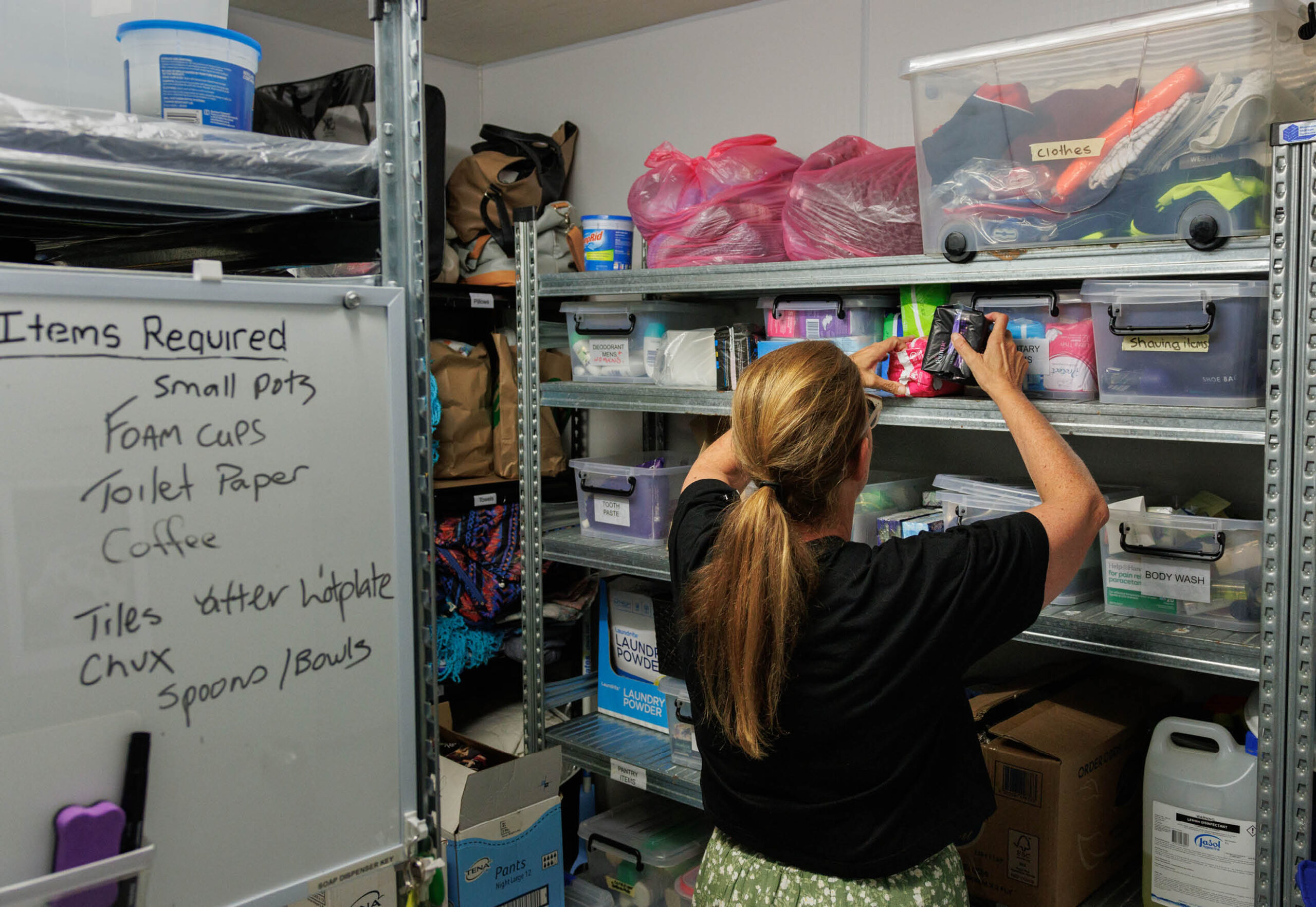

Hidden behind a hill, in Lake Macquarie, there’s a gravel yard, set aside for the homeless, who are living in their cars. By prior arrangement, you can sleep there, in your car. But there’s also a small kitchen. A sofa to sit on. Some basic supplies.

And a bathroom. A gloriously clean shower, and toilet.

