Ten years ago, I was 29 and at a turning point in my life. I had my first full-year contract as a creative writing academic in Melbourne. Admittedly, this doesn’t sound very stable but compared with having to reapply for sessional lecturing positions every semester, it seemed like success.

I was also about to get married to a very lovely person with a demanding (and much better paid) career of his own. Because my office hours were shorter, I tended to do all the housework. Because his work was based in Melbourne, I didn’t apply for positions at universities interstate or overseas. These were my choices, and I was happy with them, I believed then.

It was at this time that I picked up a copy of My Brilliant Career. Having grown up in Aotearoa, I knew little about the author Miles Franklin.

Her name was familiar from Australia’s two biggest fiction prizes (the Miles Franklin Award and the Stella Prize). Her severe expression was familiar from that iconic image of her in a tight corset, long black plait down her back. Otherwise, I knew nothing.

As I read her autobiographical novel, published back in 1901 and written when she was still a teenager, I became fascinated. The “firebrand” narrator, Sybylla (based on Stella herself) is tempted by the conventional path of marriage but ends up rejecting it in favour of becoming a writer. Her suitor Harold Beecham (played by Sam Neill in the film version) ends up marrying her younger sister, Gertie, instead.

Sybylla tries to feel happy for her sister, but her predominant emotion seems to be pity. She pities her “pretty peacemaker” sister for choosing a life of self-sacrifice and drudgery.

As I read this, I had two thoughts. First, I thought that these sisters were like caricatures of two conflicting parts of myself (on the one hand I wanted to just write, on the other, I wanted to be a good wife).

Second, I wondered whether Stella Miles Franklin had a real sister on whom Gertie was based and, if so, how this sister would have felt being written about in this way.

I soon discovered that there was a real younger sister, Ida, nicknamed Linda. In the Mitchell Library in Sydney, I found letters between the sisters, which revealed that Linda had a witty and sarcastic writing style.

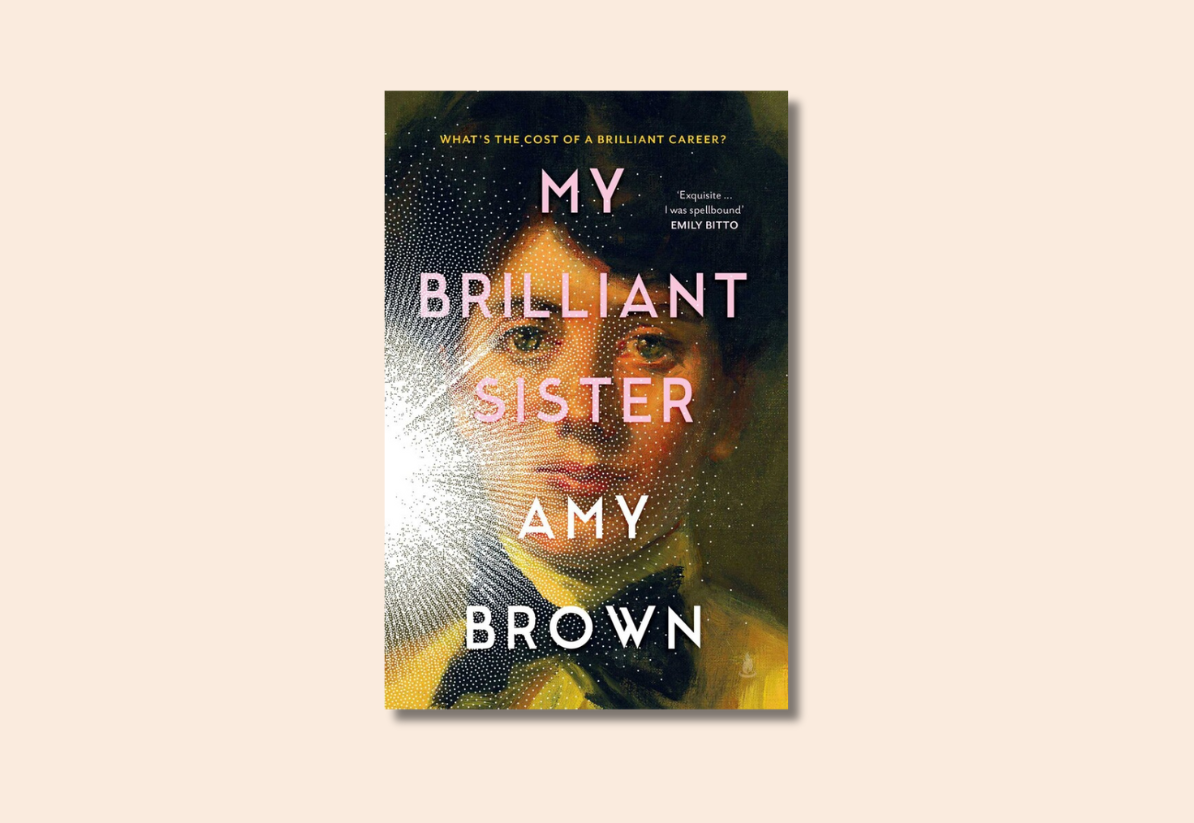

Why had one sister successfully pursued her dream as a writer while the other hadn’t? What if the only difference between the two women was a sense of entitlement? These questions wouldn’t leave me. Nor would Linda’s voice. So, I started to write Linda’s own version of events, which turned into the middle section of my novel, My Brilliant Sister.

As I learned that Linda Franklin married Charles Graham, the real-life Harold Beecham who had originally courted Stella, I married.

As I read that Linda gave birth to a son, I gave birth to a son.

As I read that Linda contracted pneumonia, I contracted pneumonia. I was run down according to the doctor, from caring for a baby and working as a high school teacher (having abandoned attempts at a career in academia).

The similarities between my life and Linda’s end there, due largely to the discovery of penicillin. Tragically, Linda died of her pneumonia aged 25, when her son was only one.

As I immersed myself in Linda’s life, I recognised that I was curtailing my career to try and be a good wife and mother. Options I might’ve chosen – for instance, to apply for academic jobs outside of Melbourne – I didn’t consider because I didn’t want to rupture my family life or impose on my husband’s career. Everyone has to make choices, I believed, while failing to admit that the choices I was making were influenced by patriarchal expectations.

I recognised that I was curtailing my career to try and be a good wife and mother.

It was Stella’s influence that I needed instead. As the antibiotics that were unavailable to Linda in 1905 gradually healed my lungs, the conversations I had with my husband (also unavailable to Linda in 1905) corrected our divisions of labour to the profound benefit of us both.

These kinds of conversation are not easy to raise – in fact, sometimes I found it easier to write a letter rather than to speak. Because he is a reasonable and understanding person, he listened, read, and responded. In our behaviours and priorities, we had blindly slipped into gendered roles that suited neither of us – reflected neither of our values. I was losing writing time; he was losing parenting time – resentment and stress was gathering on both sides. And so, we made some small yet essential changes.

Stella Franklin’s grandmother called her “froward”, a wonderfully old-fashioned word for difficult. It was meant as a criticism, but I choose to see it as a compliment now. A brilliant career is difficult – both to have and to live with. To pursue one, as a young woman (in 1901 and now), requires being difficult.

If there are multiple people in the same household trying to be brilliant, compromises and sacrifices obviously must be made, because in the background of the moments of brilliance are the countless acts of care. These small acts matter and keep life going, and therefore should be shared.

Amy Brown’s novel My Brilliant Sister is out now.

Enjoyed this story? Sign up to PRIMER’s (free) weekly newsletter to receive more just like it.

No Comments