On Mother’s Day earlier this month, Rachael Casella got up early and baked her mum pancakes just the way she likes them – drenched in maple syrup, bacon and berries – before they exchanged presents.

It was a special morning in many ways – her parents had driven up from Canberra, just a few days after the interstate border had reopened post-lockdown. But it was still achingly far from the Mother’s Day that Rachael, 36, had once imagined.

Two and a half years ago, Rachael’s chubby-cheeked and blue-eyed seven-month-old daughter Mackenzie passed away from complications related to spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a terminal, congenital condition. As though this weren’t tragic enough, Rachael has since undergone nine gruelling rounds of IVF and fallen pregnant twice more – only to discover that these babies, too, were afflicted by SMA.

Since then, each Mother’s Day, birthday and holiday, Rachael has unable to resist reimagining an alternate reality: a world where all her children are alive. “Mackenzie would have been three now,” says Rachael, a warm and composed police investigator. “She would have snuggled me on the couch, and then we’d go to a playground.

“I know exactly how she would have looked because I always wanted to give her a little fringe and put her hair in a top knot. She would have looked beautiful.”

Her eyes start to redden. “It’s ok,” she says, brushing away concern. “I love talking about my daughter – just like every other mother.”

Rachael has spoken often about Mackenzie in the past two years as part of a determined fight for wider access to genetic carrier testing, which would have revealed that she and her husband, Johnny, had a high risk of giving birth to babies with SMA. In turn, this would have allowed them to improve their chances of having a healthy child by conceiving via IVF.

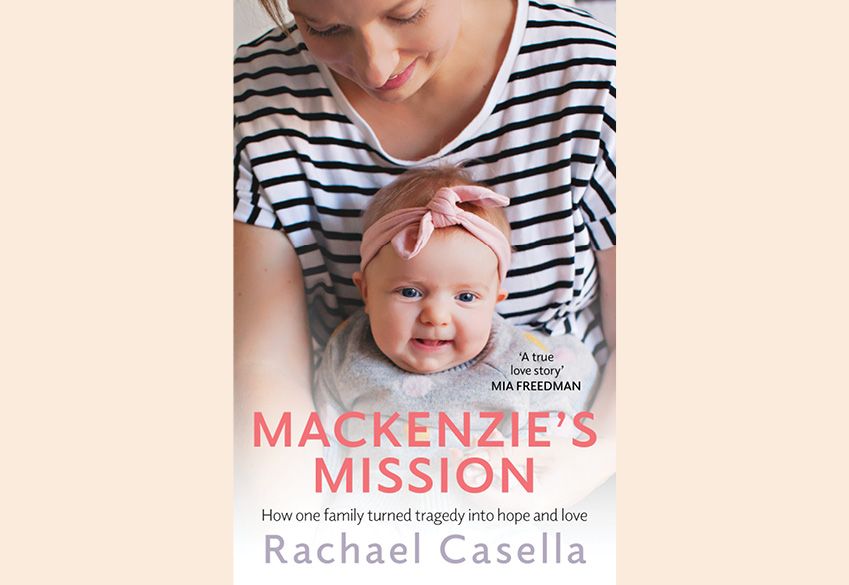

This week, Rachael’s campaign will culminate in the launch of a $20m government-funded pilot called Mackenzie’s Mission. If everything goes to plan, all Australian couples will soon have the opportunity to be tested for 1700 genetic conditions – potentially sparing them the grief that the Casellas have endured. This week, too, sees the launch of Rachael’s book, Mackenzie’s Mission, about her daughter’s short life and Rachael’s subsequent struggle to conceive.

“Sometimes I’ve felt a little bit like I’m a one-woman band,” says Rachael of her three-year battle. “But everything I do – the whole purpose of this book and everything I do on Instagram and on my blog – is because people need to know about genetic testing.”

When Rachael and Johnny fell pregnant with Mackenzie, they knew very little about genetic testing and nothing at all about SMA.

They first met at work in 2013; Rachael was training as a police officer and Johnny was one of the senior instructors. Three years later they were married, and three months after that they fell pregnant. “We were over the moon,” recalls Rachael in Mackenzie’s Mission.

But the couple’s joy was short-lived. At six weeks, Rachael miscarried. Devastated, they named their unborn baby Hope, and began trying for another child.

Within weeks they were pregnant, and this time it went smoothly. Mackenzie was born on March 11, 2017 and over the next 10 weeks Rachael and Johnny settled into the joyful, if sleepless, rhythms familiar to most new parents.

Mackenzie, a beautiful baby with huge eyes, was only nine weeks old when Rachael noticed something odd: with worrying regularity, Mackenzie had started to cry at the end of every feed. So, Rachael took her to see a lactation consultant, who advised her that although there was nothing wrong with Mackenzie’s feeding, she had concerns that the baby seemed “floppy”.

The diagnosis of SMA, made by a gruff paediatrician a few weeks later, was devastating. “I felt my whole body shut down,” Rachael recalls. “Everything went blurry, sounds were muffled, and I felt like I would collapse.”

The Casallas scrambled to learn everything they could about the terminal condition, which is a form of motor neurone disease and gradually strips sufferers of the ability to move, swallow and, eventually, breathe. It is the number-one genetic killer of babies under two in Australia, and children who are born with Type 1 SMA, like Mackenzie, have an average life expectancy of just eight months.

