It’s been years since I worked in a corporate office but I can vividly recall the existential crisis dressing for casual Fridays invariably triggered. At the time I was 24, working as a junior lawyer in a big shiny law firm in Sydney’s Circular Quay.

Monday through Thursday, I rarely gave much thought to what I wore, thanks to the rigid corporate dress code. On Fridays, however, we were free to mix it up within the bounds of ‘smart-casual in a professional setting’.

And each Friday morning that vague description would send me into a spiral. I would pull out item after item in an attempt to find some combination that would satisfy all the criteria in my head, angrily discarding them one by one because they all looked and felt wrong. I usually enjoyed clothes, but I hated those mornings viscerally, not least because I couldn’t quite understand why I was behaving in this way.

Why did it matter? Why did I care?

Why did it matter? Why did I care?

The strange phenomena of a woman having a wardrobe full of clothes with nothing to wear is hardly a worthy crisis – I knew that even then – but what I didn’t appreciate was that the battle I was waging on those dreaded mornings wasn’t superficial. In fact, my paralysis was triggered by the fact it was the only day of the week where I had some leeway to express myself. This was completely overwhelming, because I didn’t know who I was. All I knew was that I needed to look a certain way, and no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t achieve it.

At the time I struggled to fathom why or how this seemingly straightforward task – picking an outfit – caused me to disintegrate so badly. The reason, I learned later, was that I was trapped in the toxic clutch of perfectionism. It proved disastrous.

Perfectionism was one of the reasons that a few months after my 25th birthday I was admitted to a psychiatric facility. I had spent the preceding four months living back with my parents in northern NSW, effectively unemployed. My physical and mental health had eroded to the point I was barely able to function let alone participate in life. I suffered a total nervous breakdown.

