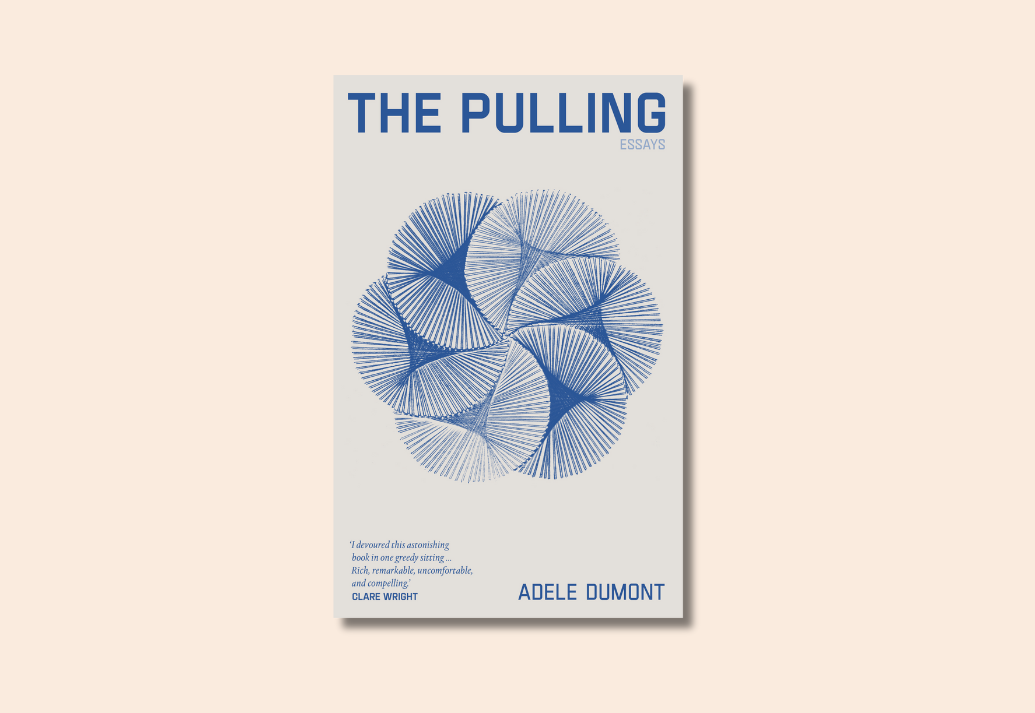

I had never been one to pay too much attention to my hair, nor indeed to any part of my body, save for picking at my nails. But in my HSC year, aged 17, as well as learning about the Ancient Greeks and the Victorians and the Post-Impressionists, I began to discover the anatomy of my hair.

A lot of the ends were split, and tendrilous; I would peel the splits up, far as they would go before detaching from the main hair’s shaft. And then I started to do this other thing, an arresting thing …

Each individual hair I pulled out — curled and coarse — I’d stretch out tight, and take in the enormous length of each one unfurled. If I ran one along my thigh, it would reach from my hip to my knee. And how dark. I wasn’t used to thinking of my hair as being that dark. All the bits on the outside were lightened by the sun, but the hidden bits, the bits that grew out from the central part of my scalp — they never got to see the sun, so they were almost black.

The whole process was mysteriously painless: the hairs on my head, I learned quickly, sit as shallowly as birthday candles in a cake, can be removed as effortlessly as a grape can from its stem.

Before I go on, let me say that unless you are of my kind, doing what I do would hurt you. And I would believe your hurt, because occasionally when a hair of mine catches in the Velcro of my bike helmet, or when some of those tiny vellus hairs on my arm get stuck in the glue of a bandaid as I’m trying to coax it off, I can’t help but release a tiny yelp.

The whole process was mysteriously painless: the hairs on my head, I learned quickly, sit as shallowly as birthday candles in a cake

Back in that HSC year I had so much hair, and it was all so thick that I (deludedly, I now realise) never contemplated the fact that by pulling out individual strands I was doing any damage. In fact, if anything, I thought I was tidying up my head of hair by thinning it out a little. Like a gardener might thin out seedlings, so that there aren’t too many roots all vying for the same patch of earth.

Pulling out just one shaft of hair at a time always felt so insignificant, something imperceptible. Who could notice one strand missing from a whole, overly thick head of hair?

