There I am. In that old black-and-white passport-sized photo, perched on my mother’s knee, wide-eyed and waiting. Back in 1977, babies didn’t have their own passports. But I’ve seen my Guyanese birth certificate. All the details have been written sideways by a left-handed registrar.

Wedged between Venezuela and Suriname, Guyana is a nation in South America, but also part of the Caribbean. It’s where my father was born way back in 1937. And what do I have left of it now? It’s my birthplace but not my homeland.

That picture with me on my mother’s knee provides safe passage to Sydney in 1978. Mum has run away from it all – Catholicism, sexism, parochialism – only to land right back where she was born and bred.

Gone is the blackness of my father, who I will not see for another twenty years. These are my people now.

Mum has run away from it all only to land right back where she was born and bred

This is the time I like myself the most, before I know what colour means. When the lightbulb of consciousness switches on at around four years old, I don’t see my skin. I see the family I have been raised with and I assume that I am white, just like them. Safe in my mother’s land.

In 1979, Mum gets an academic job interstate and we move into university housing in Canberra. Scholars from all over the world – Papua New Guinea, Poland, Denmark, India, Kenya, Peru, Canada, Pakistan – live in Carroll Street with their families. You are the odd one out if you ‘come’ from Australia. We live in our own little United Nations bubble, separate from the white middle-classness of 1980s Canberra.

Outside of Carroll Street I often catch a stranger’s furtive, accusatory glance. Not Aboriginal. Then what – adopted? It feels like we have been charged with conspiracy to commit fraud and are perpetually awaiting trial. Whenever I pass an Aboriginal face in the street, as uncommon as that is, I hope for some kind of reassuring transaction: ‘You’re okay. I see your shame. I feel it too.’ Do they hear my silent offering? Can I seek kinship here? I often think so, whether this is real or imagined.

It is certainly rare to see African faces in Canberra as I grow up. With no reference points for my dad’s existence, he becomes even more of an alien concept.

My mum befriended a family from Guyana once. The girl, Nadia, was my age, and we were so proud we’d found each other. We sat in her room one day with a cassette deck recording our simplistic anthem of solidarity: ‘We’ve got brown eyes, brown eyes. And we’ve got brown skin, brown skin. And we both come from … the Caribbean.’ Then we ran down to the playground near her house. A group of boys called us ‘niggers’. Our simple joy and sense of belonging in the world was gone. Shame sat heavy in our stomachs as we walked home. Not a word spoken between us.

When I am about 10, Mum comes to school one day. She calls out my name, but I pretend not to hear. Her presence embarrasses me; kids ask how I can be brown if she isn’t. It’s then that I really see my skin. My father has made me visible in the worst possible way. I hate him and I hate myself.

I especially hate my dark lip hair. ‘You’ve got a moustache!’ others say. I am miserable, and in class my hand hovers around the offending area. Mum gets hair removal cream; it’s stinky and messy, but I do not want the legacy my father has given me.

And the craving for whiteness begins.

Kids ask how I can be brown when my mum isn’t

The first and most desirable form I crave is mother whiteness. I covet my mum’s long blonde hair. I resist my own tangle of fuzzy curls, tie it up into a bun, away and out of sight. Mum wants to see it, tells me that it’s beautiful. It’s okay for her – the brush goes straight through her shiny golden mane.

The second form is waiting-room whiteness. This is a cloak of invisibility that shields you from penetration when you walk into a specialist’s office. When I enter without the cloak, everyone looks up from their trashy mag and stares.

Third is the pretty whiteness that permeates every single television show and cover of Woman’s Day: ‘our’ Nicole, Cate, Rebecca, Tracey. How brave, talented and beautiful they are. The screen and page reiterate who’s really important. I want to turn inside out, show everyone that whiteness lives inside me, too.

I resist my own tangle of fuzzy curls, tie it up into a bun, away and out of sight

It’s at school where the fear and ignorance of adulthood resonate the loudest. A boy rides past and calls me a sambo. Mum, my fierce protector, chases him down, gives him a talking-to. I can’t hear what Mum says, but the boy looks over and stares straight through me. I am nothing to him, but have caused trouble all the same.

On a trip to Katoomba, two teenage boys make monkey sounds at me. I try to focus on the Three Sisters behind them. We’ve come here to look at the wondrous rock formations. The boys tell me to go back to Africa. I do not have the words and the confidence to explain: ‘I’m not from Africa. And Guyana is not the same country as Ghana. Although my father did work there, as a physics teacher. This is where my middle name, Akosua, comes from. It means “Sunday’s child”. I was actually born on a Thursday, but Mum did not like the name Yaa. Being African means lots of things and speaks to many places and people outside the continent. So go fuck yourselves.’

I have both the words and the confidence now. But I cannot go back and help that little brown girl.

The boys tell me to go back to Africa. I do not have the words and confidence to say I’m not from Africa

I grow into a teenager. Both self-conscious and self-assured in my hormone-fuelled becoming. On the way to what, I am not yet sure. In Year 7, I tamed my curls with a handful of gel.

But in Year 10 the hair comes out. My hair has always been a conspicuous marker of difference. Letting my hair out is a quiet rebellion. I am testing myself, as well as the world at large.

When I turn 18, there’s sex, drugs and rock’n’roll aplenty at the Australian National University. Now my Afro-Caribbean heritage and womanly curves make me desirable. ‘Don’t you see it though? I’m whiter than sliced bread underneath!’ I want to tell people. It leaves me feeling empowered to provide some kind of rite of passage for those middle-class white boys who have never left the nest of old money, security and tradition. Exoticism affords me an authority I’ve never had before. I don’t deny it, nor am I ashamed. I am not a victim. We are all playing games as we move from becoming to finally and undoubtedly being.

