If you want to talk about Fifty Shades of Grey we’ve got to start with the numbers: 150 million. That’s the number of books sold in the trilogy. Fifty: How many languages it has been translated into (including Mongolian). $1.8 billion: The combined gross of the movie adaptations.

Even now, none of these numbers truly convey the wonder and the mystery of how a work that started life in the literary gutter, as Twilight fan fiction, became a cultural phenomenon, a zeitgeist-shifting chart-topper that was the fastest selling book in history.

Here’s another number: Ten. This year marks 10 years since EL James’ (real name Erika Mitchell) book made the jump from the murky corners of Internet fandom and was first released in e-book form by Australian publisher Amanda Hayward. (It was released in paperback in 2012.)

At the time the book came out – and as the hysteria and hype around the book ballooned – I sniffily refused to read it, clinging to some sort of illogical literary pretension. To be fair, criticism was widespread, with journalist Maureen Dowd opining that “James writes like a Brontë devoid of talent.”

But things change. Lockdowns happen. Mind-numbing boredom sets in.

But things change. Lockdowns happen. Mind-numbing boredom sets in.

Also, curiosity. Because the world has irrefutably moved on since 50 Shades was released. Today, ‘Popular with Women’ is one of the most viewed categories on Pornhub. You can now buy a vibrator when you stock up on sunscreen at Priceline. Forget putting out a fragrance: Stars including Gwyneth Paltrow, Lily Allen, Cara Delevingne and Dakota Johnson (who incidentally starred in the 50 Shades movies) have released their own sex toys.

What I wanted to know before diving in was, does 50 Shades still read as a provocative, taboo-busting page-turner? Or has it become a relic of a very different time?

In 2021, does Fifty Shades still matter?

First, a quick recap for anyone who hasn’t read the book. (It won’t take long; sophisticated literature, this is not.) The book opens with college student Anastasia Steele interviewing billionaire Christian Grey for a student newspaper. Grey is tantalised by the innocent and virginal Steele; Steele is beguiled by this reserved, inscrutable Adonis.

But it turns out that Grey doesn’t do vanilla sex, and instead presents the perpetually lip-biting Steele with a contract to become his sexual submissive. He wants to dominate her, not only in the bedroom, but outside it, too, and even prescribes what food Anastasia can eat and how she should maintain her pubic hair.

You know, boy meets girl, boy suggests girl spend three days a week in his Red Room of Pain. Classic stuff.

And yes, I know, I know, the writing is bad. Very bad.

Just to reiterate: “I’ve never read anything so badly written that got published. It made Twilight look like War and Peace,” Sir Salman Rushdie told the New York Festival audience.

To me, Fifty Shades reads like the human embodiment of a breathless Dolly Doctor letter. The phrases “Holy crap” and “Holy cow” appear 126 times. A perennially coy Steele seems wholly unable, even in her internal monologue, to use the word ‘vagina’ – and instead we are treated to, time and again, references to “there.” (“Desire pools way down low … way down there”; “He’s going to kiss me there!”; “Christian leisurely traces his fingertips down my cheek, and I feel it all the way down there.” Emphasis all James’.)

But I’ll admit this freely: I binge-read all three books in 48 hours.

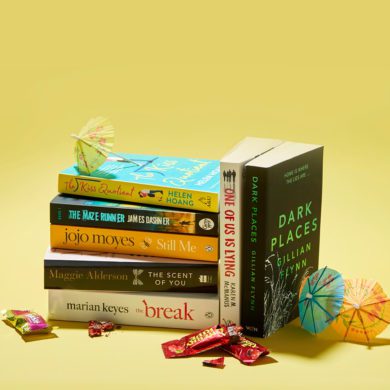

In part, it was a pleasure akin to scoffing a Milky Way under the doona; it was a joy to get lost in a ridiculous, preposterous confection of a world in true, soul-shaking love finds somehow finds a way, especially when real world is a bit miserable right now.

And in part, it was an exhausting and infuriating immersion into one couple’s toxic, troubled relationship with the occasional bit of, as the characters call it, “kinky fuckery” thrown in. Yes, I somehow find myself deeply invested in the duo’s romance (see above: Lockdown, incipient pathological boredom) but I found being submerged for hours on end in their maddening and troubling world a disquieting experience. I think one of the reasons I ploughed on, page after page, fight after fight, shower scene after shower scene, way I just couldn’t quite get a firm grip on whether Fifty Shades is simply entertaining pap or feminist atrocity.

I’m still not entirely sure. Maybe both.

Reading it, I was fascinated: How and why did a book that is surely the literary equivalent of a Big Mac indelibly change the cultural – and publishing – landscape?

