I had only been a politician for a few weeks when I was approached in a Canberra bar and told, ‘The only thing anyone really wants to know about you, Kate, is how many blokes you had to fuck to get into parliament.’

This statement was made to me by a then Liberal staffer who went on to be a senior MP, who interrupted a conversation I was having at the pub during one of my first sitting weeks.

I had won a marginal seat from a popular, long-term incumbent Liberal MP in an election when my party was largely annihilated. But, sure, if that’s how he thinks elections work.

I had never spoken to him before and subsequently tried to limit our interactions over the next decade. It was the kind of run-of-the-mill sleaze and innuendo which is so common it is almost unremarkable in the culture of federal politics.

It was the kind of run-of-the-mill sleaze and innuendo which is so common it is almost unremarkable in the culture of federal politics.

I was interested to speak to other women about their experiences to try to determine exactly how often this was occurring in our parliament. Why does it happen? What impact does it have and is there a way we can prevent it?

In parliament, sexual rumours are often weaponised to destabilise a politician. When this happens, it is often the culmination of months or years of sexual gossip that has explicitly been circulated through parliament. It’s not exclusively aimed at women, but until the Four Corners report in 2020 very little had ever been reported or published about male parliamentarians’ sex lives. What is it that makes women the target of sexualised rumours? And why is it that some women cop it while others dodge it entirely?

I certainly copped my fair share in the 15 years I was in parliament. Perhaps I just exude an air of insatiable sexual animalism, but I suspect there is more at play.

Soon after my arrival in parliament, a rumour started that Labor Member for Watson Tony Burke and I were sleeping together. It was a rumour that would become widespread and persist on and off for most of the next decade.

Years later when my husband told one of his mates that we were dating his mate responded, ‘Is she still having sex with Tony Burke though?’ For what it’s worth, we never were.

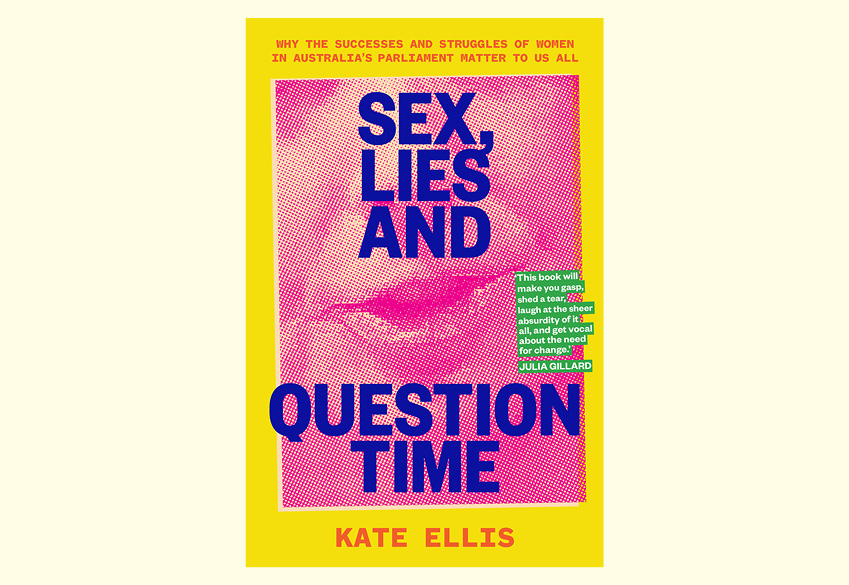

Rumours would follow about my alleged sexual liaisons with other MPs, ministers, countless staff members, sporting administrators when I was sports minister (the allegations seemed to peak in the years when I was a minister) and who knows who else. While interviewing women for my book Sex Lies and Question Time I learnt of rumours that had been spread about my sex life that I was completely unaware of until this point.

When I was heavily pregnant with my first child I hired a new and amazing press secretary, Joanne Cleary; she only recently told me that when she took the job she was warned by others that I was quite the ‘party girl’ and she’d need to work hard to keep my sex life out of the papers.