Jenny calls them beautiful. Because if you’re homeless, and sleeping in a car, keeping clean and having access to a toilet are not daily privileges you take for granted. It was at this car park, which acts as both a shelter and a place to connect with services like healthcare and housing, that Jenny began to get back on her feet.

Most people think that today, in Australia, if women leave a violent situation, they can escape to a refuge or charity. The reality is much more dire.

It’s estimated that at least 122,000 people are homeless every night. For women, the leading cause is domestic and family violence – and the painful truth is that when women leave violent homes, often, there isn’t enough accommodation to support them.

“We don’t want to discourage people from seeking help. There are vacancies that come up, but most services are operating over capacity, well and truly,” says Annabelle Daniel, CEO of Women’s Community Shelters.

As a result, too often, women are diverted into motels, caravan parks and repurposed aged care facilities around the country. In Victoria now, 80 percent of women who seek to leave domestic and family violence are placed in motels.

The housing crisis has only exacerbated demand. To cope with the wave of women and children overflowing from social services and into homelessness, charities and churches are establishing a growing number of pop-ups and car parks.

In Queensland, the charity BedDown partners with car park operators to provide pop-up shelters for the homeless. It’s currently raising funds to transform an Ipswich restaurant into a shelter that sleeps 12 women every night.

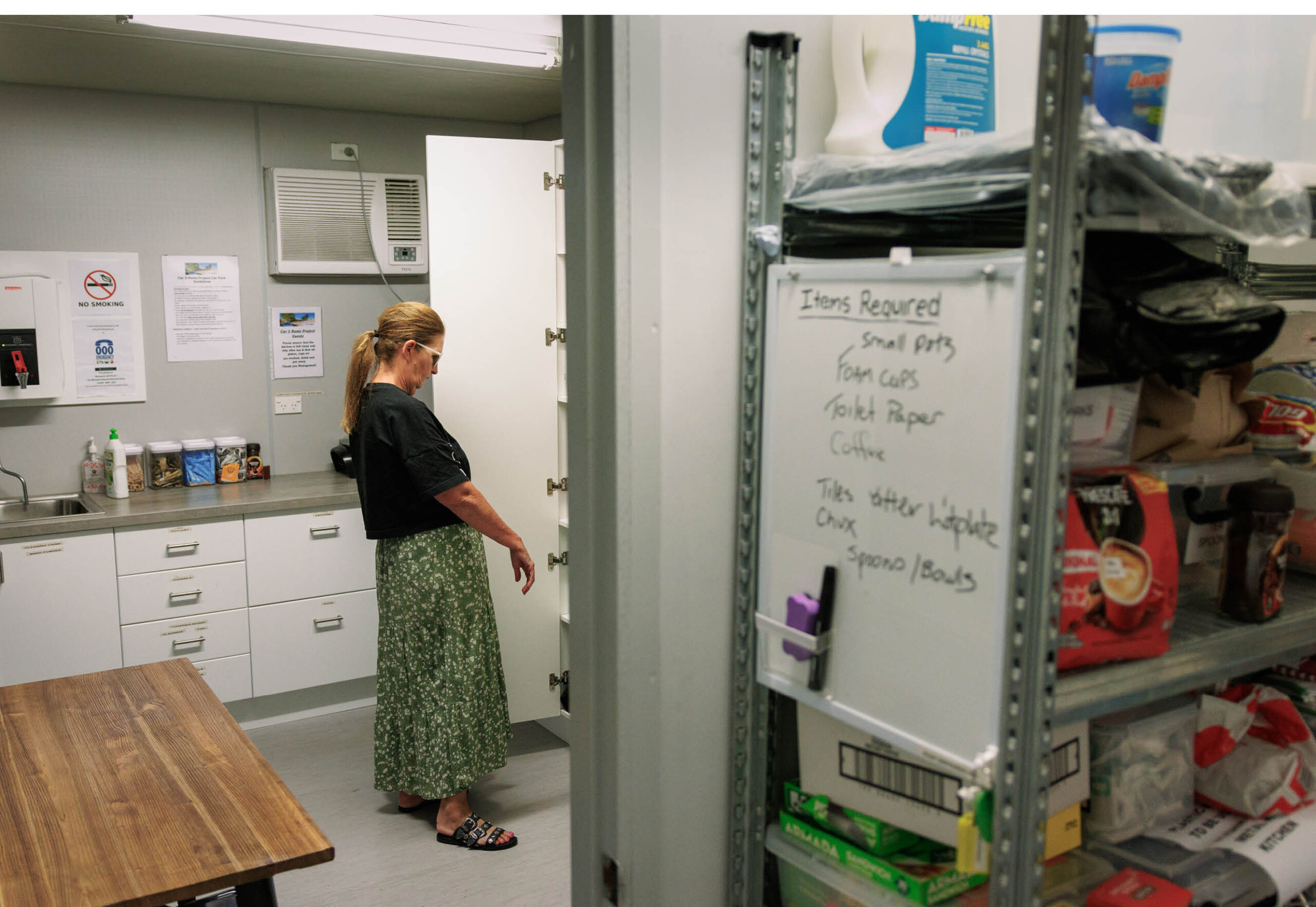

Danielle Whyte runs the car park and connected services at Car2Home in Lake Macquarie that gave Jenny safe haven. She says that when clients first see the facilities, it’s the bathrooms they’re most affected by: some women cry on seeing them. There’s dignity in a clean bathroom.

Car2Home was once called Our Backyard. It’s operated for 10 years and started out as purely a shelter for people to sleep in their cars with a sense of safety and security.

“It started out as a ‘band-aid’. There were plenty of volunteers, but no pathways to housing, or casework. Now we’re moving into doing our own social housing.”

Danielle lives in the area herself, with her family, and has a background in law and financial counselling. She’s calm and determined, but not detached. As she shares with me in her modest office the stories of some of the clients who’ve slept in the car park, she remembers each in striking detail. The car. The way they’d arranged it. Why they were there. How long they stayed.

Car2Home is funded by a local church – Danielle is one of two paid employees. Christmas is their busiest period – when other services shut down, there’s more alcohol abuse, and tensions in relationships intensify. She says around half the rough sleepers who come through the car park are women.

