It was high summer when I declared I was moving out. I’d woken in a room flooded with sunshine, lace curtains blowing in the sea breeze. We could hear the kids watching cartoons and eating Coco Pops in the next room, sun-burned and wearing the board shorts and rashies they’d slept in. For no apparent reason and without warning, I felt as clear as the blue sky. My heart was soft, my mind calm and I was certain. The constant stream of ‘what ifs’ that had roared inside my head like a siren non-stop for the past three years had suddenly fallen away.

I imagined this was what dying felt like. Transcendent.

‘Hey, Marz,’ I said, rolling onto the side of the bed, swinging my legs over and pulling on the sundress I’d left sprawled on the floor the night before. ‘When we get home, I’m moving out. We’ve tried everything a million times and we’re just getting sicker and sicker. There has to be something better than this. I’m exhausted. I surrender.’

The clarity of that moment was in stark contrast to the past three years of jagged pain, panic and confusion. My sudden resolution came from nowhere and everywhere. Like puzzle pieces falling into place. A lock and key. About bloody time and not a second too soon.

There has to be something better than this

We were in Cunjurong Point, a small beach town on the NSW South Coast, holidaying with mates as we had every January for the last few years. It was not going well.

Emotionally, we were both unwell. The pain of broken dreams is hard to contain, particularly when you’re exhausted by the effort of holding it together. Trying to repair yourself and your relationship while deciding whether to hold or fold and walk away is a Herculean task. Throw working and raising kids into the mix and you have a clusterfuck of extreme adulting.

I don’t know how people do it. I don’t know how we did it.

We were at our very worst doing our absolute best, which often looked like barely holding it together one day and totally dropping the ball the next.

***************

Cunjurong is a sleepy collection of fibro shacks, with no fences or footpaths, that hasn’t changed since the 1950s. I pushed the floaty white curtains aside and poked my head out the window. Teenagers wandered lazily down the middle of the road. Young parents loaded down with inflatable toys, nutritious snacks and all manner of potential solutions to possible problems trudged towards the glittering promise of the beach.

The parents looked as if they were wondering why the fuck they drank so much last night. They were already exhausted and it wasn’t even 9am. But they were determined to make holiday memories: otherwise, what the hell was all the work for? Wasn’t this meant to be fun? Wasn’t this why we had kids? I imagined them asking themselves. Later, there would be a moment of complete happiness and love, and their exhaustion, boredom and disappointment would evaporate. They’d capture this moment in a snap – and on seeing it, other friends would ask themselves, with a pinch of jealousy, ‘Why don’t we ever go on holidays like that? The kids would love it.’

We all propagate these myths: the innocent childhood, the happy family, the perfect couple, the dream job, the ideal life. But the truth is everything and everyone is breaking, all the time.

Perhaps these young parents were attempting to recreate the holidays of their own childhoods. Or maybe they had missed out on family vacations. Perhaps they, like Marz and I, hoped providing their children with idyllic beach trips would make them whole.

The drive home from Cunjurong was long, quiet and sad.

There was a sense of peace, though. We weren’t in a hurry to get home, because the task before us was so overwhelming. While we stayed in the car, we didn’t yet have to face the uncertainty and complexities of beginning our new lives.

***************

Marz and I had been together for 17 years. He was a loudmouth Catholic wog from Brunswick. I was a loudmouth Catholic bogan from Reservoir. It was a match made at Northland.

He was a photographer. I was a comedian and writer. We were living the ‘better life’ our Italian and Irish relatives had travelled on boats to Australia for.

Fourteen of the 17 years Marz and I spent together were pretty good. We were quite the double act. But suddenly niggly things – things that had always been there, things we’d tried to ignore and assumed we’d eventually fix or they’d go away – took over. Nothing corrodes a relationship more than resentment, and sometimes you reach a point of no return. I know – because I’ve been there. When that happens, you have to choose between staying miserable, self-medicating and dying of a broken heart, or making a run for it to save yourself.

We spent the last three years of our relationship doing absolutely everything we could to stay together: therapy, couples counselling, living separately, moving back in together, sleeping in separate bedrooms and having a stab at being Single People Parenting Under the Same Roof.

We were both smoking. I was barely eating.

Nothing corrodes a relationship more than resentment

Splitting up is exhausting, but staying in a dysfunctional relationship is like slowly drowning each other.

