For more than a decade, Sarah* has worked for one of the big four Australian banks, starting in a full-time role before taking up a part-time middle-management job when she had kids.

Her loyalty and commitment has been rewarded with a recent job restructure, a workload she describes as “more than full time” and the news this week that her employer is paying its female staff more than 20 per cent less, on average, than its men.

“I felt shocked when I looked at the gender pay gap, but then also unsurprised,” says the Melbourne-based 40-something. Although the bank promotes its policies around gender and open communication, she adds, “there’s still an undercurrent that as a female part-timer, you have to be grateful for your job. And don’t rock the boat.”

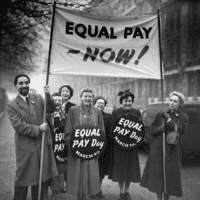

As women all over Australia consider the gender pay gap at their employer, that question of whether to rock the boat – with its potential for career upset – looms large.

Releasing gender pay data was never meant to place the burden of change on employees, says Mary Wooldridge, CEO of the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA), which was responsible for compiling the information, but it inevitably requires employee involvement.

I felt shocked when I looked at the gender pay gap

“We’re not putting the onus on employees – this is an employer-led opportunity for change and improvement,” she says. But “employees can very much contribute to helping the conversation in terms of priorities and experience.”

For women like Sarah, though, who wants to keep working for her employer (“it’s hard for me to walk away because I would very much like to be paid out for my many years of service”), the decision to speak up feels both risky and, potentially, futile.

“There are policies in place, such as equal parental leave and a whistleblowing team, but it seems that these initiatives help the employer rather than the employee. They signal all the right things, but I’m still not seeing any part-time women in senior management, for example. All these gender equality initiatives feel like gaslighting.”

And while there are legal protections for women who do choose to challenge their employer’s record on gender, few of us are perhaps willing to be branded a trouble-maker in an uncertain economic environment. It’s illegal to pay a woman less than a man for doing the same job, but “insidious and discrete forms of sex-based discrimination can be more complex and difficult to address,” says Penelope Parker, Senior Associate with Maurice Blackburn Lawyers.

They signal all the right things, but I’m still not seeing any part-time women in senior management

Overseas, however, the publication of gender pay data has led to a narrowing of the gap, at least in some companies. In the UK, which first published information from private companies in April 2018, the pay gap has stagnated at 9.4 per cent, but three quarters of organisations reported moves to identify the causes of their gap, including analysis of salaries, recruitment and promotion rates. Companies with worse gaps than their industry peers also showed a greater narrowing of their pay gaps in subsequent years.

“Publication of employer gender pay gaps in 2024 sets a comparison point for progress and it’s fair to say some employers are very focused on delivering a gender equal employer experience, but many aren’t,” says Wooldridge. “All have more work to do.”

So why publish now?

The WGEA hasn’t just started to collect this data: since the introduction of the Gender Equality Act in 2012, every employer with over 100 staff has been required to submit an annual breakdown of its gender composition and pay. WGEA then updated these employers on how their progress towards gender equity compared with similar companies.

The idea was that employers would use this data to address their gender pay difference – but progress was painfully slow. So last year parliament approved the publication of individual employers’ information. As we learned on Tuesday, the results were stark. Overall, the gender pay gap based on total remuneration is 21.7%, which means women earn 78c to the male dollar.

In fact, only one third of employers recorded a median pay gap in the target range of -5% and +5% (this allows for natural fluctuations in the employment of men and women in a company). Half of all employers have a gender pay gap of over 9.1% in favour of men.

Women earn 78c to the male dollar

There was an expectation that some of the more ‘traditionally male’ industries such as mining would post larger gaps (Glencore measured its gap at 41.4%). But it was a surprise to discover that several brands that sold primarily to women, such as Pandora (52.3%) and City Chic (57.4%), also posted a huge disparity.

Yet almost immediately, the data drew criticism. It was “useless data”, declared Nationals Senator Matt Canavan, arguing the WGEA report was an “Andrew Tate recruitment drive that just breeds resentment and division”. Many companies and commentators queried the usefulness of a median measure rather than a like-for-like comparison of similar roles; if 97% of your workforce is female and employed on the shop floor, while the majority of men are employed at the head office in IT or management, the median for men’s pay is going to be higher.

