Lying on the examination bed in her gynaecologist’s rooms in 2021, Jaime Criel had little reason to be nervous. She felt at ease with her gynaecologist, who had delivered her son just a year earlier, and she was hopeful that the intrauterine device (IUD) she was about to have inserted would relieve the heavy menstrual bleeding that had left her borderline anaemic.

Jaime didn’t give much thought whether the procedure would be painful. The 34-year-old make-up artist, who has tattoos trailing down both arms and has been inked more times than she can remember, knew she had a high pain threshold.

So, she was taken back by the “intense” pain of the insertion, and even more shocked by the fierce cramps that wracked her body afterwards as she returned to her car.

The pain was so severe that when she dropped her car keys, it took her a few moments before she was able to bend down and pick them up.

“It was the most amount of pain I’ve ever been in,” says Jaime now. “I was just so shaky. I couldn’t even move. It was just such an obscene amount of pain.”

It was the most amount of pain I’ve ever been in.

“I can deal with pain,” she repeats now. “But this was just such a different level. I remember thinking, does everyone feel like this? Why is no one talking about it?”

Increasingly, they are.

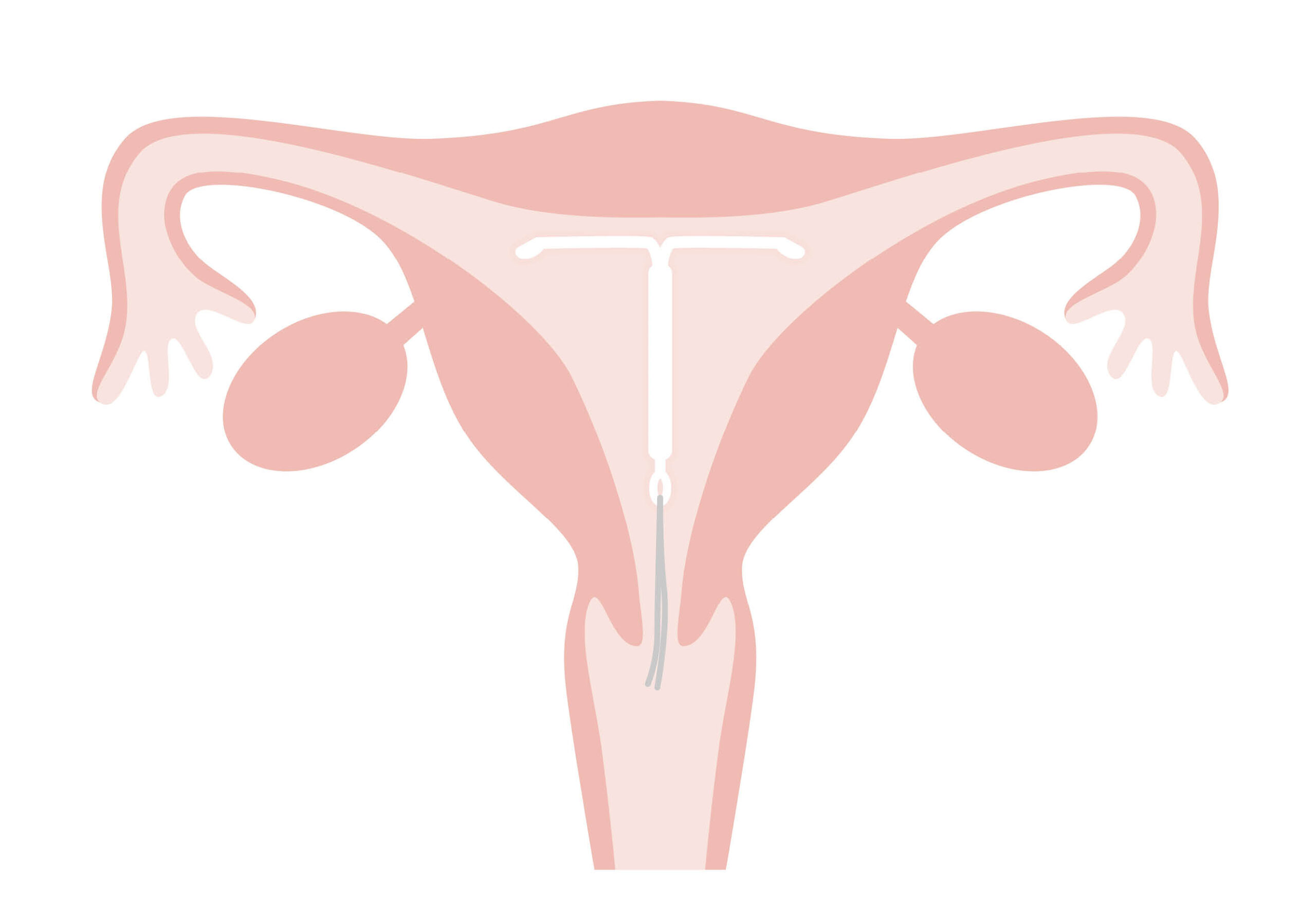

Across social media and on online forums, more and more women are swapping stories about the pain related to insertion of a hormonal IUD, which is a long-acting contraceptive device that is pushed through the cervix into the uterus and releases tiny amounts of the hormone progestin.

