Anna Sorokin understood the power of a carefully choreographed outfit. On her final day in court – after being convicted of grand larceny for defrauding New York’s wealthy elite – the 27 year old wore a high-necked, black babydoll dress and thick, black glasses that framed her heart-shaped face.

It was the latest in a procession of designer looks – all chosen by a Hollywood stylist – and the overall effect was chaste and contrite.

As Sorokin was led out of the court, she glanced across the room at the assembled photographers, and they captured her strained and mournful expression. Just as she knew they would.

After all, this was a woman who had manipulated some of New York’s wealthiest and most powerful people in a scam so lengthy, and so outrageous that not one, but two, movies are now in the works.

It all began in 2014 when Sorokin arrived in the United States, and assumed the identity of a German heiress. Using the name “Anna Delvey”, she presented herself as an art collector who planned to open a members-only art foundation in New York.

It was a convincing act. Sorokin lived in one luxury hotel after another, and dressed the part in Alexander Wang, Dior and Celine. She hired private jets, ate at expensive restaurants, and mixed with socialites, fashion types and minor celebrities like Macaulay Culkin. She even managed to inveigle her way into meetings with business heavyweights like Andres Balazs, the hotelier behind the Chateau Marmont and London’s Chiltern Firehouse.

The only problem was that none of it was true. The real Anna Sorokin had enjoyed a modest upbringing in Russia and then Germany, before moving to France and the US. She had no inheritance (her father owns a heating-and-cooling business near Cologne) and by 2017 she owed hundreds of thousands of dollars to hotels, a private jet company and several banks.

