I am dying. I know that I am dying, despite not having been told by my doctors that I am. I know I am dying because I’m in the dying room. It’s quiet and people slip in and out as if they were never here.

For what seems like the longest time, I’ve been a body in a hospital bed – a bundle of atrophied muscle and chalky bones, the timbre of my breath thick and craggy. I feel the yawn marching in my winter lungs and hear the final infection coming, slow at first then roaring like a diesel engine into my living corpse, filling it with blood and pus and mucus. I can taste my death in the internal suppurations I cough up, the smell like rotting oysters.

It’s an odd thing, being able to taste your own death. For years, X-rays have shown the infection blooming across my chest like a stain, but I’ve never tasted it, or felt the pain so acutely. If you’ve ever had a baby elephant trample your ribcage as you struggled to breathe underwater through an occluded straw – this is what it feels like to die. There’s no talk of palliative care because people like me aren’t palliated: we don’t have time – death comes across upon us suddenly.

For what seems like the longest time, I’ve been a body in a hospital bed

I decide it’s easier to die, simply because it’s impossible to go on. It will be painful, yes, but easy. But there’s one thing I want to do before I slip into the inevitable coma, and that’s to see my friends one last time. To say goodbye, but mostly to say: I love you; thank you for loving me.

I’m ready to die, but the world wants me to stay. So, I do. Like an unarticulated vow, I stay.

***

It’s just before midnight, and I’m sleeping upright in my hospital bed. I can’t lay flat because my lungs are swimming in infection. I get a sense of how it must feel to drown slowly. The shrillness of the phone slices through the smell of decay that’s been hanging like an invisible curtain in my room for weeks.

I presume it’s my boyfriend, Ollie, calling to see if he can come up and sleep in my bed, although he usually just materialises in my doorway, drunk and happy.

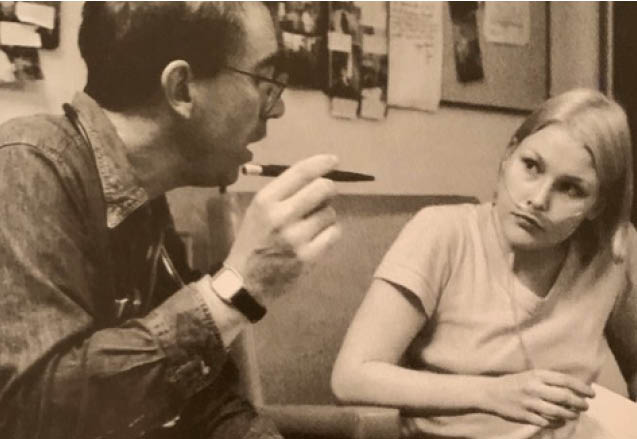

But it’s not Ollie. It’s my cystic fibrosis (CF) doctor, Simon, and because I’m levitating on a billowing plume of morphine, I think how lovely it is that despite the hour, he’s calling for a leisurely chat.

‘Hey, Simon, how are you?’

I can sense him smiling through the phone. ‘I’ve got great news, mate. We’ve got a set of lungs for you.’

‘Oh my god. Really?’

‘Really.’

‘Holy fuck.’

‘Ha! That’s exactly what your sister said.’

My thoughts move to my sister, Nikki, as I imagine her at home, tripping over in the darkness as she reaches for the phone.

My mind whirrs as Simon explains that I’m going to be transferred by ambulance from the Mater Hospital to the Prince Charles. When I hang up, a couple of the nurses gather in my doorway, tears spilling down their cheeks. My night nurse, Daisy, who has seen me fade from a firecracker of a girl, helps me pour my child-sized body into a pair of jeans and wrangle on my blue Chuck Taylors.

I call Ollie. He’s not long home from a night out with the boys. He sobers up in record time. ‘Oh my god,’ he says slowly. ‘I’ll be there, babe. At the hospital. And for you. Holy shit. I love you.’

Next I call my best friend, Laura.

‘Holy fuck! This is amazing. I’m leaving right now. FUCK!’

I leave her in charge of calling my friends before she bolts out of her house and runs a red light on the way to the hospital. Dad runs two.

I’m wheeled downstairs to the emergency department; outside, the ambulance sits in its bay like a hearse waiting to transport the living dead. During the night, squalls of rain have moved down into the city from the ranges. As we drive over glistening ribbons of road, a solar eclipse stretches its way across the Earth. A jolt of flavour lands unexpectedly on my tongue. Initially, I think it’s humidity, but I know rain doesn’t taste metallic. There’s blood in my mouth from coughing, and I wonder if it’s the last thing I’ll ever taste.

When I arrive at The Prince Charles Hospital, Mum, Dad and Nikki are waiting for me, as is Ollie. In an act of drunken devotion, he has bought flowers and a box of chocolates from a service station, even though I have to fast before surgery. We’re taken up to the ward, and more friends arrive.

During the night, my transplant physician, Scott, joins us, holding handfuls of paperwork. He looks flustered but excited.

‘It’s not going to be easy,’ he tells me.

‘I know.’

‘But it’ll be worth it.’

‘I hope so.’

‘It will be. It’s just not going to be easy.’

At 7:30am, I’m taken downstairs to the operating suites. I’ve been nothing but calm the entire morning and remain so as I hugged my parents and sister goodbye and give Ollie a final kiss. As I’m wheeled into the operating theatre I’m sitting up on the gurney, but when I glance back, I see everyone there and I begin to howl. I’m howling because I’m certain that I’m going to die on that table, and I’ll never see my loved ones again.

This is my clarion call.