How and why did a book that is surely the literary equivalent of a Big Mac indelibly change the cultural landscape?

Because love it or loathe it, Fifty Shades not so much shifted as jolted the zeitgeist.

Prior to its debut, much of this genre – women’s erotica – was hopelessly Mills & Boon-ified. Then 50 Shades came along and tapped into a hitherto hidden (or ignored) seam of female desire. Not only that, says Dr Hannah McCaan, a senior lecturer in cultural studies from the University of Melbourne, but Fifty Shades allowed women to explore “risky desires”.

“Some people, not just women, have all kinds of fantasies about being dominated with or without consent and rape fantasies. We don’t talk about that, and I think Fifty Shades really pushed the line there. It opened up this fictional space for exploring quite dangerous, problematic power dynamics that some people might find really sexy and like – and that’s okay too, because it is fantasy.”

Of course, other commentators saw erotica like Fifty Shades as rather less empowering. “If obscene wealth and sexual abuse is what gets you off, you go girl. Who am I to judge? But it’s not liberating,” says Linda Jaivin, essayist and author of erotic international bestseller Eat Me.

But reading Fifty Shades of Grey today, the biggest, 40-foot-high neon flashing problem is that, in the decade since the book was published, the conversation around control, dominance and submission has moved on. Significantly.

The conversation around control, dominance and submission has moved on. Significantly.

Reading Fifty Shades\] post-#MeToo, as debate swirls around issues like consent and coercive control, is a deeply troubling, confusing experience.

Is Steele’s ultimate acquiescence to Grey’s appetites a decision rooted in wanting to explore her own sexuality or is she being grossly used – or even abused – by a much more powerful, older man? Is she empowered by him to discover what really turns her on or does she submit to him because she is desperately trying to make their relationship work?

(There is also the much bigger question of: does it matter? It’s fiction, pure and simple. Do we have to apply the same standards to a novel that we do to real life?)

Is it romantic or queasy that a man who, in a matter of weeks, decides he wants to marry a girl who is 21 years old, secretly buys the company she works for, all while repeatedly taking control over her birth control? Who brusquely refers to taking her virginity by saying he wants to “rectify the situation”? Who quizzes her every time they meet about when she last ate?

Steele and the audience are meant to forgive his many, many transgressions and manipulative behaviour because of his disturbed past and the fact he does everything supposedly out of love.

(As Jaivin adroitly points out, “If Grey looked like Harvey Weinstein, or was dirt poor – or both – would all that he did still be okay?”)

The question of consent is very muddy at times. Grey repeatedly tells Steele she has the power when they are in his Red Room but at one point, he whips her, and she ends up sobbing and in real pain because she forgot she could “safe-word” out.

The question of consent is very muddy at times.

For McCann, one of the things that has shifted over the past decade is our thinking “about the grey areas of sex that aren’t necessarily rape or non-consensual, but are unpleasant and uncomfortable bad sex. Even if you’re consenting, “normal” can be a really bad experience.”

She argues the book’s real “cultural legacy” lies in the licence it gave female audiences to fantasise about “a kind of a grey consensual area” such as “non-consensual sex or to be dominated in a way.” Or to put it another way, it’s okay to get turned on by things that we find deeply abhorrent if they should ever stray from our imagination into real life.

Fifty Shades was a destabilising force when it was first launched, but there are sections of the book that have aged about as well as a cupboard full of Ed Hardy t-shirts.

(Not that this is unique to Fifty Shades. There are plenty of once-transgressive books that now feel out-of-touch. Lolita for one. American Psycho, with its torture scenes, for another.)

But there’s no denying that Fifty Shades shifted our thinking about women and sex. Would we be where we are now without James and her commitment to turning out screeds about there? Would Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop empire be selling a $750 gold-plated bondage set? Would Net-a-Porter be stocking a $1608 Saint Laurent cropped latex top which comes with its own special cleaning kit? Or Agent Provocateur peddling a variety of whips and paddles for discerning, BDSM-loving aesthetes?

But that power and potency is largely spent in today’s climate. If the book was published now, it would not land with a loud thud so much as get lost among the tens of thousands of similar titles on Amazon.

I dived into Fifty Shades with a weather eye on working out if it was still relevant. But in the end, the answer to that question came on the day of the photo shoot for this story.

I read Fifty Shades of Grey on my kindle, but PRIMER was keen to photograph me holding a copy of the book itself, so I rang bookstore after bookstore to try and track down a copy. Not a single one has a copy; many haven’t stocked it for over a year.

Even my most trashy-novel-loving friends have given their copies away or thrown them out.

We might be living in the world that EL James helped wrought but it seems we don’t want her on our bookshelves anymore.

1 Comment