Few authors would consider themselves lucky to be releasing a book in the midst of a global pandemic.

Laura Jean McKay might be the only exception.

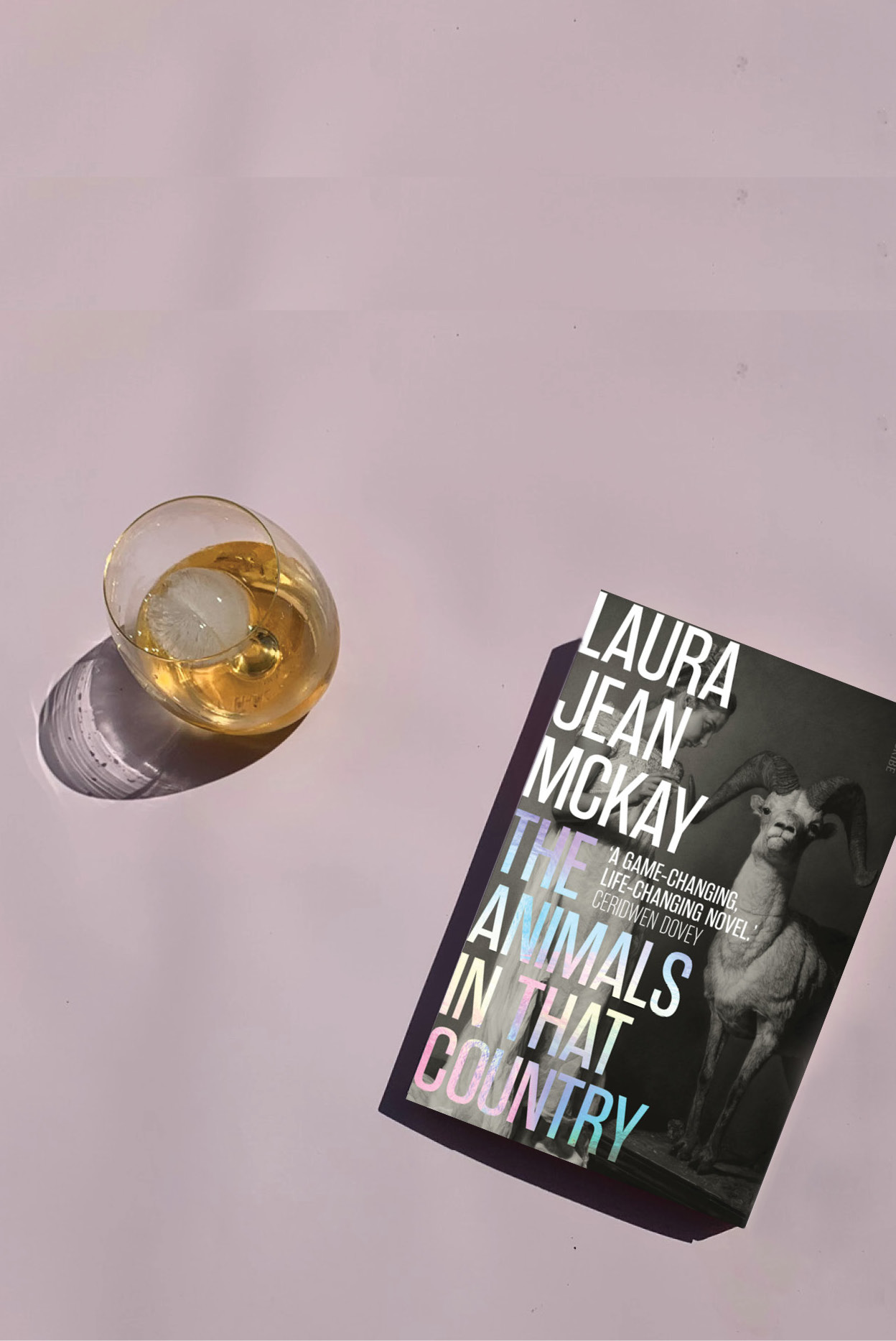

Her novel The Animals In That Country centres on the outbreak of a highly infections subtype of influenza that threatens the very fabric of society. (Sound familiar?)

It’s an eerily prescient premise, right down to the conspiracy theories that proliferate on Facebook and the government ads that encourage people to “keep calm and stay indoors”.

The story is told through the eyes of Jean, a no-nonsense, foul-mouthed grandmother who works in a remote wildlife park. Jean struggles to keep her alcoholism under control, and feels more affinity for the animals in her care than for the people who visit them. The only thing that tethers her to the routine of life is her granddaughter, Kimberly — a six year old with dreams of opening an animal park of her very own someday.

The action starts with a spike in incidents of ‘eco-terrorism’ down south, with activists releasing animals from zoos and farms en masse. There’s an outbreak of a new strain of influenza. At first, the problems seem unrelated, until the stories start to merge…

It turns out that this flu – this “zooflu” – gives the afflicted the ability to communicate with animals — and what the animals have to say is sending them mad.

As the story unfolds, Kimberly’s estranged (and now infected) father reappears, and abducts the child with a view to taking her down to the southern coast to communicate with migrating whales. Jean has no choice but to follow them in a beat-up caravan, with Sue the dingo riding shotgun to herd her pack back together.

Most animal lovers might suppose that being able to talk to their furry companions would be a dream come true, but this book is a long way from childhood fantasies and Charlotte’s Web. McKay has written a searing dystopian critique of our relationship with the natural world. In fact, the book’s title is taken from a collection of poetry by Margaret Atwood published in 1968, one that leaned heavily on themes of environmentalism and social justice.

Through poetic projections of what the animals might say if they could, McKay highlights our limited capacity to communicate with language, and our human-centric view of the natural order. What would happen if animals suddenly had the agency to tell us what they thought about the current state of affairs? In The Animals In That Country, it’s not a philosophical question, it’s an apocalyptic reality.

The current real-life crisis has —understandably— led to a resurgence of ‘escapist’ literature, light-hearted and lovely stories to take our minds off things.

The Animals In That Country certainly doesn’t fall into that camp.

Earthy, visceral, at-times obscene and all-too-real, The Animals In That Country is nevertheless compelling and oddly buoying.

McKay is a masterful storyteller, and her talent truly shines in this quest for family and belonging. Reading it reminded me that opportunity can arise from hardship, and reignited my hope that some good might come of it all.

No Comments