Once they’d been removed from my head I would stuff the hairs away down the side of my bed. These discarded hairs held no interest for me. One day, I was cleaning my room — always a rare occasion as a teenager — and I shoved my hand down the side of my bed, collected all the hairs I could and rubbed them together between my palms into something resembling a scratchy ball of wool. I kept on scraping up more hairs and adding them to the ball. I shoved the whole thing into a plastic bag, this object the size of a small bird’s nest and when I went to double-bag it, so I could dispose of it in the garbage bin at the end of the driveway, what threw me was the weight of it. I never knew hair had weight. I can still feel the heft of it.

Maybe the word evidence is a strange one to use here. I wouldn’t use it for the tiny, blunt hairs that stuck to the sides of the bathtub after I’d (secretly) shaved my legs, or for the small mounds that I’d seen carpet the floor of hairdressers in shopping arcades. But there was no doubt in my mind that that was what was contained in the plastic bag. Evidence.

By this point in my life I’d already internalised the belief that the way I was always picking at my nails was ugly and unladylike (unhumanlike even), and this new habit seemed far more aberrant. Even picking parsley from the garden for dinner, my mother had taught me the ‘right’ way to pinch just the tips, not to pick too much from the one part of the plant, and certainly not to yank at it in such a way the roots might be dislodged.

And so now, with my hair, there was no doubt whatsoever in my mind that what I had done was unspeakable, and wrong.

I don’t know when exactly I realised I wasn’t able to stop. I do remember the shock and strange satisfaction of discovering, right at the crown of my head, a small circle of skin that I’d pulled completely clean of hair. This circle grew and grew over the ensuing months, and with it, my determination that nobody would discover the damage.

At first, concealing the site was straightforward; I pulled what remained of my hair over it. Over time, my arrangements had to become more meticulous, but eventually I could no longer hide what I’d done. If anyone near me expressed concern, I made it clear this topic was off-limits. Privately, I experimented with wearing thimbles, gloves and BandAids over my fingers in an attempt to curb my compulsions. And when these strategies failed, I took to wearing wide headbands and hats, and even a hairpiece.

I don’t know when exactly I realised I wasn’t able to stop

My shame by now feels self-evident. But if I had to articulate it, I’d say its real locus is that all this is – ostensibly – my own doing. I am the one who tears the hair from my head and then savours each slick root. I remove it from where it belongs and feed it to wear it does not, so that the roots that belong in my scalp end up on my lips, in my mouth, in my stomach. I mean, who does that? If my hair had fallen out ‘naturally’, or if it had been a side-effect from some sort ocf medical treatment, I don’t believe I would feel half the amount of shame I do.

I’m ashamed of how my compulsions have got so out of hand and have expanded to be such a large part of ‘me’. I’m ashamed that I’m unable to stop. And, maybe most painfully of all, I’m ashamed of my own shame. We’re encouraged, now, to feel pride towards those aspects of our identities that might in times past have been deemed shameful (our fatness, our sexuality, our kinks) but I am so stuck with my shame. It feels socially unacceptable; taboo; as though it belongs to an earlier, medieval time.

There is no clear consensus about why anyone might begin to pull. Trichotillomania – the technical name for my condition – is ultimately elusive in its causes and in its classification, and so, too, in its treatment.

In my own case, I suspect some undercurrent of anxiety that manifested in biting my nails as a young girl, and later tearing out my hair. This made me ashamed, distancing me from other people and exacerbating the negative feelings I had about myself – feelings I attempted to relieve through the soothing rituals of pulling. Afterwards this heightened my anxiety… ad infinitum. To date, no single method of treatment has produced long-term, consistent and reproducible results.

When I first discovered that my illness had a name, I was immensely hopeful that it was just a matter of time before someone would discover a treatment. Over time, that hope morphed into frustration and despair. But now, over a decade on, hope or patience or anger – all this feeling strikes me as futile. Even if a magic bullet were found tomorrow, I find it impossible to believe it would do much to remedy a case as severe and entrenched as my own. Instead, I need to make do with the tools I have at my disposal, limited and unreliable as they may be.

For a long time, I was intent on keeping my secret intact within me

So why did I decide to write about my compulsion to pull, to reveal my secret shame to strangers?

For a long time, I was intent on keeping my secret intact within me, adamant that any attempt to write about it would destroy its wholeness. I can’t really account for the shift; all I know is that another need in me grew: for my secret to take up some kind of space in the world outside my own body. Outside my mind, my scalp, my fingertips.

For me, writing is an admission that my illness cannot be made to disappear into thin air. The best I can hope for is for it to be displaced. Writing is an attempt to displace (or purge?) my secrets out of my body and onto paper. So that they still have a home.

No Comments