I indulged in some reckless behaviour: an affair that resulted in an abortion, a couple of pharmaceutically assisted threesomes, a visit to a swinger’s club and some fairly wild hook-ups. There was at least one episode of drink driving (which is incredibly out of character for me, because I don’t really drink), and some less than perfect parenting. I wasn’t abusive or neglectful to the kids, but I didn’t always live up to my own standards.

At times when I looked at my darling three little boys, I felt as if I was trapped in a glass box of pain, exhaustion and confusion. Their beauty and sweetness overwhelmed me. They might be rolling around on the trampoline, laughing and shrieking, slumped on the couch glued to the television, eating cereal and chatting on high stools at the breakfast bar in their pyjamas, bickering in the rear-vision mirror or lying in bed next to me, sleeping gently.

To see them but feel so far away from them was painful. I’d wanted children, I chose to have them, I loved them deeply. They were my responsibility, and they deserved better than what I was able to give at that time. I missed feeling connected, I longed to feel present. I was giving the boys all I could, but I couldn’t enjoy them the way I had in the past. I felt numb. I was on autopilot. They say they didn’t feel the distance – but I did.

It was as if I were being dragged out to sea and was trying desperately to swim back to them as they paddled in the shallows.

I was so preoccupied with the future – mine, ours, theirs – and working out the best way to create the least amount of damage moving forward that I missed many moments. Some simple, some important, others just moments I’d never get back.

Why did Marz and I work so hard for so long to keep the relationship going?

There were several reasons. We still had fondness for each other and a sense of loyalty. There was no guarantee we’d be happier if we split up. If you are in a relationship that is 95 per cent shit and 5 per cent good, you could leave it and end up alone, feeling 98 per cent shit and 2 per cent good. It’s a gamble.

We’d built a community, culture, life and language together. People knew us as a couple – Dev & Marz, Marz & Dev. We were part of other people’s lives and lore. We knew each other’s family, friends and past, had made a home together and created thousands of shared memories. We had woven our lives and selves together. It was like dismantling a corporation.

Then there was the practical issue of money. Marz and I had both grown up in poverty. We had worked hard to buy a house, renovate it and create a comfortable life for our boys. Neither of us had had a stable home ourselves as children and we wanted to make sure they did. More than anything, we didn’t want them to lose their home.

‘What about the children?’ is a question that goes through the minds of all parents breaking up, no matter how progressive they are. A voice in my head said, ‘You’ll wreck the boys. They’ll be heartbroken. Take drugs. Hate you. Drop out of school . . .’

I knew those things could happen anyway. I’d seen plenty of people from ‘good homes’ fuck up their lives. I’d also seen plenty of people from ‘broken homes’ have brilliant, meaningful lives and authentic, loving relationships. But ‘What about the children?’ runs deep. It’s tattooed on our psyches and no amount of evidence, experience or logic can override it.

As we went through the process of splitting up, I talked to a lot of people about the ‘What about the children?’ issue. I came to these two conclusions, which have been my parenting mantras ever since:

All children need is to know they are loved.

All children want is to see their parents trying – not always succeeding but trying – to get their shit together.

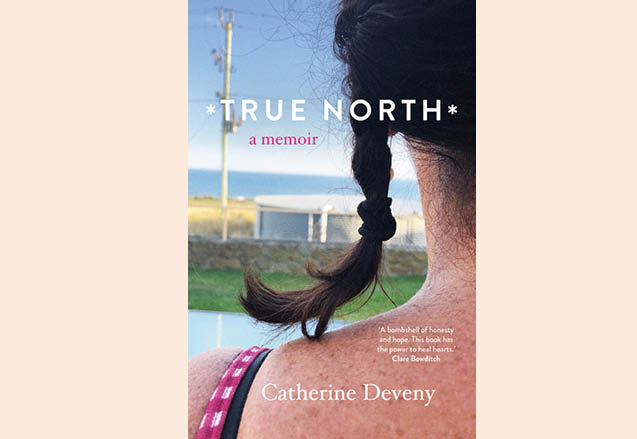

This is an edited extract of True North by Catherine Deveny, published by Black Inc, $29.99. It’s released this Tuesday, March 29

Photo credit (main): Brent Lukey

No Comments