Over the years, I’ve discovered the best time to start a potentially ‘challenging’ discussion with my husband is when he’s feeling relaxed and happy, preferably with a G&T close to hand. So I waited until day five of our recent holiday to raise the thorny issue of household chores. It was late in the afternoon, the sun was casting its final rays on the turquoise ocean, and he was reading a novel on our balcony.

“So I’ve been thinking about how we run things now I’m back at work,” I ventured.

“Mmm-hmm.” He looked up and smiled encouragingly. His face wore a loving expression I could use to my advantage.

“I wondered if we could explore a few ways that we could rebalance some of the responsibilities at home,” I continued. This isn’t how I usually speak to him about chores, but I was using an opening line that psychologist Eve Rodsky suggested in her new book, Fair Play.

“Sounds good,” he said. “Let’s talk.”

“Oh, not now,” I said airily. “But definitely when we get back.”

Tempting as it was to seize the opportunity, Rodsky advises this first tete-a-tete regarding the contentious topic of housework should take less than five minutes. Laying the groundwork for success is key, she says. And having explored many other ways to recalibrate our home life, I was prepared to give her strategic approach a try.

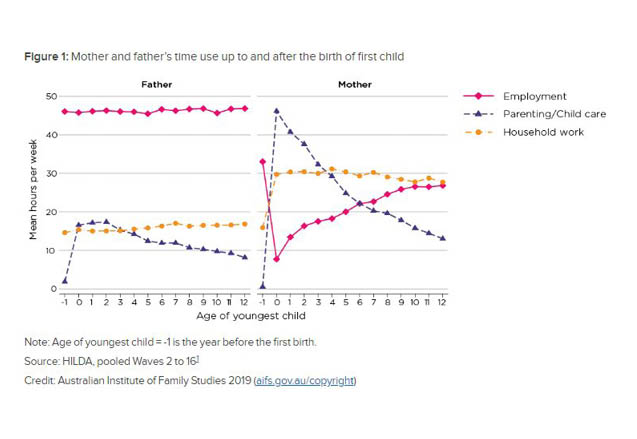

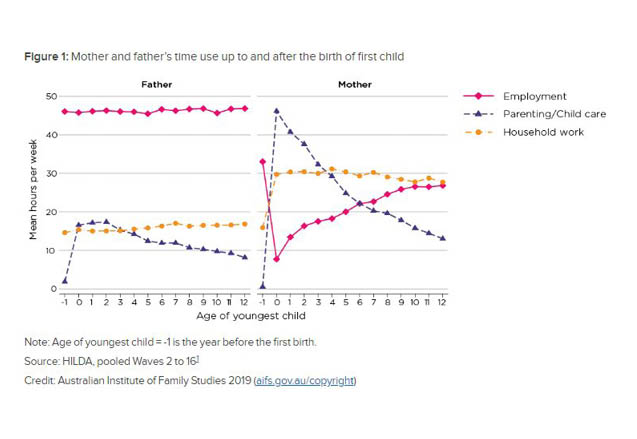

The fact that women perform most of the household chores in heterosexual relationships is nothing new. When women move in with a partner, they do more housework. On average, Australian women spend almost twice as much time as men on housework (almost three hours a day) and three times as much time on child care. Even if they’re the breadwinner, they still do more.

Certainly, this issue has been in the news recently, mostly thanks to Annabel Crabb’s Quarterly Essay, Men At Work, which looked at why so few men take parental leave or flexible working. Each of her appearances to promote the book last month sold out.

But while there’s been plenty of theoretical discussion about how to tackle domestic inequality – from paying women for their unpaid labour to forcing men to take parental leave – no one has yet devised a plan that sticks. Not on a societal level, not on an individual level. And certainly not in our house.

Enter Eve Rodsky and Fair Play.

Realising that simply identifying the problem wasn’t getting us anywhere, Rodsky decided to apply her impressive research skills – she’s a Harvard-educated lawyer and organisational specialist – to finding a practical solution. She consulted with psychiatrists and academics, and conducted 500 interviews with men and women in order to work out how to make our invisible work seen – and then devise the most efficient way of getting it done.

For me, Rodsky’s process was the first revelatory aspect of this book (and there are many): Simply by applying this rigorous and pragmatic approach, she elevates domestic work to the level of the other work we do.