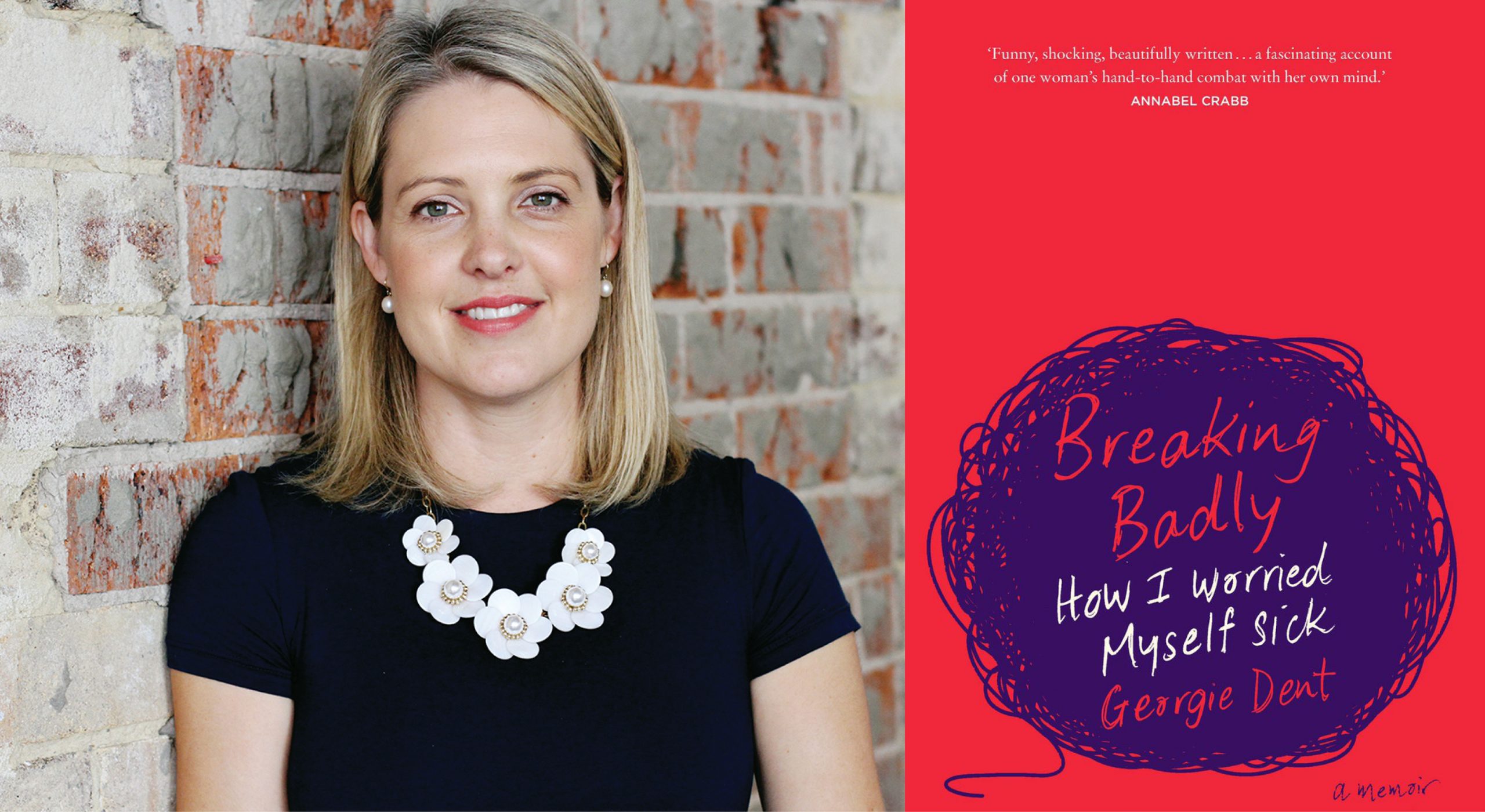

It became a landmark in my life that I couldn’t – and didn’t want to – forget. Recently, I wrote a book, Breaking Badly, about the experience and what I learned from it.

What I came to realise what that my breakdown didn’t happen because I had a traumatic childhood, suffered abuse or endured anything truly ghastly. With the exception of Crohn’s disease, which can’t aptly be described as a stroke of luck, my hand in life was more notable for its abundance of good fortune. I didn’t fall apart because I had a nasty auto-immune condition or because I worked around the clock or because I was a natural-born worrier. I didn’t fall apart because I developed anxiety. I fell apart and suffered a breakdown because I did not cut myself a break. Ever. About anything. Not about my health, not about my work – not even about what I wore on casual Fridays. The consequences of this toxic habit cumulated over time and were eventually devastating: I unravelled physically, mentally and emotionally because of it.

Knowing that I was lucky and privileged only proved to be corrosive. I believed that because I had been lucky in many of life’s lotteries, I had no justification for struggling or suffering.

I was a natural-born worrier. For as long as I could remember, I had been permanently preoccupied with worries – big, small, highly likely and entirely fanciful. For me, worrying was the rule rather than the exception, and if I ever caught myself without an active worry, I immediately began worrying about whatever it was I had temporarily forgotten to worry about.

For me, worrying was the rule rather than the exception

As a child I worried that my parents would separate, that my dad would die, that my mum would have an affair and that robbers would break in and kidnap my sister and me while we were sleeping. I worried that my little brother would get sick, that a car accident would kill my whole family and that Dad would lose his job, even though he had his own business, so effectively worked for himself. I worried that snakes or spiders or dogs were lurking, ready to attack at the first opportunity. I was convinced that all white vans were driven by violent fiends who would lure children from schools with lollies before taking off with them.

These were not special-occasion concerns: these fears, and many more manifestations, formed the silent soundtrack to my life. I cannot recall a time when my mind wasn’t quietly consumed with the vague sense that disaster was imminent. Every film I watched fed my young mind a host of new concerns: I would physically recoil at the idea of a character being hurt, getting lost, being lied to, or suffering any fate that wasn’t wholly comfortable and secure. Since comfortable, secure stories hardly lend themselves to dramatic interpretation, movie-watching was always fraught.