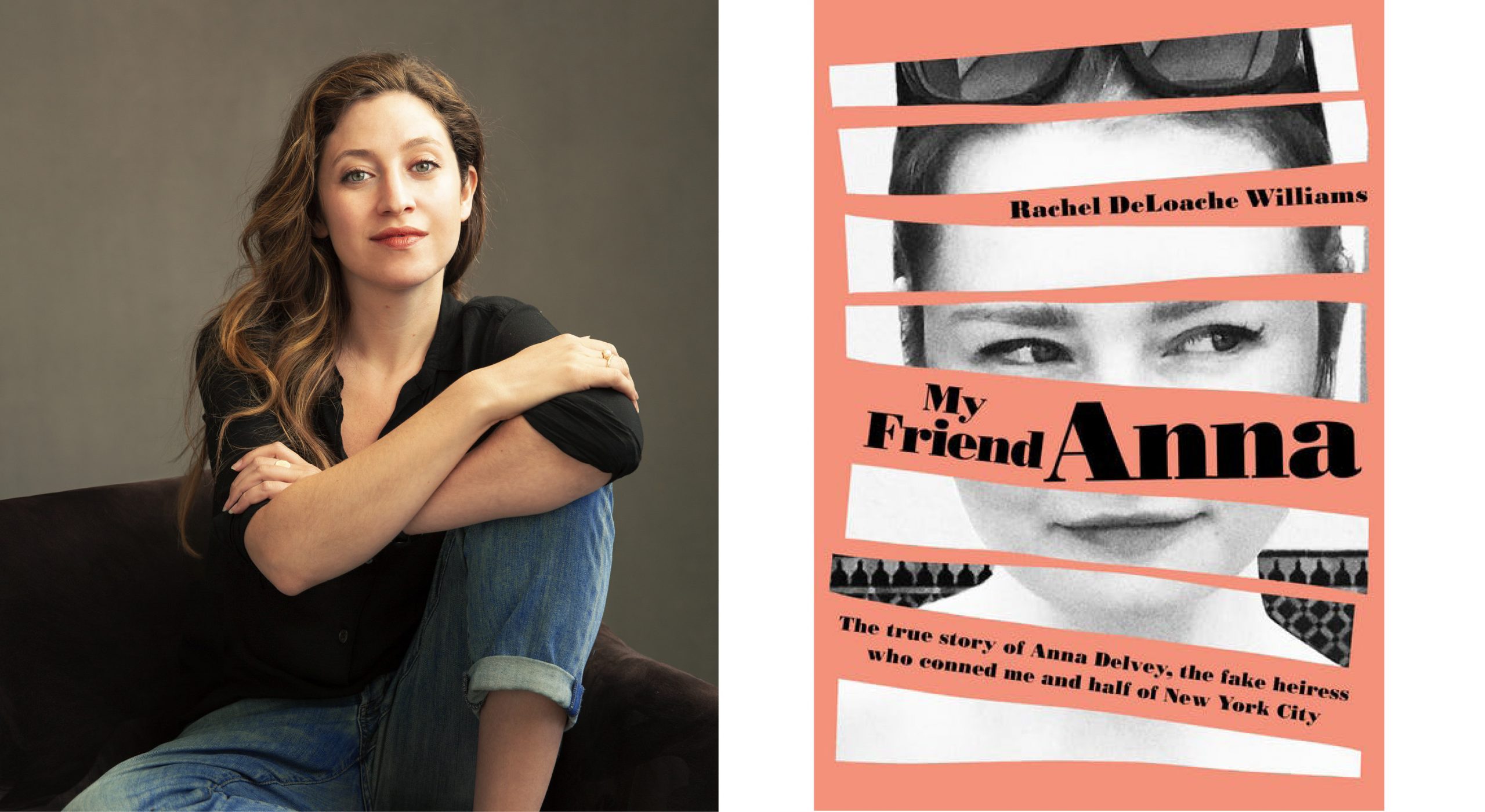

Eventually, Sorkin’s story unspooled as hotels and friends grew suspicious of her habit of borrowing large sums of money, and then failing to pay it back. One of those friends was Rachel De Loache Williams, then a photo editor at Vanity Fair, who found herself swept up in Sorokin’s lavish lifestyle, and ended up footing the bill for an expensive Moroccan holiday.

Here, Rachel, who was instrumental in the arrest of Sorokin and who has written a book, tells her story.

I can’t remember what arrived first: the bucket of ice with a bottle of Grey Goose vodka or “Anna Delvey”. She was a stranger, and yet not entirely unknown to me. I’d noticed her for the first time one month earlier, tagged in Instagram photos. Curious about the unfamiliar face, I’d clicked the tag over her image and discovered that @annadelvey (since changed to @theannadelvey) had more than 40,000 followers. After scrolling through her posts – pictures of travel, art and a few doe-eyed selfies – I assumed that she was a socialite.

In a clingy black dress and flat black Gucci T-strap sandals with gold bamboo-inspired accents around the ankle, Anna slid into the banquette on the other side of my friend Mariella. She methodically smoothed her long auburn hair, arranging it over her shoulders, as Mariella introduced us. Anna had a cherubic face with oversize blue eyes and pouty lips. She greeted me in an ambiguously accented voice that was unexpectedly high-pitched.

Conversation rolled along just fine, as did the cocktails. The evening had a distinct New York glamour to it – martinis in a steak house, chatting about our workday.

Anna had spent the day in meetings with lawyers, she said. She was hard at work on her foundation – a visual-arts centre dedicated to contemporary art, she explained, referring vaguely to a family trust.

I was impressed. Anna’s ambitions were remarkable – her plans were grand and promising in theory – but what was just as fascinating, if not more so, was her hypnotising manner. She was kooky, not polished or prim. Her hair was wispy, her face was naked, and she was constantly fidgeting with her hands. She was a zillion miles away from the debutantes I’d known in my youth, and I liked her more because of it.

As the months went on, Anna was in touch with me independently from the rest of the group. I was flattered she had singled me out, and we started getting together on occasion just the two of us. Over time, Anna and I became inseparable. The world was charmed when she was around – the normal rules didn’t seem to apply. Her lifestyle was full of convenience, and its easy materialism was seductive.

The power dynamic in my relationship with Anna evolved in such a way that I was oblivious to its strangeness. The activities we did at the start of our friendship involved expenses that I could afford. I assumed I’d pay my share. Anna would sometimes insist on paying for us both, but I’d return the favour on occasion.

The only problem was that Anna’s taste grew increasingly expensive. She started in the shallow end and swam out fast. She invested in her appearance as if it were a business expense. She went to Christian Zamora for $400 full eyelash extensions, or $140 touch-ups here and there. She went to Marie Robinson Salon for $400 colour and Sally Hershberger for $200 cuts. She wanted to try everything: cryotherapy, microcurrent facials, beauty-boosting IV drips, and on and on. When it came to material possessions, Anna was pared down, but when it came to indulgent experiences, she couldn’t get enough.

Since Anna liked to have company, she pulled me into the deeper water with her, where I knew my way around (thanks to my job at Vanity Fair and past experiences with wealthy college friends) but was not capable of floating on my own. Anna knew this. Yet, wanting what she wanted, she set our course and kept me on her raft. And I let her.