People apparently believed I was really, really busy. Not that it matters, or is actually any of your business, but I had two long-term monogamous relationships that lasted my entire parliamentary career. Beyond that, I wasn’t sleeping with half of Australia’s politicians or Australia’s political staff members or Australia’s men – in fact, none of them at all. But none of this is really about facts.

As Penny Wong noted, ‘Women’s sexuality has been used against us as a well-documented tool of control through much of human history.’

Liberal Cabinet Minister Karen Andrews mused, ‘I think women can be quite vulnerable to the shaming and rumours about who were they sleeping with. They can just be seen having a cup of coffee with someone and then all of a sudden, a rumour starts. That’s just nonsense. I think it’s immature but it happens and it is unacceptable.’

Sarah Hanson-Young entered the parliament as a married woman but became single after two years in the job. ‘There was a very quick change from the moment people discovered I wasn’t married anymore,’ she told me.

And it wasn’t long before she saw the result of this new interest in her personal life. ‘Bob Brown was still leader at the time … Bob is my political mentor. And he’s much older – I don’t know, sixty-something, close to seventy at this point. And he calls me into his office because someone upstairs in the Herald Sun, I think it was, was going to print a story about me being busted having sex in the prayer room.

‘They had gone to Bob for comment. And of course I’d never even put foot in that prayer room. I don’t even fucking know where it is.’

I don’t imagine many male backbenchers have experienced the joy of having to have these conversations with their boss. This specific claim wasn’t one that Sarah was unique in facing.

The Herald Sun, I think it was, was going to print a story about me being busted having sex in the prayer room.

Apparently I have also been known to use the prayer room for impromptu sexual liaisons. For the record, I, too, have never been to the prayer room. It does seem to be one of the first go-to rumours that gets spread about you though. Being caught having sex with a Comcar driver is another popular one.

Having your sex life – or rumours about your sex life – used against you serves a few different purposes. It can be used to try to put you off your game in the parliament, it can be used to undermine your credibility among your colleagues, or it can just be gossip for people’s entertainment.

Labor MP for Kingston Amanda Rishworth told me, ‘I think that it is something that is used as a weapon. I had one experience where it was yelled across the House of Representatives chamber, “We all know that you effed such and such”.

It was deliberately done to make me feel uncomfortable and to undermine me in front of my colleagues.’ Sarah Hanson-Young agreed. ‘Yeah, I think it’s designed to play with your head.

The motivation for the attacks on me was different. The rumours weren’t always sexual in nature, but almost always undermined my worth. In politics, people often ‘background’ you, which means they speak to journalists and spread rumours but do so ‘off the record’ so that it is never traced back to them.

The rumours weren’t always sexual in nature, but almost always undermined my worth.

One of my colleagues backgrounded the media that I was known as ‘The Pot Plant’. The suggestion was that I looked nice but didn’t add any value.

When Tanya Plibersek and I were discussing some of the various rumours that had been spread about us, she brought a new one to my attention. ‘You had that whole vajazzling thing to deal with.’

I had no idea what she was talking about. Absolutely none.

She went on to explain that there had been a little piece in one of the papers about how one female minister had taken preparations for the annual Midwinter Ball so seriously that she had been seen earlier that day checking in to a local beauty clinic to be vajazzled.

For the uninitiated – and the unvajazzled – the practice of vajazzling apparently involves having pretty gemstones and sparkly rhinestones adorned to your pubic mound, to jazz yourself up downstairs.

‘The whole parliament was talking about how it was you!’ Tanya informed me.

Um, no, that would be drastically overstating my commitment to personal grooming.

‘The whole parliament was talking about how it was you!’

It’s tempting to see this sexual weaponisation as just another manifestation of inter-party politics: the same-old Liberal versus Labor but with a sexual twist. That’s part of the story, but it’s not the whole picture. If it were, surely we’d hear a lot more about men’s dodgy sexual encounters.

The reality is that there are also plenty of examples of the weaponisation coming from inside your own party.

I was just 30 years old when Kevin Rudd appointed me as the Minister for Youth and Sport and I became Australia’s youngest ever federal minister.

