One Monday night a few years ago, I found myself walking to a Sex Addicts Anonymous meeting in Sydney’s Surry Hills. I didn’t know who I’d meet or if I’d be safe. When I stepped into the meeting room, I saw a group of nine or 10 men, sitting in a circle on plastic chairs. The facilitator, a man, smiled and welcomed me to take a seat in the circle.

Behind him, The Twelve Steps guide hung as a poster.

The facilitator asked us to go around the circle, say our names, and detail any sexual activities we’d engaged in during the past week. I sat there, fingernails digging into the flesh of my fingers, heart hammering so hard against my chest I thought my body would explode. When it was my turn, I told everyone my name, and then politely declined to say anything.

I was so relieved when the facilitator said that was okay. I stayed for another half an hour. Then I left. I was the only woman there, and I felt like the alcohol at an AA’s meeting. I was terrified.

How did I find myself in such a bizarre and intimidating situation?

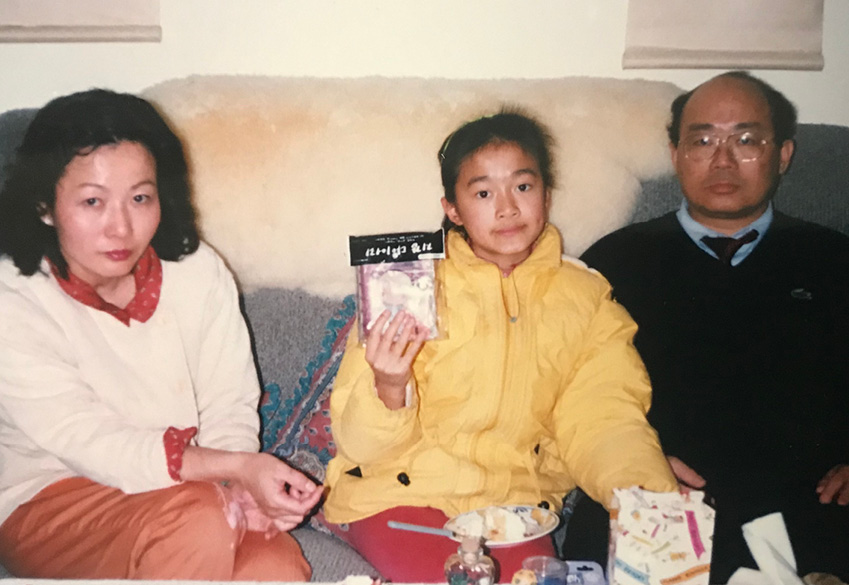

Looking back, I can see that my upbringing played a crucial role in my struggles with my sexuality. I grew up in a strict conservative Asian household where sex, dating and boys were vigorously discouraged. Sensuality, sexuality and sexual expression were taboo. I was the youngest of four children, and the youngest of three daughters. We had a 6pm curfew. I was not allowed to go out with friends, to go to the cinemas, to ‘hang out’.

What does that do to you? As a young girl, what does that leave you with? And how does that influence the way you think about sex?

It made me feel ineligible for love, and for many other things that my white Australian friends were given access to, including liberty of their body, which I never had, until I moved out of home.

My conservative upbringing had profound psychological effect on me. My parents loved me so viciously that their love seemed to me more like a chain, a handcuff, than ‘protection’.

There was one particular incident that stands out in my mind. When I was 18, I brought home my best friend. He was a boy. We had no sexual relationship.

That afternoon, we dumped our bags in my room and emerged moments later to take our bikes out for a ride. My father was home early. When he saw us, his posture stiffened, and he looked disgusted. I felt his anger sear through me, my small body taking in his body as a visual weapon of threat. I stood still and I received it.

My friend walked to my father and extended a hand. My father stood like a statue, his arms erect by his side. He simply stared at me with that look of distaste, then turned his back to us, and walked inside the house. My friend shrugged, then told me he wasn’t offended.

Weeks later, when my father had calmed down, I asked him why he had been so angry that afternoon. “Men only want one thing from you and you better know by now what that is,” he said. “When you give yourself to a man, you are ruined.” Was this the way he was taught to understand sex and love? That it was the boy who took something from the girl?

I often think back to that moment, and how such a violent denial of my personal freedom might have affected me, and how that feels now, as an adult; how that might have led to my voracious hunger for it as a young adult.

A few years later, I moved out at 22, and it was a battle. My parents were hurt that I’d leave the family home without being engaged to a man. My sisters moved out of home only once they got married, and my parents expected me to do the same.

But I didn’t want to wait for that. I couldn’t. After I became financially independent, I had to move out. I had to find my own independence.

I began dating. Quickly, I found myself sleeping with multiple men at once. Since I previously had no freedom over my own body, I became reckless with where I took it, who I consummated it with, who I’d let take it.

I was careless with my safety.

I hiked alone in New Zealand. I travelled to Yemen and Palestine. Perhaps, simply because I could. I think I wanted so badly to retaliate for all the physical solitary confinement that restricted me as a child.

When you grow up in a family where sex is shameful, you form strange ideas, unhealthy ideas, about it. I began to only associate sex with being loved, and reached for it as the only way to feel loved. I’d sleep with a man on the first date, believing that if I didn’t, he wouldn’t be interested in me. I thought about sex a lot because I was denied full expression and agency of it for so long and I was reckless with the way I deployed it with men.

A few years ago, I fell into an abusive relationship with a man who used my body as a way to curb his own feelings of loneliness and insecurity. He was manipulative and violent, and I remember, on more than one occasion, thinking to myself “I could die”. And yet I stayed.

I managed to leave, only after an especially terrifying incident where I came close to losing my life. My brother and I spoke on the phone afterwards, and after I told him what had happened, he said the words I couldn’t tell myself, “Leave. You need to leave. Or you might actually die.”

I came home alone from the trip and sought sex therapy as a way to protect myself. I wanted a way to confront the trauma I’d faced, and ensure I never put myself in such a situation again. I wanted a way to make sure I could still be open to being in a relationship with a man, without putting myself at risk.

Although I never returned to group therapy, I found success with one-to-one counselling. It remains one of the most life-affirming things I’ve ever done. I was able to talk about sex in a comfortable environment (my therapist is a woman) and unpack many ideas and feelings I had about it. I’m still someone who is deeply interested in sex, but I don’t reach for it as unthinkingly as I used to. I haven’t resolved all of my feelings about it, and I’d never want to reach a place of resolve, because that’s impossible, but I am more confident that I can now protect myself against the dangerous situations I used to put myself in.

My parents and I are now extremely close. It’s taken most of my life to reach this place of love and comfort, but we are all much more accepting of who we are than we used to. I’m grateful for the journey therapy has taken me on. And I continue to take this journey, for as long as I live. Therapy is not only for a small cohort in society. I think everyone would benefit from what it provides: a safe, professional space to let out the messiness inside our heads. To lift the veil over which many of us walk around in our lives, and examine what’s really within us. What’s in our hearts.

Jessie Tu is the author of A Lonely Girl Is A Dangerous Thing (Allen & Unwin)

No Comments