The vacation was Anna’s idea. She suggested Marrakech – she’d always wanted to go – and knowing that it was, in her words, “the hot spot”, she chose the hotel La Mamounia, a five-star luxury resort ranked among the best in the world.

Four days after announcing that she wanted to go away, Anna reserved a $7,500-per-night private riad and forwarded me the confirmation email. This did not seem preposterous – after all, Anna lived in one five-star hotel after the other. And at the time, I fully expected to pay for my own flights and expenses.

But midway into the trip, it became clear there was an issue with the debit card Anna had given the hotel to pay for our stay and, despite pressure from the management, she still hadn’t fixed the problem. The hotel made it very clear that they needed to have a functioning card on file, but Anna answered their entreaties with condescension and anger.

In Marrakesh, seeing no alternative, I buckled under the pressure, unzipping my travel pouch and removing my personal credit card. A manager stepped forward to take it. “The block will only be temporary,” he assured me.

But later in the day, when my card was refused I called American Express. I was told the hotel had put the payment through – $30,865.79. My vital organs shut down, caught fire, and floated to the top of my chest.

No, no I assured him, that was only a ‘block’ – it would not stay on my account. The duress in my voice must have registered. Instead of belabouring the fine points, he asked how much money I’d need to get safely out of Morocco. If it had been possible I’d have hugged him through the phone. He raised my spending limit, and I hung up.

At this point, I thought that Anna would pay the hotel bill when she checked out – and, worst case scenario, if the charge on my personal card were to stay there (without a credit for the same amount, as the hotel promised), Anna would repay me the following week when she wired reimbursement for the flights and expenses from outside the hotel.

This was not an arrangement I had agreed to in advance, but considering the way things had played out, it felt as though I had no choice but to go along with it. Anna was just a rich girl disconnected from the mundane stressors of monthly billing cycles; who’d gone on an expensive vacation and not told her parents; who’d blown through her allowance and been forced to stall for time; who’d backed herself into a corner but could easily sort things out. And I trusted that she would. I believed in her.

The following day, after having parted ways (as planned, I was going on to the South of France; Anna was staying on in Morocco), I texted her.

Just hoping we can get the wire etc sorted today because I’m nervous about my cards not working for the weekend. Sorry to be a bother.

It seemed like a foregone conclusion that the entire hotel bill would be on my credit card. We were both already gone from La Mamounia, but I trusted Anna to reimburse me as she’d promised. What else could I do?

I’ll wire you 70,000 [USD], that way everything’s covered, she wrote.

That was more money than I made in a year.

Thank you so much, Anna, I replied.

The wire with my reimbursement had been initiated, Anna said; I only needed to wait.

At ten o’clock the next morning, my phone buzzed with a text from Anna. Hope you are good, she said. Will make sure the wire gets settled today. She chimed in with an update before I’d even asked. Thank you, I replied.

The day ended just as it began, with a series of text messages from Anna.

One: Hey.

Two: All good?

Three: Let me know once you see the wire from your side. Hope it didn’t cause you too much trouble this weekend.

I checked my bank account. Nothing.

Two nights later, unable to sleep, I checked my bank account for any sign of an incoming wire. Then I logged in to American Express. The La Mamounia charges were still on my account, now totalling $36,010.09. And there were new charges, this time to my Condé Nast corporate card – two lines from La Mamounia, which totalled $16,770.45. It was the balance of our bill, an amount the hotel had been unable to put on my now frozen personal card. Evidently, they’d kept my corporate card on file.

My stomach did a somersault.

If I received Anna’s wire promptly, I could put the money towards payment of my corporate statement before anyone noticed. And yet, Anna was becoming increasingly unreliable.

I flew from Marseille to New York via Paris. Text messaging with Anna about repayment had become part of a new routine. We took turns starting the conversation each morning.

Sometimes I’d go first: Hi A, the wire still hasn’t come through. Do you have that ref so I can call chase to check on the status?

On other days, she’d beat me to it: Do you see the incoming wire in your account? Still waiting on remittance letters that I’ll forward you once i get it. If the wire still hasn’t arrived, your banker can use it to track it.

The delay weighed on my nerves but, since I had faith the funds would arrive any minute, I didn’t tell anyone about it. If I were Anna, I’d have been embarrassed to put such a strain on a friend. By not blabbing about it to others, I was being respectful.

