You’ll have walked past women like Bec many times in the city centre, and barely given her a passing thought. After all, she looks like so many forty-something women, with her tailored black coat and shoes. Today she’s at a café, reading a newspaper, her dark hair pulled back in a messy pony. She’s an office worker on her lunchtime break, perhaps, or a mum enjoying a quiet coffee as life buzzes round her.

Except Bec is neither of those women. She’s here at the Salvation Army café on Melbourne’s Bourke Street to get a free meal in a safe, warm place and escape the confines of the hostel where she lives. “I hate it there,” she says quietly. “My room is so small and depressing. It feels like the walls are closing in on me.” She pauses for a moment. “But I suppose it’s better than being on the streets.”

For the past two weeks, stories about the difficulties of living on the government’s Newstart allowance (the main income support for people who are unemployed) have made headlines – ever since former deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce confessed to the economic strain of subsisting on his six-figure parliamentary salary.

Even as most of the country rolled its eyes, there was relief among workers in the sector that Newstart was at least on the political and media agenda. “I see young people on Newstart who can’t afford to live on it,” says Lee Turner, who works on the frontline of emergency relief services as team leader at Uniting Outreach Centre in Footscray. “Transport costs have gone up, [other] costs have risen, but no government has stepped in to increase payments.”

No government has stepped in to increase payments

And when those on Newstart have paid all of their immediate expenses like rent and bills, they often don’t have enough left over for food. Last year’s Hunger Report, produced by food distribution charity Foodbank, found that nearly one in five Australians experienced food insecurity at least once in the 12 months to April 2018 – and, shockingly, around three million Australians “eat less food than they need because they lack the money or other resources to obtain food.”

This is where charities and not-for-profits like the Salvation Army and Uniting come in, offering everything from food vouchers redeemable at supermarkets to food parcels and free meals. At Project 614, home to the cafe on Bourke Street, paid staff and a small army of volunteers serve breakfast to 150 people a day, and later provide a three-course lunch and dinner to a similar number. Over at Uniting in Footscray, Lee and her small team of six paid staff and several volunteers help over 10,000 people each year. And the demand for these services is only growing.

“People are finding it harder to make ends meet,” says Phoebe, 30, senior operations manager. “We’ve seen a huge increase in the number of people visiting our café since we opened three years ago. Lots of people spend the night here, where they feel safe, and then return to the streets in the morning.”

Project 614 is open for 21 and a half hours a day, every day of the year. We spent the morning here and then an afternoon at Uniting in Footscray, to learn more from the women who volunteer and those, like Bec, who rely on these vital services for food, company and the soul-nourishing feeling that someone cares.

9.30am, Thursday, at Project 614

On the third floor of this imposing Victorian building, a small team of women wait to welcome the first customers to the ‘marketplace’. This is where people can come to select fresh and tinned food if they’re struggling to find money to pay for groceries, along with hygiene products and other household items.

“They can come once a month,” says Sandra, a 73-year-old retired teacher who has volunteered here once a week for the last three years. “A single person can take 10 items, a couple 15 and a family 20.” They can take as many fresh vegetables and as much bread, donated by Aldi, as they want.

Everything is neatly presented on clean, white shelves, with tins of pantry staples like beans and chopped tomatoes on one side of the room and domestic products like washing detergent and soap on the other.

About 70 per cent of the marketplace’s customers are men; while I’m there, a tall, blond-haired young man with disabilities comes in to shop while his carer, Kinayo waits patiently for him in the small reception area outside. “I’m supporting him for the day,” she says. They’ll go shopping, and she’ll take him for coffee. “He’s a very gentle man,” she adds, smiling.

