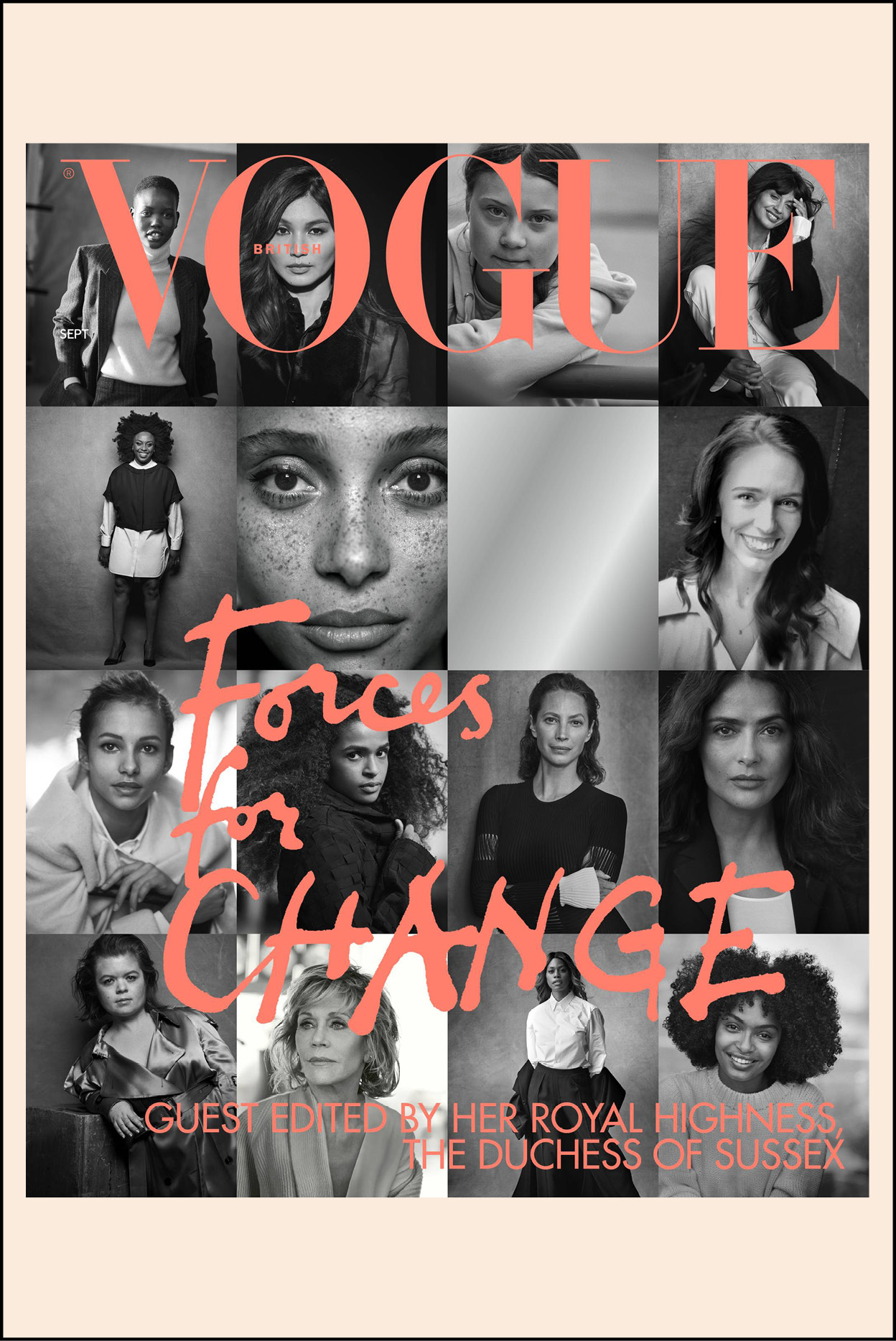

If anything illustrates the new cultural landscape, it’s the latest cover of British Vogue – particularly compared to the same September issue of 10 years ago. Back in the mists of 2009, the magazine hit stands with a cat-eyed Kate Moss on the cover, shot by Mario Testino. He’s since been outed in the #Me Too movement, and while Moss is famous for many things, a commitment to ethical causes isn’t one of them.

Today sees the release of a very different-looking magazine. Guest-edited by Meghan Markle, Vogue has an arresting monochrome cover that features a grid of 15 inspiring women – from teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg to 81-year-old Jane Fonda – who’ve been selected for their commitment to positive change. The 16th square has been left as mirrored foil for you, dear reader, to reflect upon your new #MeToo activism, or just to touch up your lippy.

Obviously, much has changed in the last 10 years, not least the popularity of print magazines. But the difference in covers starkly illustrates the way ‘good’ has become a new marker of style. From trainers to homewares, lipstick to loo roll, it’s not enough anymore for a product to simply look good – now it has to do good, too. Brands have recognised that many consumers care about the provenance of the stuff they buy and that, given the choice, those customers will take the ethical option.

In the US, for example, sales of sustainable products have increased by 20 per cent since 2014, while here in Australia there are now 20,000 social enterprises (like PRIMER), which are set up to deliver money and services that create change and give back.

‘Good’ has become a new marker of style

“We’re seeing a more conscious consumer who’s aware of the impact of mass consumerism on the planet,” says Afdhel Aziz, marketing guru and co-author of Why Good Is the New Cool: Market Like You Give A Damn (yes, we stole the title for this feature). A Good Is The New Cool conference takes place in Sydney and Melbourne in the next two weeks. “These consumers are more concerned about what they buy and how they buy it,” he adds.