But, in doctors’ rooms and hospitals around the country, the message isn’t always getting through.

It’s unclear exactly how many women experience pain during IUD insertion – or why. One study found that nearly two-thirds of women found the procedure pain-free or only mildly painful and seven per cent considered it “severe”. Another study found that half of women who had never been pregnant felt severe pain.

But while many doctors are meticulous about letting female patients know that pain can vary, others are not. PRIMER has spoken to a number of midwives, nurses and medical students who have witnessed doctors minimising or failing to mention pain at all.

Access to pain relief options is even more inconsistent; although some clinics now offer the “green whistle” Penthrax inhaler (usually offered in emergency situations like ambulances) most don’t. Some provide anaesthetic spray or simply suggest that women take a couple of Panadol before the procedure.

Frightened by the horror stories they’ve seen on social media, many women are turning to expensive private health clinics where they can be sedated for the entire procedure, which costs between $450 and $700* depending on where you live. Others, unable to bear the cost or the pain, are abandoning the idea of having an IUD altogether.

That’s a shame says Professor Danielle Mazza, who is the chair of general practice at Monash University and an expert in women’s reproductive health.

A hormonal IUD is one of the most effective forms of contraception that we have.

“A hormonal IUD is one of the most effective forms of contraception that we have,” she says, pointing out that it is more than 99 per cent effective for five years.

“But it also manages heavy menstrual bleeding… and can be used to manage endometriosis. In menopause, many women use a hormonal IUD as one part of their hormone replacement therapy. So, it’s a product that can be used for multiple conditions.”

In Australia, the popularity of IUDs is rising… slowly. Last year, more than 160,000 prescriptions for Mirena or Kyleena IUDs were issued, according to the Department of Health, a 30 per cent increase over the past decade. But uptake in Australia is still low compared to other countries.

This comes as little surprise to women who have endured unexpectedly high levels of pain. Katie Dunn, 39, was warned by her doctor that she might suffer “mild cramping” after the procedure. But her experience went well beyond that.

“I couldn’t call it mild,” she says now. “I’ve undergone a lot of IVF treatments… I’ve also had spinal surgery. I’ve got quite a high pain tolerance.”

Dunn scheduled her appointment for the middle of her working day “so I could duck out of the office” but said the pain of the insertion was so intense she felt like fainting. “It really floored me. The nurse had to hold my pelvis down I was squirming so much.”

But it was later, while presenting a strategy at work, that she really struggled. “I had to focus really hard on the questions and use every ounce of my concentration because of the pain. I felt nauseous and dizzy.”

Looking back, she is frustrated by the lack of information. “Women aren’t told enough. I think they should be told what to expect.”

Katie and Jamie’s experiences are just two stories among dozens that were sent to PRIMER when we posted about IUDs on Instagram and asked readers for their feedback.

Many women were extremely positive about their IUDs and insertion; some described IUDs’ prevention of heavy menstrual bleeding as “life-changing”. Others described harrowing experiences.

“Horrendously painful,” was how one woman described it.

“Worse than at any point during my labour,” said another.

“I ended up on the toilet floor retching from the pain,” messaged another woman.

One experienced IUD inserter revealed told PRIMER that if she were to have an IUD, she would opt for sedation.

Another midwife said she had witnessed women sweating and passing out momentarily during the procedure. And yet doctors at the same clinic still described the pain as “just a pinching feeling” or told patients that pain relief wasn’t available (when the reality is that it just isn’t offered at their clinic).

I ended up on the toilet floor retching from the pain.

It’s testimonies like these that have helped convince doctors like Dr Nisha Khot that they need to take the pain around IUD insertion more seriously.

Dr Khot is the clinical director of obstetrics and gynaecology at Victoria’s Peninsula Health and says that the medical community’s approach to IUD insertion and pain needs updating.

“The vast majority of people who trained in obstetrics, gynaecology – in women’s health – were taught that putting an IUD wasn’t really painful procedure,” she says. “It could be uncomfortable, yes, but for the vast majority of women it would not be painful… just a scratch or cramping”.

It was only when Dr Khot came across an online forum where women were swapping stories about painful IUD insertions that she began to question what she’d been taught. “It was like a wake-up call. These were women who had experienced labour, and said that putting an IUD in was worse than labour pain.”

As a result, Peninsula Health recently began offering the “green whistle” inhaler, commonly used in ambulances, for IUD insertions. Dr Khot says around 25 per cent of women elect to have it.

“Some women take it up and say, ‘Yes, I want that.’ Others will say, ‘Look I don’t think I’ll need it. But it would be good to just hold it, just in case.’

It’s not clear why some women suffer pain during insertion and others don’t.

In her experience, Dr Khot says that women who haven’t delivered a baby vaginally (and therefore their cervix has never dilated), suffer from endometriosis or have a retroverted (backwards-facing) uterus are more likely to experience pain. Survivors of sexual assault can also struggle.