More women come in at Christmas, when they’re looking for some extra food to feed their children, and maybe to pick up some toys for presents. Some of those using the service have recently left abusive relationships, or they’re refugees whose bridging visas mean they can’t access the full range of benefits. Tonight, Phoebe is opening the marketplace at 8pm for a 40-year-old single woman who has struggled to find work since losing her well-paid job a couple of years ago. “She moved from Toorak, to Richmond, to Alphington to Salvation Army accommodation, and she feels guilty for using the service, because she’s not homeless,” Phoebe says. “I had to tell her, that’s not what the service is about. But it’s daunting for her.”

This is fulfilling work – both Phoebe and marketplace coordinator Marie, 25, love their jobs, but they admit their roles are demanding, with emergency calls for food relief coming through at all hours of the day and night. Marie took a call at 2am on New Year’s Day from police attending a house fire in Melton, in which a family with three small children lost everything they owned. “So we got up, collected some toys, clothes, food parcels and vouchers, and drove over,” she recalls.

Yet it isn’t this story, although sad, that makes her eyes fill with embarrassed tears, but the happiness she felt while dressing up as Mrs Claus for Christmas in July last month. “Walking into room full of people, all smiling at me,” she says. “I didn’t ever think you could make someone’s day with something as small as that.”

11am, in the kitchen

After the calm, organised quiet of the marketplace, the atmosphere in the kitchen on two levels below is one of bustling efficiency. Capsicum soup simmers in a huge aluminium pot on the stove and the air is heavy with the comforting smell of roast chicken cooking for lunch. For the last six and a half years, chef Adam, 38, has presided over this kitchen serving the café downstairs, helped by his part-time assistant, Alex.

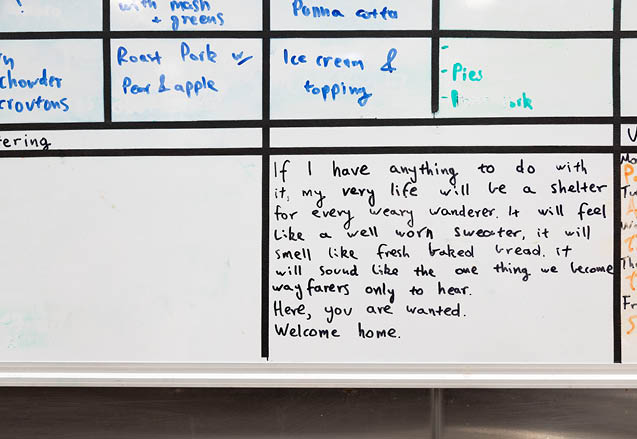

Standards here are high – with visible pride, Adam describes the process of straining milk through cornflakes to produce breakfast panna cotta with yoghurt and fresh berries. On the gleaming steel surface I count 10 enormous pieces of lamb ready to slow cook for tonight’s dinner. “Most of the food we use is donated from SecondBite and FareShare [which collect and redistribute surplus food], or from local restaurants,” he tells us as he goes from pot to oven. “Many people come here for three meals a day.”

Some of his customers are long-term homeless who’ve grown accustomed to sleeping rough, but others are desperate to get off the streets and into accommodation, says Phoebe. “The café isn’t a solution for homelessness, just a good option for people to be safe.”

11.30am, at the cafe

Sash, 51, sits in a pink striped jumper and pretty earrings to one side of the room, headphone blocking some of the music and chatter that rebounds off exposed brick walls and the fashionable concrete floor.

Like Bec, she doesn’t fit the stereotype of a women who might require food relief – she rents a flat in Footscray and is studying legal services, with fine art. “I’m an emerging artist,” she says with a sly grin. But Sash has suffered severe depression and a psychotic episode after losing several members of her family, which means she now lives on a disability pension of about $900 a fortnight. “I’ve tried to work, like selling essential oils and things, but people don’t have a lot of money,” she says. After paying $640 of her fortnightly allowance in rent, and then other bills, transport and study costs, there isn’t much left for food.

“I’m feeling isolated,” she says. “The only family I have are some cousins in the north of Victoria. So I come in here for a sense of community, as well as for food. Occasionally there’s a bit of shouting and it gets a bit rowdy, but the police can be here in five minutes.”