I was also a perfectionist. At school and at university I had always been determined to do well, even without external pressure. I didn’t have the weight of anyone else’s expectations bearing down on me, and yet I was uncompromising in wielding my own unrealistic expectations over myself. I believed that if I didn’t do well, if I failed at something, I would give people a reason to judge me. Doing well was a form of self-protection.

I was uncompromising in wielding my own unrealistic expectations over myself

Years later, I learned about how the toxic tentacles of perfectionism take hold, and it proved revelatory. As the author and researcher Brené Brown writes: ‘Perfectionism is not the same thing as striving to be your best. Perfectionism is the belief that if we live perfect, look perfect, and act perfect, we can minimise or avoid the pain of blame, judgement, and shame. It’s a shield. It’s a twenty- ton shield that we lug around thinking it will protect us when, in fact, it’s the thing that’s really preventing us from flight.’

My own enlightenment came in the form of a workshop on perfectionism run by Victoria, a psychologist I’d come to know because of the group therapy sessions she ran at the facility where I was an inpatient.

‘We are going to explore perfectionism today, and before we begin I want to get a sense from you about how it might be impacting each of you,’ she said to kick things off.

‘Put your hand up if you have ever felt like nothing you do is good enough,’ Victoria asked.

I practically snorted, inadvertently, as I shot up my hand. Several other hands went up too.

Victoria looked at me with a smile. ‘Georgie, my question obviously struck something in you. When can you remember feeling that way?’

‘My whole life. I have literally never not felt that way.’

A man in his forties laughed. ‘Me too,’ he said.

‘That’s not an unusual response in here,’ Victoria said.

‘Perfectionism is a pervasive risk factor for depression and anxiety, so it’s an issue for many patients.’ Clinical perfectionism, she explained, is described as relentlessly striving for high achievements and unfairly judging yourself when those goals can’t be met. ‘For perfectionists,’ she went on, ‘life is an endless report card, and anything less than an A+ is a failure. And the trouble is no one ever gets A+ for everything, and life isn’t a subject at school. Failure in some form or another is inevitable. But for perfectionists, falling short, even in little ways, can feel catastrophic.’

To say I related is an understatement.

I had always thought ‘I’m a perfectionist’ was a humblebrag: shorthand for ‘I have impeccably high standards’, ‘I work hard’, ‘I pursue excellence’. Why else was it relied upon so often in response to that age-old interview question: What are your weaknesses?

I had always thought ‘I’m a perfectionist’ was a humblebrag

In recruitment, I had learned, framing a penchant for details and excellent results as a ‘flaw’ ticked a few boxes: it lets you recognise your own ‘shortcomings’ while leaving the impression you were driven and focused. Personally, I used it on several occasions, and while it may have helped land me a few jobs, in rehab I learned the joke was on me.

Perfectionism was my paradigm.

‘One of the reasons perfectionism is toxic is because ultimately it’s about seeking the approval of others,’ Victoria said. ‘It’s about measuring up, but perfectionists rarely concede that they do measure up.’

The penny dropped. Being ‘perfect’ was the armour I sought out to protect myself from falling short. I was living at the mercy of what I imagined ‘other people’ thought, and not because I was particularly invested in the views of any person in particular. I was terrified of being judged by anyone about anything.

Recognising this was, strangely, liberating because it exposed how utterly unsustainable my pursuit of perfectionism was. No achievement – and certainly no outfit – was ever going to be good enough.

The irony that my relentless pursuit of perfection landed me in the decidedly “un-perfect” confines of a psychiatric facility was not lost on me. Hitting rock bottom, however, was a blessing in that it delivered clarity and perspective that enabled me to ditch perfectionism and embrace good instead.

Georgie’s tips for ditching perfectionism:

No Comments