The news got worse. To their horror, the Casellas discovered that SMA only occurs when both parents carry a specific gene – and that a simple blood or saliva test before conception would have revealed that both Rachael and Johnny were carriers.

Looking back, Rachael says that the couple took every screening test offered to them during pregnancy (including the non-invasive prenatal test or ‘NIPT’ also known as the ‘harmony test’), but that the possibility of a genetic carrier test was not mentioned. Had they known about it they would have opted for one, and then turned to IVF to pre-screen for healthy embryos – sparing them the agony of witnessing Mackenzie’s gradual decline.

Instead, after the diagnosis, Rachael and Johnny became dedicated to the twin imperatives of making their daughter’s final months as joyful and memorable as possible, while simultaneously lobbying the government to ensure that other couples would never face the dizzying shock and grief they were experiencing.

Over the next five months, the Casellas spent time with extended family to create memories with their baby daughter; they tried to introduce her to as many tastes as possible and they travelled to Perth and Broome on holiday; they even took her to the snow, witnessing the magical moment that little Mackenzie, whose limbs and reflexes were already beginning to fail, stuck out her tongue to catch a falling snowflake.

But one morning in early October while the family was at home, seven-month-old Mackenzie began to turn pale blue. Rachael frantically rang an ambulance and they were raced to hospital.

Doctors realised that Mackenzie had caught a cold, but because of SMA, she was unable to fight it off and her body was deteriorating rapidly. For four torturously long days and nights, doctors tried to save her.

Eventually Mackenzie slipped into unconsciousness, and it became clear she would not recover. “We had told staff early on that we would not keep making her fight at the cost of her quality of life,” recalls Rachael in her book. “We wanted her to feel no pain.”

We told staff that we wouldn’t keep making her fight at the cost of her quality of life

The family was moved to a big double room to say their farewells. After cuddling and talking to Mackenzie and reading her favourite books aloud, Mackenzie’s breathing tubes and oxygen mask were gently removed and she passed away, lying between Rachael and Johnny.

In her book, Rachael recalls the devastating aftermath. “For an age, we just held her and cuddled her, breathing in her scent and touching her hair. Eventually we undressed and bathed her, and dressed her in her own clothes and swaddled her in a hospital blanket. They told us someone would take her down to the morgue, but I refused. No one would carry her to the morgue but me.”

Today, Mackenzie remains a poignant presence in the Casella’s Eastern Suburbs apartment. A photo of her, alongside her dummy and the bunny she was holding when she died, sit on Rachael’s bedside table. They are the first things she sees when she wakes up, and the last things she sees at night. Down the hall, Mackenzie’s nursery remains preserved in time; her cot stands ready, as though she might return at any moment, and her nappies are still stacked in piles. Mackenzie’s car seat and pram remain in the couple’s car.

“We’re not sad people,” insists Rachael. “We look at Mackenzie as a gift. When it first happened, I just burst into tears. Now, when we think about her, we smile. Johnny sings songs to her. We’re not a sad house. We’re a very loving house.”

We’re not sad people. We look at Mackenzie as a gift

After Mackenzie’s death, and despite their grief, the couple embarked upon IVF. They have since undergone nine rounds, and have fallen pregnant twice – once naturally, with a baby they named Bella, who was found to have SMA, and once via IVF, with baby Leo, who was discovered to have a severe chromosome condition.

Unable to face the prospect of proceeding with a pregnancy, only for their baby to die mere months later, Rachael and Johnny opted for a medical termination in both instances.

“We’ve just become the unluckiest couple. Our fertility specialists and the head embryologist said he’s never seen anything like it before. I thought well, our daughter died, surely we’re not going to have to fight any more to have children.”

Throughout the endless, rolling disappointments, the Casellas have clung tightly to a few vital comforts: their marriage; the loving support of their family; a virtual cheer squad in the form of Rachael’s growing social media community – and the progress they have made in campaigning for wider access to genetic carrier screening.

Today, Rachael is determined to ensure all couples who are pregnant or trying for a baby are told about genetic carrier screening. Although the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recently changed their guidelines, and now recommend that all couples undertake genetic carrier screening (rather than just those with a family history), many pregnant women are still unaware that genetic carrier screening exists.

“It will take a while before this is commonplace. But even the NIPT was barely done five or 10 years ago and now it’s common.”

In 2018, as a direct result of the Casellas’ campaigning, the government also announced funding for Mackenzies Mission, and, so far, 70 couples have taken part in a pilot programme. If the pilot succeeds and a nationwide screening programme is rolled out it will become the most comprehensive of its kind in the world.

Rachael has been contacted by a dozen couples who have taken part in the study. “I’ve been contacted by people who had positive results, and were found to be carriers, saying thank you. I’ve been contacted by people who weren’t high risk, which meant they could get on with getting pregnant without the stress. I honestly believe that the tests will change people’s lives.”

As for the Casellas and their long journey to parenthood? When we speak over Zoom, Rachael has just undergone a series of obstetric procedures and is due to find out within days whether the latest embryos are SMA-free. “Maybe I’m delusional,” Rachael says with a wan smile. “But I feel like maybe this will be it.”

You can follow Rachael at My Life Of Love on Instagram. Her book, Mackenzie’s Mission, is available from June 2 or to pre-order here.

To find out more about genetic carrier testing, visit Mackenzie’s Mission or speak to your GP.

No Comments