That provocateur is twenty years older now.

I don’t know if Australia is any less racist than it was when I was growing up. I did, however, feel certain that when I had a child they would share my colouring, and would never have to explain themselves as I had often done. As it turns out, my boy has straight blond hair and pale skin. In the playground at his school I’m asked the same question again: ‘Why are you two different colours?’ But this time, I crouch down and explain that my boy’s skin comes from Germany, Ireland and Guyana. I wax lyrical about the wonders of genetics until the curious kid just wants to go play again.

The question ‘where do you come from?’ is for many people inherently divisive because the subtext speaks so loudly – you cannot be from here, and are therefore Other. But the opposite of otherness is to be known. I went looking for Australian women connected to the African diaspora. I wanted to see them, to be known by them and for them to know me. We talk; we create new conversations.

I can still hear ‘The Brown-eyed Girls’ in my head. That tediously repetitive song I wrote with Nadia, the only other Guyanese kid I ever met, who understood how you could be proud and lost in equal measure. I sometimes wonder if she remembers walking home from the playground that day, or if it’s all part of a past she’d rather forget.

But there are other songs now, too. My son’s school always plays music through the loudspeakers just before the morning bell. One day, I hear a tinny steel drum, dancing on the back of the wind, calling us forward towards the school gates. ‘Listen,’ I say to my boy. ‘This is Grandpa’s music from the Caribbean. It’s called calypso.’ I want a loudspeaker myself. ‘Stop, everyone! Stop and listen to the joy it brings,’ I’d say.

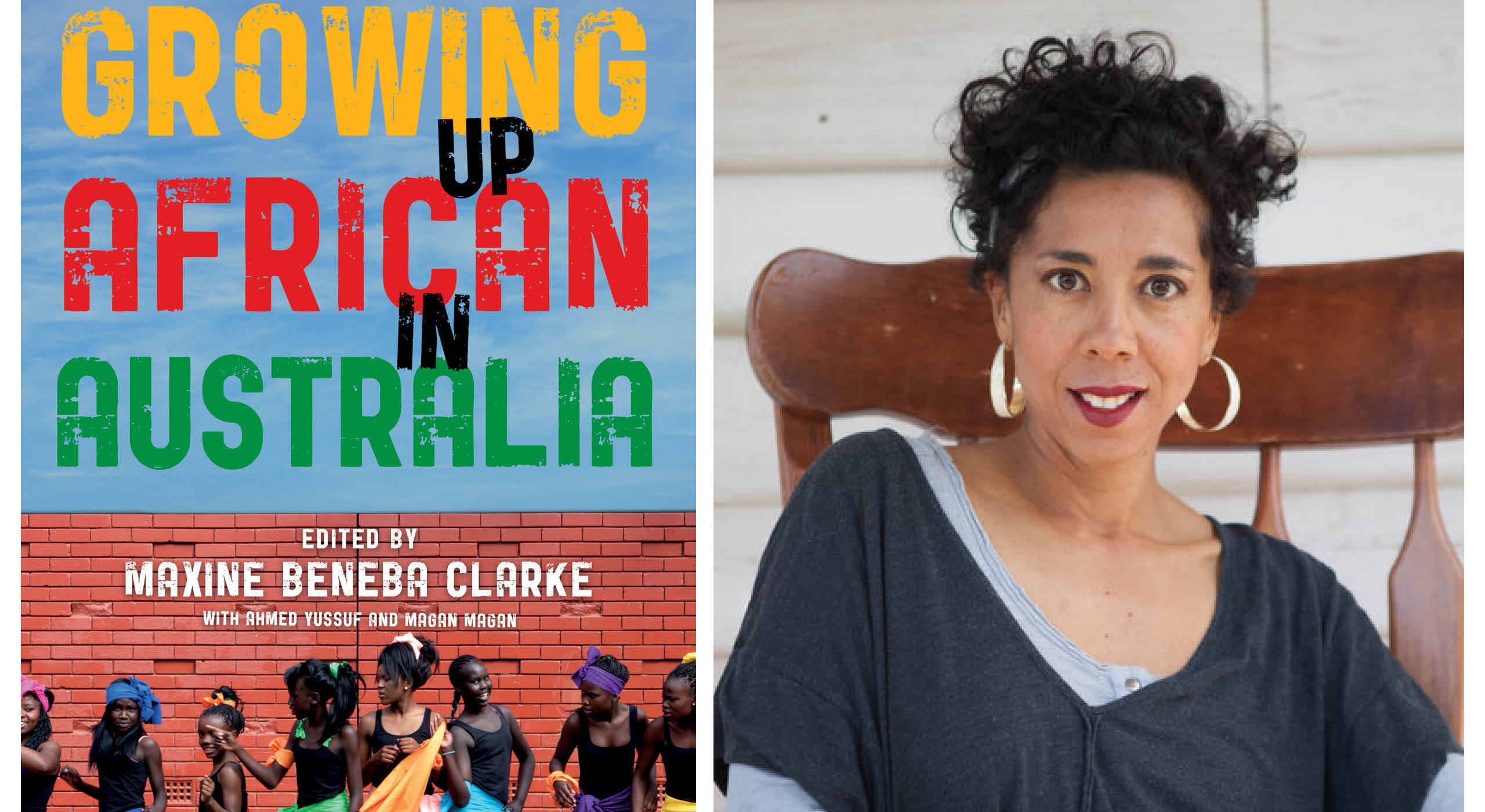

This is an edited extract from Growing Up African In Australia, edited by Maxine Beneba Clarke, published by Black Inc, $29.99

No Comments