***

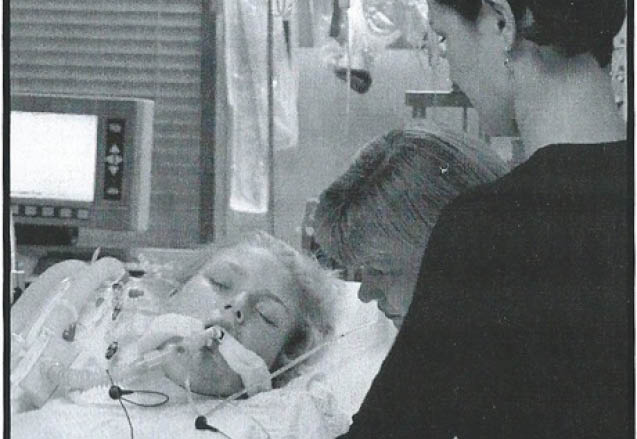

DAY 1

When I am intubated and my sedation is lowered to wake me up, I point out my first words on an alphabet board.

‘Am I alive?’

Everyone giggles and says yes.

Then I spell out, ‘I love you’ before I am sedated again.

DAY 4

On day four, I am awake and breathing on my own – in part. In part, because I’m breathing with another person’s lungs. Where I should feel elated, I’m in such a stupor of pain that I want to know how the nurses let a lunatic into intensive care to pour fuel over my chest and drop a lit match.

It isn’t just my chest burning – it is as if my soul is aflame. But when I look down, all I see are four hoses poking out just beneath my breasts. Later, I will allegorise this searing pain as the husk of my old body falling away; like a slipping of skins and the exquisite agony of being caught between being a girl and a woman.

TWO WEEKS LATER

Exactly a fortnight post-transplant I have two blood transfusions, after which I begin throwing up. Scott is concerned, but because my X-ray looks ok and my chest doesn’t sound too crackly, he’s happy to wait and see. He tells us that night that I have three things on my side – great family support, good nutrition, and a brilliant set of donor lungs. In his words, ‘the best set he has ever seen’.

I’m on huge doses of steroids and I begin taking a newer anti-rejection medication. I might look like a chipmunk from the steroids, but according to Mum, I’ve had enough and am ‘over it’. I just want to get better.

Scott’s words would prove to be somewhat prophetic. This was not going to be easy. Nothing about this was easy. After three weeks in hospital, I go home to begin my new life.

AFTERWARDS

In the aftermath of the surgery, I was in a constant state of vigilance. If there was someone coughing or sneezing near me, instead of seeing a human all I saw was a germ factory. Toddlers with snotty noses? Harbourers of disease and death. The first time I went out to dinner, someone was smoking at a nearby table, and I had a panic attack.

It took a couple of years for my hyper-vigilance to abate. I was more frightened of living than dying.

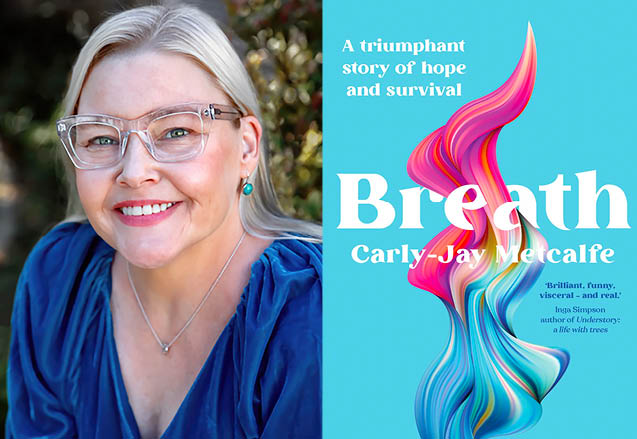

Yet, I also felt a great sense of urgency because I knew I was on borrowed time. Back then, in the late 1990s, morbidity rates were high even after a transplant, and my family and I hoped I would have maybe five years. Anything after that was a bonus. Then I made it to a decade; soon it was 15, 20 years – every day felt like a permutation of a gift and something of a fever dream.

I was more frightened of living than dying

My recovery was nothing like those I’d heard about, where people woke up and breathed unencumbered, and without pain. That was not my experience. I may have had a new, upcycled body, but my mind was a grease trap, and bringing myself to a point of stillness – to a place of peace – proved impossible. I felt out of step with time; that there had been this radical intrusion to my body. I never mentioned this to anyone because I felt it would come off as sounding reckless and selfish.

When you have a transplant people are under the impression, and have the expectation, that you will feel like a new person. Instead, I had to lie and tell people I felt great, instead of, ‘I still can’t breathe, everything is fucked.’ Along with thrice-weekly clinic appointments, infusions, and blood tests, there was the task of working out who I was. After a lifetime of illness, who was this new woman I had become? I didn’t know her, and as such I didn’t know how to be in the world. The clinic appointments grew further apart, but the existential angst seemed infinite and something I could not reconcile.

SURVIVOR’S GUILT

From the moment I woke up after surgery, there seemed to be a million things to focus on, but the most pervasive thought was that of my donor and their family. Whoever they were, they were now a part of me, braided into my body, blood and cells. While it made no logical sense, I felt a degree of complicity in their death. Then, there was the labyrinth of guilt into which I’d descend when another CF friend died. I never felt like I deserved to be here, to be alive.

Survivor’s guilt would be something I would grapple with for the rest of my life – both for my donor and my friends who did not survive.

In the end, my doctor Scott was right about everything. He was right about transplant not being easy, but he was also right when he said that it would be worth it, because I survived when so many of my friends did not. I feel extraordinarily lucky that I’m still alive.

I’ve come away with far more than I have given, and far more than I have lost. I have come away with my life.

No Comments