“We had a lady come up from Tasmania – in a Hyundai Getz. It had all her belongings in it. After I met her and saw her situation, I just said you’re not going to survive this weekend in that. Rain was forecast so we paid for a hotel. She just really needed to be lying flat, in a bed.”

She tells me that of the women who use the service, “99 per cent” have been exposed to violence. Even the young girls. And usually that manifests itself in a few ways – but most often substance abuse.

“They get so stressed, figuring out logistics, where to go, worrying about their cars, how to sleep. If they don’t have a mental illness beforehand, they soon will, once they start sleeping in their cars.”

Danielle Whyte is realistic about the service they offer.

“In Lake Macquarie, homelessness increased by 35 per cent in the last census. We want to see social housing in NSW get sorted out. But until that happens, if we can help one person at a time, get into one house at a time, that’s progress. If you sit there and say the problem’s too big, nothing is going to happen.”

Jenny is that one person, with that one house. She and Danielle started out as caseworker and client, but these days they’re friends. Danielle drops round when she’s in the area. Jenny doesn’t have many visitors, and doesn’t like to leave the house, but she likes company, when she’s feeling well.

We want to see social housing in NSW get sorted out. But until that happens, if we can help one person at a time, get into one house at a time, that’s progress.

The day I talk to Stephen Simpson, the CEO of Homelessness Queensland, he’s surrounded by moving boxes: his landlord is putting his house on the market, so he’s in the process of packing up his home office. The boxes are a backdrop to our video call. He’s seeing housing insecurity up close…

He explains that although there’s been a significant investment in refuges and temporary accommodation in his state, demand has been compounded by the cost-of-living crisis.

“In a relatively short space of time, we’ve gone from a situation of affordability to one where what was affordable is now out of reach. What used to be $400 a week, is now $550 or $600. That’s so expensive, if you’re on a disability support pension, or youth allowance or any sort of benefits, let alone working on a low-income salary. It’s really difficult.”

For women escaping violence, the labyrinthine social housing system can feel impenetrable. “A lot of people leave home in a hurry, they don’t have the right documents. The system is really complex, and one part, like the family court, doesn’t talk to another.

A lot of people leave home in a hurry, they don’t have the right documents.

“So, they have to navigate a really complex system, and try to fit into a box. Housing is never permanent. It’s always temporary. It’s crisis driven. Say you get into a shelter, then you might get some transitional housing. Then into another form of temporary housing, for a period of time, trying to secure either private rent or social or affordable housing. So, you get people bouncing backwards and forwards.”