Companies such as Seafolly justified their median pay gap of 44.5% by explaining that 100% of its retail-based positions were filled by women, “with a significant number choosing part-time or casual work.

“Shopping for swimwear can be an intimate and personal experience, intertwined with confidence and self-expression,” it told Ragtrader, raising the question of how male customers feel when they’re served by one of the many female retail assistant in men’s stores. Perhaps their self-confidence is more robust?

“There’s always been a small number of naysayers in gender equality, but it’s clear there’s also a lot of support,” says Wooldridge, when asked about the backlash. “The gender pay gap is a proxy for inequality between women and men at work. Putting gender pay gaps of individual employers on the record is a catalyst for informed conversation and action that will accelerate change.”

Now for the hard part…

Knowledge is power, but the question of how employees can best use it remains vexed. From a legal perspective, it’s comforting to know there are significant protections in Australia for those who do want to raise the gender pay gap with their employer.

“While it may seem daunting to raise any pay disparity issue in your workplace, if you don’t it’s very unlikely that the issue will be rectified,” says Parker, of Maurice Blackburn Lawyers. “There are good protections for employees who raise these kinds of issues within the workplace. The general protections provisions of the Fair Work Act 2009 make it unlawful for an employer to victimise an employee because they have made a complaint or inquiry in relation to their employment. Complaints and inquires in relation to the disparity between men and women are likely to be covered by these provisions.”

There’s always been a small number of naysayers in gender equality

If you’re bullied or victimised as a result of raising the issue of pay disparity, you may also be protected under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984, Parker adds.

She recommends collaborating with colleagues in relation to gender pay gap issues (“there is power in numbers”). Previously, some employers added clauses to employment contracts that prevented an individual telling colleagues how much they earned. But since December 2022, there have there have been restrictions on doing that.

“Accordingly, employees who have entered into employment contracts after December 2022 cannot be subjected to disciplinary action for disclosing their salaries to their colleagues,” says Parker. “If employees are willing to disclose their salaries amongst their colleagues, there is less chance that any gender pay gap that currently exists will remain.”

It’s helpful, too, to know what other companies are doing. Superannuation fund HESTA, for example, has been conducting rigorous gender pay analysis since 2014. Its gender pay gap stands at 14.4% (not great, but far better than many other super funds) – a gap chief experience officer Lisa Samuels attributes to men’s continued dominance in its investment team, a traditionally ‘male’ sector.

“We’ve worked really hard to increase the number of women in senior roles in that team,” she says. Recruitment of women starts at a graduate level with three-month internships in the investment area, while HESTA also partners with an external provider for training and a returnship program.

If employees are willing to disclose their salaries amongst their colleagues, there is less chance that any gender pay gap that currently exists will remain

All leaders within the business know the gender pay gap in their specific area. “You can’t just hide under one number – you need to be clear about what’s driving it within the organisation,” says Samuels. “We also run stories internally about men taking parental leave, so we can normalise [the idea] that the challenges of managing unpaid and paid work don’t fall to one gender.”

We’ll really see change in the gender pay gap when men are taking parental leave and returning to work in part-time, customer service roles, says Jacqueline Graham, immediate past president of women’s networking organisation BPW (Business and Professional Women), which spearheaded Australia’s Gender Pay Alliance advocacy group. Societal expectations also contribute to inequity.

“There are more women in part-time, retail customer service roles because it suits their [caring responsibilities],” she says. “The corollary of this is to ask why there aren’t more men coming into those roles? How easy are we making it for men to play a more equal role?”

You can’t just hide under one number

At her bank, Sarah says she has asked executives directly whether there are opportunities for part-time employees to take senior roles – “and I’ve been told in black and white that it’s just not possible. I don’t see any role models ahead of me who are working anything other than full time. I don’t even apply for the more senior jobs now.”

“If you don’t have a partner who can also access flexibility – and can do so without feeling like they’re doing something special – the situation isn’t going to change.”

But companies that don’t respond positively to the gender pay gap risk more than just employee satisfaction, says the WGEA’s Mary Wooldridge. “I think they fail to act on gender equality at their peril,” she warns. “Recent insights from the UK show that there are prospective employees who are choosing to take a slightly lower paying job at an employer with a lower gender pay gap, presumably because it reflects the working environment and prospects for their career.

“This information can really shape the decisions of their future workforce, as well.”

*Details have been changed

No Comments