We had just had a huge win in the 2007 election. We had a backbench brimming with talented and ambitious caucus members. Many would have seen themselves as much more suitable and deserving potential ministers than me. Of course, in politics, you can’t be promoted until there is a position open and available. You can wait it out, or you can try to hurry things along.

Proving that I was frivolous, unprofessional, stupid or lacking commitment would go a long way towards delivering a vacancy in the ministry for those who felt more deserving of it. Outlandish sexual rumours would be a great way to start.

Like many industries, networking and building personal relationships play a vital role in getting ahead in politics, and the power of the boys’ club is in what happens away from the workplace. But being seen out and about also hugely increases the amount of gossip spread about you.

Like many industries, networking and building personal relationships play a vital role in getting ahead in politics. But being seen out and about also hugely increases the amount of gossip spread about you.

Sarah Hanson-Young talked about how the rumours about her started. She believed that the most ridiculous was that she was sleeping with journalist Tony Wright, who she said was ‘old enough to be my grandfather’.

It was a rumour I had myself heard many times, in the parliament, in media circles and back in South Australia. ‘It came from being seen at Aussies [a cafe in Parliament House] having coffee or at the pub having a beer when we were talking about asylum-seeker stuff. He’d been to Manus Island and Nauru before and I hadn’t been there. Just being seen, a young female politician talking to an older man in the gallery, people thought, oh, they must be fucking.’

Sarah Hanson-Young explained the professional consequences of feeling that, as a woman, you weren’t free to go out for a drink with other politicians and journalists. ‘It cut us out of that conversation and that ability to have influence. Like that’s where the real conversations happen. They don’t happen in the chamber and mostly don’t even happen in people’s offices. You work out who’s talking to who and about what, if there’s any alliances on issues.’

Eventually Sarah decided that being exposed to rumours was a risk she had to take in order to be part of those conversations. But many women raised with me their lack of socialising and networking in comparison to their male colleagues. The potential to be implicated in sexualised rumours if seen out and about adds to the existing power imbalance. It means that women are left with an impossible choice: do we vacate the sites of information sharing and network building or do we face the reputational consequences of playing the same game as men? Or can we find a third way?

Another issue facing female MPs is how they socialise and deal with the media. For a variety of reasons, female MPs reported having much less inclination to seek out journalists and those with influence without a specific and compelling reason to do so.

Julia Gillard noted the ease with which men managed to glide into this parliamentary environment which for women remained confronting. ‘Looking back on it now, I realise that a lot of the young men coming into parliament just felt a breezy, easy confidence to take up more space in the world.’

She recounted frequently running into male MPs who had been to see the CEOs of major Australian brands just to introduce themselves. ‘It always used to rock me back on my heels, like, why would the CEO of a business as big as that make time to see an incoming MP? And what sort of a degree of confidence would you need to have to think that they would reorganise their diary to see you?’

Boys’ clubs are far from exclusive to the parliament. Women in many industries still note the informal work and networking done by their colleagues on the golf course, at the pub or in a strip club. I do think this is improving in the broader business community.

In politics, however, the exclusive nature of the boys’ club is increased due to the possibility that if a woman does venture out into networking territory, she opens herself up to a new range of slurs.

And it is certainly not always men spreading this gossip. Former federal Labor MP Emma Husar has her views on this. ‘What I’ve learnt about slut shaming is that it actually starts with women and then men weaponise it. Women talk about it. Gossip about it. Then it’s the men who actually weaponise it in an employment setting and use it to prevent women from getting promotions, women from climbing any further than where the men get. Keeping them constrained.’

For the most part, the sexual gossip stays in the shadows as persistent and undermining rumours. It may seem pretty harmless at times, it may be annoying at others but it can also be something much larger – significant and life-altering lies. Weaponising sexual gossip can be much more dangerous than just rumours. It can end women’s careers.

This is an edited extract from Kate Ellis’ book Sex, Lies And Question Time (Hardie Grant), which is available now.

Want more stories like this? Sign up to PRIMER’s weekly newsletter

No Comments