Despite these widely agreed risk factors, GPs are not issued with standardised guidelines advising them which patients may be more likely to require pain relief. Nor is there a clear pathway for referral; patients can be sent to another GP within the clinic for an insertion, a public hospital, a family planning clinic or a private health provider. All tend to offer different forms of pain relief and charge varying fees.

Many doctors say that it can be difficult to predict who will struggle with pain during the procedure. “You can have women who haven’t had children cope really well,” says Professor Kirsten Black, an academic gynaecologist at the University of Sydney. “And you have women who have who don’t.”

“Most people don’t have a bad experience,” she reaffirms. “I can put in an IUD really quickly. It’s about having the clinical experience to judge who is going to cope and not cope.”

Most people don’t have a bad experience. I can put in an IUD really quickly. It’s about having the clinical experience to judge who is going to cope and not cope.

Unfortunately, most GPs don’t have the necessary clinical experience. The procedure is not covered during undergraduate medical training, and most GPs don’t seek out extra training. This is partly because low Medicare rebates don’t cover the full cost of IUD insertions, which require special equipment and the presence of a nurse, while the courses themselves can be several thousand dollars.

“It’s not just the cost to do the course,” adds Professor Mazza. “It’s also that you need to take the week out of your diary so you’re losing income. Then for rural doctors, you’ve got travel costs, potentially childcare and accommodation. So, it’s not an incentive [to train].”

Even when doctors do register for training, waiting lists can be long. In Queensland, 200 doctors register to take part in an IUD insertion course every year, but the leading provider, True, only has 50-60 places. (This is because they must recruit up to eight patients for trainees to test their skills on.)

At True, doctors are encouraged to explain the risk of pain to patients. “When I’m counselling women prior to having [insertion] I always talk about the pain,” says Kelly Land from True. “That way, they can make a decision based on all the information.

“But when we’re infantilising women, when we’re dismissing pain outright and not giving them the full facts, that’s what I see as the problem.”

For Dr Jane Chalmers, a senior lecturer in pain at the University of South Australia, the prevailing attitudes towards IUD insertion and pain point to a classic case of “medical misogyny”.

“The medical community has been dominated by males for such a long time and women’s pain has been dismissed for such a long time that it’s just been ‘women complaining’.”

The medical community has been dominated by males for such a long time and women’s pain has been dismissed for such a long time that it’s just been ‘women complaining’.

She explains that women and men experience pain differently but that with no markers or objective measures for pain (“it’s a self-report thing”), it’s easy for medical professionals to brush women’s pain aside.

Thus far, there has been a woeful lack of attention paid to the issue by researchers. “Women are continually forgotten about and neglected. Even if I look at research into women’s pelvic pain versus men’s pelvic pain, there’s a gap there [in favour of research into men’s health.”

The same could be said for the research into women’s IUD insertions. The Department of Health does not track whether pain relief is delivered during insertions; nor does it measure the – anecdotally rising – rates of insertions under sedation.

Basic enquiries by PRIMER found that, in clinics that offer the green whistle, 15-30 per cent of women decide to use it, revealing that pain rates may be higher than some studies suggest.

At Clinic 66, a sexual health clinic on Sydney’s leafy North Shore, doctors perform 200 insertions under sedation every month. Director Dr Emma Boulton says that if the aim of contraception is to prevent pregnancies, then offering sedation is an obvious way to remove barriers to women getting IUDs.

She questions why women should be bearing any pain or cost at all. “It goes back to the question of who should be responsible [for contraception]. It takes two to tango, so why should a woman be the one taking the responsibility for contraception?”

It takes two to tango, so why should a woman be the one taking the responsibility for contraception?

One solution, she says, is for the government to cover the costs of sedation for any woman who wants it.

That may sound extreme, until you realise that in France, the government has covered the costs of IUD insertion for women under 25 for more than a decade. Last month, Canada announced free contraception, including IUDs, for all women.

Dr Nicole Higgins, the president of the Royal Australia College of General Practitioners, is keen to emphasise that most women don’t experience severe pain during IUD insertions.

But when they do, she says, “it’s not something we have to put up with because of our gender. We need to make sure that we make the experience as simple and as pain-free as possible.

“We need to address the assumption that because we are female, we should accept pain as part of the journey – and we definitely need more research to find out what works and what doesn’t.”

Three years on from her IUD insertion, Jaime Criel feels “fantastic” about her IUD. She no longer has periods or is borderline anaemic. “That part is amazing,” she says.

The key, according to both the women and the doctors we interviewed, is for women to be armed with as much knowledge as possible. “It’s really important to offer women a choice,” says Dr Sarah Callister, the medical lead for education at Family Planning Australia.

“Some women will say, straight up, there’s no way I’m doing [IUD insertion without pain relief]. But if you ask women to self-select whether they think this [procedure] is likely to be something they’ll feel ok about doing, most women will make a good judgement.”

“Women should have a good feeling about going in for an IUD insertion. They should feel comfortable about the information they’ve been given, and they should know what to expect. If they don’t have that feeling, they should perhaps keep looking until they find an organisation or person they do feel comfortable with.”

Want more stories like this? Sign up to PRIMER’s weekly newsletter

No Comments