For many women escaping violence, living in a car is simpler in some ways than trying to find temporary accommodation. “It feels safe, because they don’t have to disclose the embarrassing thing that happened to them: the black marks, bruising, the scratches and so on. And so they hide. And that’s really sad. We need to think about our response to that.”

Author and journalist Trent Dalton understands the interplay of homelessness and violence better than most. His most recent novel, Lola in the Mirror, tells the story of a daughter and her mother living in their car under a bridge in Brisbane. It draws on his family’s own experience of domestic violence and the threat of homelessness – but also on a decade spent reporting on the issue.

“One of the things I’m trying to write about is this idea of what does it take to be human, and what does it take to have a home. And I’m interested in the ways identities are lost. It’s such a massive thing for people on the street. Not just your physical identity, your driver’s licence or your birth certificate. Everything gets stripped from you – and how you feel about yourself. Everything I’ve tried to write about is this idea that you lose your sense of self. Who you are. And dignity is so tied up in that. You’re just so raw.”

Speaking from his home in Brisbane, he says people reading the book have reacted with surprise, telling him they hadn’t realised there was a homelessness problem in their own streets, that women and children are living in cars.

“And I think, so much depends on how much you are willing to open your eyes and see it. If you went down in Brisbane to most suburbs, you’d find one or two cars parked up; particularly near CCTV cameras, or places near an all-night convenience store, where there’s a bit of lighting, a bit of safety. They’re there. They gather in these mini-shopping centres. And the government is not moving them on, because they don’t have better options for them.”

If you went down in Brisbane to most suburbs, you’d find one or two cars parked up; particularly near CCTV cameras, or places near an all-night convenience store, where there’s a bit of lighting, a bit of safety.

Stephen Simpson worries that the rise of pop-up shelters and secure car parks is a band-aid solution, and that the focus should be on permanent housing.

“I’m not downplaying the impact for the people who use it. But it feels a considerable shift away from looking for permanent safe housing for people.”

Annabelle Daniel agrees. “Some interventions, while well-meaning, can actually put women at more risk. In order to protect people, especially women experiencing DV, you need to have a solid specialist response to that. But I’m heartened by communities seeing the problem, and responding to it.

Beddown’s Norm McGillivray wants a national body set up, to advocate and work together to get people off the streets, and out of cars, and into temporary and transitional venues.

He argues that homes are not coming anytime soon to meet demand, so we need to look at other ways to help. He wants government, industry and not for profits to work together, to activate what he calls empty and underutilised assets, until enough housing stock is online and available.

Back at Car2Home, Danielle is finishing up for the day, after filing housing applications, which she says takes forever, and trying to fast-track a medical procedure so a homeless client can return to work.

In her analysis, the sector is dogged by people looking for quick fixes when quick fixes don’t work. “There’s no forward planning or collaboration between local, state and federal governments. In NSW last year, the government spent 57 million dollars on temporary accommodation and motels. That bill is through the roof. Someone needs to say okay, this is the budget, what infrastructure do we need. Even just renovating the public housing properties that are sitting empty would be a start. They can only do bandaids.”

Jenny remembers the first time she saw the two-bedroom house, that is now her home.

“I loved it straight away. I remember thinking, a gas stove, fabulous! And a yard for the dogs. They went bananas. Their personalities changed within days – they were fed up with being in the car. I used to say to them at night, I’m fed up too.”

Car2Home worked with a community housing provider to secure the house for Jenny. She pays half the market rate for rent. She might have had a home sooner, if she’d been prepared to give up her dogs, Elly and Ruby. Most refuges won’t take people with pets. But she says “they’d never been with anyone else but me all their lives. And really, if I’m truly honest, emotionally I depend on them.”

Her time in the car feels firmly in the past, but her walking stick is a reminder of that time of hardship. Her physical health is poor. And while Jenny says she’s fairly mentally strong, she does struggle at times with her memories.

When I thank her for talking to us, for taking the time, for letting us into her lovely home, she says she wants to tell her story in case it helps someone else, like her. Just one person. That would mean a lot.

Want more stories like this? Sign up to PRIMER’s free weekly newsletter.

1 Comment