Besides, I thought I understood Anna better than anyone else, so there wasn’t much point in asking for outside input. I rationalised her delay. Where logistics were concerned, Anna was ill-equipped, but somehow, it always worked out. The same principle applied to sending a wire transfer. She set the plan in motion, and even if it took a while – and she couldn’t find the reference number – I was sure the rest would fall into place.

When this was finally over, I would want space. Still, for now, it seemed wiser to lean into my relationship with Anna than to pull away, at least until the reimbursement arrived. We continued communicating, mostly through text messaging and, occasionally, by phone. When we weren’t discussing the wire transfer, we spoke as though nothing had changed.

But as the days went by, my texts to Anna grew increasingly desperate. Hey lady, do you really think the wire will come through today? I need to mail my rent. Could you do quick pay for 2k so that I can send a rent cheque w/o it bouncing? … My Amex bills are also due, but they can wait until Monday.

As the days went by, my texts to Anna grew increasingly desperate

Me: I’m really losing sleep over this. So sick to my stomach. This must post to my account this morning or something is seriously wrong.

Anna: No problem, I understand it’s no fun being in this situation, and I caused it, you have all reasons to be upset.

It was comforting to hear her claim responsibility for the circumstances. She validated my feelings and made me think she understood them by acknowledging I had good reason to be upset. For an hour or two, I felt lighter. But by lunchtime, my fear had resumed.

Another Monday came and went and still there was nothing – no wire, no cash and no clear explanation.

I texted: Anna – this is so urgent and has been for so long!! We need to make a plan to meet for the cash deposit today. I can’t keep waiting for this wire. I’m extremely stressed about this.

I threatened legal action, but she batted it away.

I threatened legal action, but she batted it away

Back in New York, on Thursday, June 22 – one month and two days since I’d left Morocco – unannounced, I walked into her hotel at quarter to eleven.

It was the first time I’d seen her since La Mamounia. She looked dishevelled, her hair matted from sleep. Her small bedroom was full and messy. Her suitcases lay open and overflowing.

“Where’s the cheque?” I asked, trying to make the transaction simple. She shuffled through piles of papers, looked under clothing, and dumped out various bags before claiming to have left it in a car.

Of course it couldn’t be easy. Of course there was a problem.

First she called the car dealership, and then her lawyer’s office. (“He must have it,” Anna proclaimed.) I refused to leave. Anna assured me that the cheque would be dropped off.

First she said it would be delivered to me at my office, but when she was unable to provide me with her lawyer’s cell-phone number, I decided not to leave her side. I shadowed her to a lunch meeting with a different lawyer, who was introducing her to a private wealth manager. I followed Anna back to the hotel. She told me that she needed to take a conference call.

“By all means,” I said, unmoved. “I’ll wait.”

She didn’t make a phone call. Instead, we sat side by side in the clubby bar beneath the hotel atrium. True to form, Anna ordered oysters and a bottle of white wine and signed the bill to her room.

I sat in silence, sending work emails from my phone, largely ignoring Anna but keeping a watchful eye on her and asking periodically for an update. Aside from our waiter, I didn’t see her interact with anyone. To prove a point, I stayed until 11pm, when I finally left, telling Anna that I would be back in the morning at 8am so that we could go together to the bank. She agreed.

“I hope you had fun, at least,” she chirped, with an impish grin.

“No, this was not fun. This is not OK,” I stammered, incredulous.

My problem with Anna was only getting worse. When I threatened legal action, I hoped to instil a sense of urgency – but she batted away the threat as though it were nothing.

It was more than two months since I’d left Morocco. I emailed the prosecutor from the DA’s office. If possible I’d really like to speak with someone today. I think this girl is a con artist. I can be available any time. I gathered as much information as I could in a folder I named Operation Clarity. I had a scan of Anna’s passport and an image of her debit card from when I booked the flights to Morocco.

My cell phone rang. The caller ID read, “United States”. I answered as I stepped away from my desk. “We think you’re right,” a voice said. It was an assistant district attorney from the Manhattan DA’s office, who confirmed that Anna Sorokin (aka “Anna Delvey”) was the subject of an ongoing criminal investigation. They wanted me to come in.

This is an edited extract from My Friend Anna: the True Story of the Fake Heiress of New York City, by Rachel DeLoache Williams (RRP $32.99, Hachette Australia), out now.

3 Comments