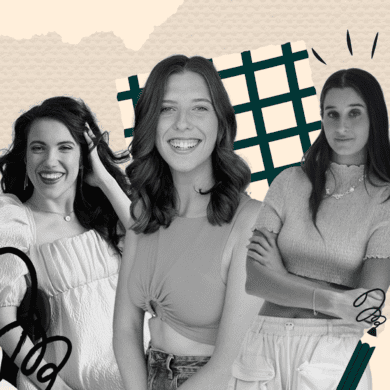

After a busy day at work, social justice lawyer Famin Ahmed sits down in front of the TV and starts to sew. This isn’t just a hobby, though – Ahmed sells her cheery sunhats, scrunchies and printed t-shirts through her Instagram account, Famin Makes. All of the profits go to Women’s Legal Service Queensland, which offers legal support to women experiencing family violence.

So far, Ahmed has raised over $65,000, and received the University of Queensland’s Distinguished Young Alumni Award for her commitment to social justice.

“The project is also a conversation starter,” she says. “It gives people the tools to bring up the topic of domestic violence in a way that feels natural, which often captures a broader audience. In that sense, the impact doesn’t just stop at the purchase – it keeps going, like a butterfly effect.”

Ahmed has raised over $65,000, and received the University of Queensland’s Distinguished Young Alumni Award for her commitment to social justice

What was the moment that changed everything?

“In my last semester of university, I went to one of the drop-in sessions at the Women’s Legal Service with a friend, as I have personal experience of domestic violence. By the time we arrived, it was already full and we were turned away. A woman behind us wearing corporate clothes, who I assumed was one of the lawyers, was also turned away. She just burst into tears. I thought about how long it had probably taken her to get to the point where she had enough courage to even come, and what she must be going home to.

“That was the moment I realised that, despite being a victim survivor myself, I still had a very specific perception of what DV looked like. Of course, there are circumstances that make people more vulnerable to it, but DV’s base lies in power and patriarchy, so it really doesn’t discriminate. That was also the moment I realised how critically underfunded Women’s Legal Service is. I still think about that woman today.”

More clothing companies and brands now have a charitable aspect. Why do you think people are increasingly drawn to this concept of ‘wearing your values’?

“In this case, I think domestic violence feels like such a big issue. People often feel like they don’t have the power to change it – that it’s too hard, too complex. Purpose-led fashion lets people feel like they can play a tangible part in the change. I polled my Instagram followers last year and 80 per cent of people who’d bought a hat said it had allowed them to start a conversation about DV. That’s really cool.”

Tell us about a moment that makes everything worthwhile.

“I’ve been doing a bit of speaking recently about Famin Makes and so for me, it’s when I can actually see people’s perceptions change. I recently spoke at a local rotary club where the audience was a lot of middle-aged white men, and they were absolutely gobsmacked when I shared my story. They had no idea the issue was so prevalent or so local. It’s really rewarding seeing people change their attitudes as a result of my work because at the end of the day, [DV] is a cultural issue. Yes, we need funding and support services, but in order for real change we need to address the cultural attitudes on the ground.”

When you’re not making hats, what do you love doing?

“Walking! I love walking. I walk home along the river every day and on the weekend I’ll try to get out in nature. I usually watch TV while I sew, so walking is the one time where I’m really mindful.”

What’s the best advice you’ve been given?

“Know what you want to do, but be open to where the path will take you.” I could never have predicted that Famin Makes would take off like it has, nor could I have predicted the opportunities that have come from it. You truly never know what doors will open, so although I know it’s a cliche, I do believe in taking things as they come and making the most of them.”

Finish this sentence: nothing feels better than…

“Nothing feels better than knowing something I have said or done has convinced someone to care about a cause bigger than themselves. Growing up it was always expected in our family that we would consider people less fortunate than us, especially coming from Bangladesh. I really believe everyone has a responsibility to help people who are not as lucky as them and I hope that my work in some way facilitates that.”

Want more stories like this? Sign up to PRIMER’s free weekly newsletter

No Comments