Phoebe tells me that increasing numbers of women are accessing their services, but many are reluctant to come here to the café to eat, as they can feel intimidated. There are about 30 people here now, enjoying their roast chicken lunch, and they’re mainly men rugged up in worn coats that have seen better days, one leaning his head on his hand as though burdened by the weight of his experiences. Some of these people have psychological ill health and their behaviour can be unpredictable. Women can feel vulnerable, particularly if they’ve experienced abuse.

At her table, on the other side of the room, Bec seems careful not to attract any attention. She describes her ex-partner as abusive, and says she is desperate to escape him. “He follows me from place to place, and he’s very volatile,” she says.

Bec has secured new accommodation in Melbourne’s west. She was supposed to move in on June 16, but what she describes as council issues means the date has been delayed and she is stuck in a hostel. Having moved around Australia and spent three months in prison for drug offences, Bec says she has few friends and no family down here. “The loneliness is difficult,” she says. “I haven’t touched drugs or alcohol for three years – prison was the worst three months of my life, bad enough to make me want to never touch drugs again.”

Until recently, she was studying for a Certificate IV in Alcohol and Other Drugs, in the hope she could become a counsellor to help other addicts to recover, but pressure from her partner caused her to place study on hold. “A couple of weeks ago, he stood over me and took my money,” she says. “I don’t have five cents to my name.” Usually, once she’s paid for hostel accommodation – about $340 a fortnight – she has $170 a week for everything else, which she says is just about enough to live on.

2pm, Uniting Outreach in Footscray

Team leader Lee Turner is precisely the kind of woman you’d want beside you in a crisis – which is useful in this inner-city suburb of Melbourne, which still has high levels of social deprivation. Her voice is low and calm, with a quiet authority that comes from years of working in social services, frequently with women and children experiencing family violence.

Here in Footscray, she runs an emergency centre that offers help to anyone who walks through the door. More often now, they’re women in their 50s and 60s, who are struggling to find work and feed themselves on the Newstart allowance, and younger men in their 20s and 30s. Lee gives them food vouchers to use at supermarkets, or parcels of food from the three rooms stacked with donated products. On Fridays, the room at the front of this red-brick Victorian building hosts a fresh-food market sourced from FoodBank. “We have 40 to 50 people queuing up outside,” she says. “It’s good food – we’re very careful to sort through and discard anything we wouldn’t eat ourselves.”

This afternoon, volunteers are busy packing food into bags ready for the market. Usually, eight to 10 people a day arrive for advice or help, but this afternoon there’s just one man who needs help to apply for a new health card, which he needs to access government services. It’s six months since he last came in, having lost the previous card, too. “You have to show a lot of sympathy,” says Lee. “If people are in pain, you don’t know what trauma they’ve had as children. You have to show kindness and respect.” She remembers the cries of one suicidal man exhausted by life. “People treat me like an animal’, he said.”

As a front-line worker, who refers clients to other services for accommodation and support, Lee knows all services are struggling. “To me, it’s getting worse,” she says. “Family violence is worse, lots of people are requesting support, and the cases are more complex, particularly with new drugs like ice. The anger on that is bad. People don’t see anything when they’re on it.”

But with the right support, people can turn their lives around. One hot, sticky summer’s day, a young guy – “quite tall,” she remembers – came in doubled over in pain. He refused an ambulance, but agreed to take a shower in one of the centre’s bathrooms. For 30 mins, Lee hovered near the door, worried he’d collapse. But afterwards, he seemed better, gratefully accepting a cup of weak coffee, a pair of socks and a food parcel. “He turned up at the counter a few months later and said to me, ‘You don’t recognise me, do you?’ And I didn’t. He was off drugs, and he said, ‘I’m with this lady now,’ the girl he had his arm round.” You always wonder about what happens to the clients you see, Lee says. “But hopefully he’s on his way now.”

No Comments