There’s an enormous pair of gold-plated gorilla hands in the new Finkelstein gallery in Melbourne, and a pop-art-inspired piece by Louise Paramor that resembles an overturned green bucket. But these installations, while striking, aren’t the most remarkable feature of this basement space. Finkelstein is the only contemporary art gallery dedicated solely to female artists in Australia, and it is owner Lisa Fehily’s attempt to redress some of the issues that have hampered women’s careers for years.

“This is about helping female artists to become household names,” she says, as we wander through the echoing white-walled room. “I felt that there were so many incredibly talented women who needed assistance to push forward their career and get where they should be.”

As with pretty much every other industry, gender inequality persists in the art world – arguably more than most. Despite making up 74 per cent of art graduates, female artists feature in fewer commercial and public exhibitions than men. Only 34 per cent of the artists in state museum exhibitions are women. And female artists earn 25 per cent less than men – the average gender pay gap across all industries is 16 per cent.

“The world over, it’s the men whose prices are higher,” says Janet Laurence, one of Australia’s pre-eminent artists. “I’ve been told many times, even by my own dealer here, that women’s prices are always less.”

It’s the men whose prices are higher

But there are definitely signs of change. Fehily is one of several women who are leading a new push to help female artists achieve both the recognition and value that they deserve.

At the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, assistant director Alison Wright has spearheaded a campaign – #KnowMyName – to celebrate Australian female artists, while the gallery plans to host a major exhibition of women’s works starting in May next year.

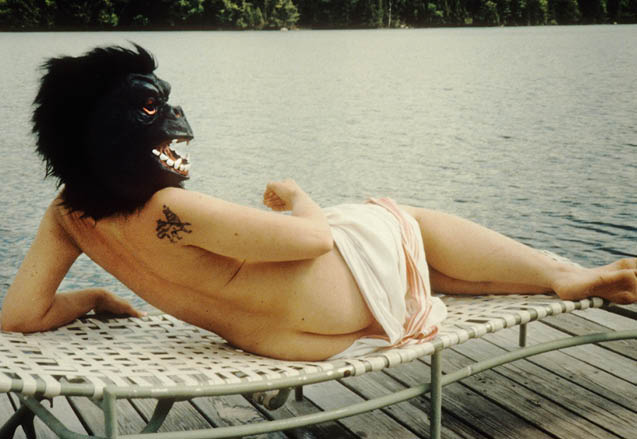

Meanwhile, the New Woman exhibition opens today at the Museum of Brisbane, featuring pieces from over 80 of the city’s most significant female artists. And this evening, Gerda Taro, one of the original Guerilla Girls – a collective of female activists and protesters famous for wearing gorilla masks to conceal their identities – headlines Talk Contemporary at Sydney Contemporary, the largest art fair in Australasia.

All of this attention on female artists isn’t happening in isolation; it’s part of an international movement to even the playing field. Most institutions globally have some work to do. Last year, The National Gallery in the UK made headlines after its purchase of a painting by 17th century artist Artemisia Gentileschi became just the 20th work by a woman in a collection of more than 2,300 European paintings. The NGA’s #KnowMyName was inspired by a similar initiative by the National Museum for Women in the Arts in the US which, in 2016, asked people if they could name five women artists (spoiler: hardly anyone could).

“It’s about time,” says Rachel Kent, chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, of the new push for female representation. “The big institutions across the world have been led by men, the staff have been male, the vision would have been male and the collections and exhibitions reflected that. I think it’s about looking at the institution, looking at the history and trying to do better.”

The history of women in art, of course, is pretty grim. We’re definitely represented in portraiture and sculpture – as reclining nudes or fashionable ladies sitting pretty in crinolines – but female artists are pitiably few. In the early 1990s, the Guerilla Girls campaigned with an incredible statistic that ‘fewer than five per cent of the artists in the Louvre’s Modern Art sections were women, but 85 per cent of the nudes were female’.

There are some big names like Gentileschi, of course, but not many others, for all the reasons you’d imagine – painting wasn’t an acceptable profession for women, they were excluded from schools and training, and when they did produce work it was rarely shown.

Many more women forged successful careers in the 20th century, but Janet Laurence still has some hair-raising tales of the “sexist and misogynistic” art scene when she was starting out in the ’60s. “I did realise it was very much this club of men,” she says. “At one stage, I had a relationship with a much older artist – one of these hero artists – and I was told by colleagues of his that I should let go of my own dreams and ambitions of being an artist, and just dedicate myself to his.”

Laurence, 72, has since exhibited her mixed-media art and installations all over the world, working across painting, sculpture, photography and video to create work that explores the natural world. Her ethereal 2018 installation, Theatre of Trees, for the MCA comprised huge concentric rings overlaid with translucent panels printed with images of the natural world. This solo show attracted 170,000 visitors.