Too often, discussions about the allocation of housework and the who-does-what of kids’ activities feel like petty concerns when there are so many other issues – like equal pay – demanding feminist attention.

But the fact is, women’s unpaid work has a huge effect on our ability to achieve economic parity. It’s also the kind of resentment-breeding issue that can fester like rotting vegetables at the back of the fridge.

Rodsky’s own revelation came when she received a text from her husband one day saying that a drunk guy had left a jacket and beer bottle in the middle of the front lawn of their LA home. At the time, she was on a one-day work trip to Seattle. “Weird. Gross. And more important, what am I supposed to do about it?” she thought.

When she returned home 16 hours later, the jacket and bottle were still there on the grass, in the dark. Waiting for her.

Seth, her husband, was stretched out on the bed, scrolling through his phone.

“While I’d spent the day working in another city, my husband also worked at his own job, but then had another four hours after the kids went down, during which he’d worked out, watched [TV], and checked Instagram,” she writes. “Plenty of time to decompress from his long day, and yet, somehow, not long enough to clean up the drunk guy’s stuff he’d discovered on our front lawn a full 16 hours earlier. His morning text wasn’t a ‘Can you believe this?’ text but the implication: I don’t have time. This is on you.”

As she snapped off the rubber gloves she’d used to pick up Drunk Guy’s mislaid items and deposit them in the bin, she realised this: “That Seth was not valuing my time equally to his.”

Rodsky’s argument is that men’s time is guarded as a finite resource (like diamonds) and women’s time is abundant (like sand). While the women’s movement has correctly identified that our time isn’t measured equally in the workplace (hence the pay gap), it has missed the message that our time isn’t fairly measured at home.

Rodsky’s argument is that men’s time is guarded as a finite resource (like diamonds) and women’s time is abundant (like sand)

I read this passage of her book on a plane home from a work trip, ironically, and it almost brought me to tears (possibly I was quite tired, too). This idea of the value of time really hit a nerve. When your partner is the main breadwinner, his time is more valuable financially, says Rodsky, but that doesn’t mean that other partner’s time has less value. “Time is a finite resource,’ she writes. “You are both diamonds.”

Viewed this way, we’re not discussing an allocation of chores, but an allocation of time.

In our house, an equal split of chores isn’t practicable, as my husband works longer hours with much less flexibility, but a fairer allocation of tasks is definitely possible. It demands, though, that we each take responsibility for the jobs that need to be done.

In Fair Play, this allocation takes the form of 100 Fair Play cards, which each represent a particular task. There are cards for groceries; meals (breakfast, school/lunch and dinner); cash & bills; social plans; auto… pretty much everything that a couple with kids needs to undertake in order to keep the household running relatively smoothly. The idea is that a couple divides up the cards and then takes sole responsibility for completing them. This means Conceiving, Planning and Executing each task, rather than starting an online food order while sitting on the sofa and yelling out, ‘Do we have honey in the cupboard? Do we need butter?’

The idea is that a couple divides up the cards and then takes sole responsibility for completing them

Most of the tasks I identified as mine – meals, laundry, plants, tidying – were the chores that needed doing almost daily; several of my husband’s jobs, such as health insurance and mortgage, were those that could be done at a time of his choosing. After I’d spent a few minutes wondering once again how I’d ended up in such a stereotypically gendered arrangement (and blaming the kids and… patriarchy), I remembered Rodsky’s observation that men’s tasks often fall into the ‘anytime’ category. Something to consider when thinking about assigning jobs.

Realistically, I knew that the chance of getting my husband to accept an actual hand of playing cards where the suits had been replaced with chores was, well, unlikely. Similarly, we would not be checking in each week to monitor our progress and swap some cards/chores, even though Rodsky strongly recommends it.

But we did, over the course of a few days, discuss where we might make changes to the way we operated. I realised that I needed to let him take full ownership of tasks involving the kids and to trust that he’s fine with that (I am a total micro-manager when it comes to the children, which I’ve realised I need to address). And I held close the idea that all time had value. If we worked more efficiently at home, we’d both have a lot more to enjoy.

Fair Play by Eve Rodsky, published by Hachette Australia, is out now

No Comments