But before we indulge in too much happy backslapping, this new trend for sustainability and ethical awareness isn’t without problems. Accusations of “greenwashing” are rife, as some companies spruik ethical credentials that aren’t quite deserved. Zara’s commitment to producing all its collections in 100 per cent sustainable materials is undoubtedly laudable, but the fact remains that it’s a fast-fashion brand that produces tens of millions of items every year.

As Keep Cup founder Abigail Forsyth said of fashion generally this week: “Businesses on the one hand are giving back [to charity], and on the other hand, they’ve got a six week cycle in the fashion industry and throw everything in the bin at the end of it… You can’t do bad with the left hand and good with the right. It won’t work.”

But is something better than nothing? “It’s depends on the intention,” says Tim Ferrier, consumer psychologist and co-founder of marketing agency Thinkerbell. “If a company is taking steps to move from bad to good, and they misfire along the way, at least they’re still on the journey.”

Zara’s commitment to producing all its collections in 100 per cent sustainable materials is undoubtedly laudable, but the fact remains that it’s a fast-fashion brand

As Instagram reminds us daily, that journey to sustainability is littered with good intentions. Being good is hard sometimes, and requires more beeswax wraps and Keep Cups than many of us ever thought necessary. And while ethical companies have always been around – shout out to The Body Shop and Stella McCartney, who’ve been pioneering sustainability and consumer activism long before it became fashionable – it’s only in the past few years that many brands have committed to more sustainable and ethical practices.

When Justine Flynn, her now-husband Daniel (below) and their friend Jarryd decided 11 years ago to start social enterprise Thankyou, a personal care and water company, they received what she politely describes as a “mixed response” to their plans. The idea was to establish a bottled water business that would deliver 100 per cent of profits to fund clean water projects. “The idea was pretty much unheard of at the time,” she says. “Friends, family, mentors and advisors – they all thought we should finish university and get a real job first.”

When visiting manufacturers to investigate production, the trio was deliberately vague about their plans. “But by the time we got to the final factory, we just told them what we were looking to do,” she says. “The owner sat back in his chair and said, ‘Look, in my 15 years of manufacturing I’ve never heard of anything like this, but I want to get on board. I’ll do the first run of production for you and you can pay me back once you’ve sold the product.”

For Flynn, his decision was an early example of what the brand has been able to achieve. “I think what Thankyou has done is give consumers the opportunity to do something within their day-to-day lives that makes a difference.”

Sometimes it can feel as if small purchasing decisions are mere drops in the ocean when it comes to effecting real change. Certainly, we’d all be better off if people took larger steps such as reducing their overseas holidays and producing fewer children (I have four, so am failing there), but there’s truth in the notion that small acts can make a big difference.

Numerous studies show that millennials will pay more to buy sustainably produced products (although there’s sometimes a difference between what they say and what they do – price is still one of the two main major drivers of purchase, says Aziz). According to a Nielson survey last year, 81 per cent of respondents felt strongly that companies should help improve the environment, leading one commentator to state that “the phrase ‘not currently recyclable’ will become a barrier to purchase”.

As Aziz noted, part of this change is attributable to the imperative of climate change, but it’s helped by social media and what Ferrier describes as the “ultra transparency” of the internet. “We now have much greater access to the inner workings of corporations,” he says. “They used to be a black box and now they’re a glass box, so we find lots of them having to clean up their act.”

In a Nielson survey last year, 81 per cent of respondents felt strongly that companies should help improve the environment

To undertake this process properly is an “enormous, behemoth of a job”, says Marnie Goding, co-founder and creator director of Melbourne clothing and accessories brand ELK, particularly once you start drilling down into the detail of the supply chain. ELK recently produced a 122-page ‘Transparency Report’ detailing every aspect of the business, from the gender of employees to their work-life balance, where the company sources materials and its goals for full supply-chain traceability and zero waste by 2025.

“There are categories within the business that have always been sustainable, but when we started the business 15 years ago, this wasn’t something that was a topic,” says Goding. “But once you open that door to understanding the impact you have as an individual and a corporation, you can’t close it. And it’s the most wonderful process of discovery but also very frustrating and confronting to understand the [contribution of fashion] in the world regarding global warning and greenhouse emissions. We have a massive responsibility to make change – it’s not about being cool. It’s just that if I don’t do this, I won’t be able to sleep at night.”

For small to medium-sized companies like ELK, sourcing and verifying ethical manufacturers takes time. “We work 18 months to two years ahead,” she says. “So what I learnt yesterday you’re not going to see in market for another year and a half.” Adds Genevieve Smart, of Ginger & Smart: “The problem now is that a lot of people are presenting eco options but you really have to dig deep to find out if they really are.”

And with changing consumer expectations, brands can find themselves in situations they didn’t anticipate. Despite being a social enterprise, Thankyou has attracted criticism for selling bottled water when single-use plastic has recently become an issue. “The landscape is very different to when we started,” says Flynn. “I’ll be honest and say that as we’ve grown as a company we’ve got a lot slower than we used to be, and that’s something that’s quite disappointing for us. We probably should have pivoted a few years back with our water. It’s something that’s at the forefront of our focus and looking at making the water category more sustainable… and maybe there’s even a different way that we can provide water projects.”

While consumers are increasingly keen to shop ethically, Flynn emphasises the importance of having a good product for them to buy. “In the past there was a mindset that if it’s anything to do with charity, it’s ok for it to be average,” she says. “But my favourite quote on this comes from Martin Luther King Jnr – ‘all labour which exists to uplift humanity is important and should be undertaken with painstaking excellence.’ The people we serve deserve the best.”

Aziz puts it more bluntly: “You can’t have a shitty product. But when all other things are equal – the quality of the product and its price – the values of a company become important.”

In the future, perhaps, good won’t just be the new cool, but the new normal. “I think it’ll be standard,” says Flynn. “The expectation will be for businesses and organisations to be doing good.”

No Comments