“I did get the funniest review ever from a female art historian for my first solo show,” she adds. “It said: ‘Janet Laurence works with nature and the dark side of life, and this is not where a woman should be’.”

As a counterpoint to the ‘men’s club’ of the art world – and as a source of much-needed support – Laurence became good friends with other female artists such as Joan Brassil and Julie Rrap. “We used to form women’s groups of artists and we’d have wonderful meetings and share ideas about what we wanted to do,” she says.

In Brisbane, too, female artists from the 1940s onwards formed a close-knit arts community in response to the male-dominated field and the city’s geographical isolation.

“There’s a history here of artists not having a whole lot of support from government or galleries, which led to this ‘DIY’ approach, where women are working really closely together as each other’s teachers, influencing each other,” says Miranda Hine, curator of the New Woman exhibition. “If anyone went overseas, there was great excitement when they could share what they’d learnt.”

Some of the artists in Brisbane show, such as Margaret Olley and Margaret Cilento, were hugely celebrated during their lifetimes (Olley received a state funeral on her death in 2011), but most struggled to sell their work.

Newer institutions such as the MCA, where the entire senior curatorial team is female, have significant holdings of women artists’ work (almost 42 per cent of the MCA’s permanent collection is female), but the big state institutions don’t fare well. At the NGA in Canberra, women represent only 25 per cent of the Australian art collection.

We wouldn’t know many of these statistics if it weren’t for the work of Melbourne artist Elvis Richardson, whose Countess Report, released in 2016, was a landmark examination of the inequities still existing in the art world. “The closer an artist gets to money, prestige and power the more likely they are to be male,” it notes, wryly.

For Richardson, the report was “a way to present the facts without coming across as bitter or resentful, or being an angry woman. Just do it in a ‘report-y’ way and plonk it on the table, so to speak.” She sounds world-weary when talking about the treatment of female artists. “I look at my peers and all the men have had retrospectives, books, have been in biennales,” she says.

Perhaps the most well-known and respected art show in the world is the Venice Biennale, in which Australia has had a national pavilion since 1978. Although male and female artists are evenly represented, Richardson makes an interesting comparison on her site between the ages of the artists selected to exhibit. Almost three quarters (72 per cent) of the men were in their 30s or early 40s, where 66 per cent of the women were over 50.

“That’s on average a 15-year gap in age, and like the wage gap, 15 years is a measure of the extra weeks, months and years it takes for women to achieve the same milestones their male peers enjoy,” she writes.

The closer an artist gets to money, prestige and power the more likely they are to be male

If Janet Laurence were a man, would she have had a solo exhibition of the scale of the MCA’s earlier in her career? Yes, says Kent. “My guess is she probably would have. That’s not to say she hasn’t had some fabulous exhibitions before, but there’s a gap for women artists in this country. Janet is a really well-respected artist in this country and beyond. She is 72 this year – that’s a very long wait for a major retrospective.”

In the past, some critics have cavilled at the idea of all-women shows, arguing they ‘ghetto-ise’ women artists by placing them outside mainstream, male art. Laurence says she has “mixed feelings” about female-only exhibitions. “Maybe it’s necessary, but at the same time you see how good the women’s work is when they’re showing with men as well.”

But for other women, all-female shows are key to redressing the imbalance. Richardson says we need to “overwhelm” the barriers to women’s success by foregrounding women’s art. It’s important, too, she adds, that students are exposed to women’s work. While she was studying at art school, Hine says she didn’t hear about the female artists who played such a key role in developing her city’s unique cultural ecosystem. “Knowing them would have given me even more respect for what female artists in Brisbane are doing today,” she says.

Undoubtedly, progress is being made – several exhibitors in the New Woman show, including Tracey Moffatt and Jenny Watson, are some of Australia’s most internationally respected artists. Interestingly, Hine believes shows such as hers may not be needed in 10 years’ time as gender becomes less important, both as a site of inequality and as a binary construct. “It just might not be relevant as ideas of gender change.”

But for now, the fact remains that women artists aren’t as well known – and if they’re not being seen and valued now by curators and institutions, they’ll suffer the fate of those poorly-recognised female artists of the past. “Collecting is a process of writing history,” says Amy Prcevich, an artist who works with Richardson on the Countess Report. “With this new focus on women, we’re changing the zeitgeist and influencing how women will be remembered in the future, especially in larger institutions.”

Not all of us can buy art, but we can visit galleries and spread the word about female artists, adds Fehily. “Contemporary art is a mirror to our society,” she says. “It’s exciting, and it brings something to your life of value.”

Sydney Contemporary continues until September 15

New Woman is at the Museum of Brisbane until March 15, 2020

In November, internationally renowned UK artist Cordelia Parker is showing exclusively at the MCA for the Sydney International Art Series

No Comments