Like every other fashion designer, Natalija Bouropoulus was affected by lockdown – and by April, sales of her delicate silk and linen pieces had completely dried up. “It was really stressful,” says the Sydney-based designer, 34. “I had this collection of pieces ready-made and I couldn’t pay my makers because I didn’t have any cash coming in to the business.”

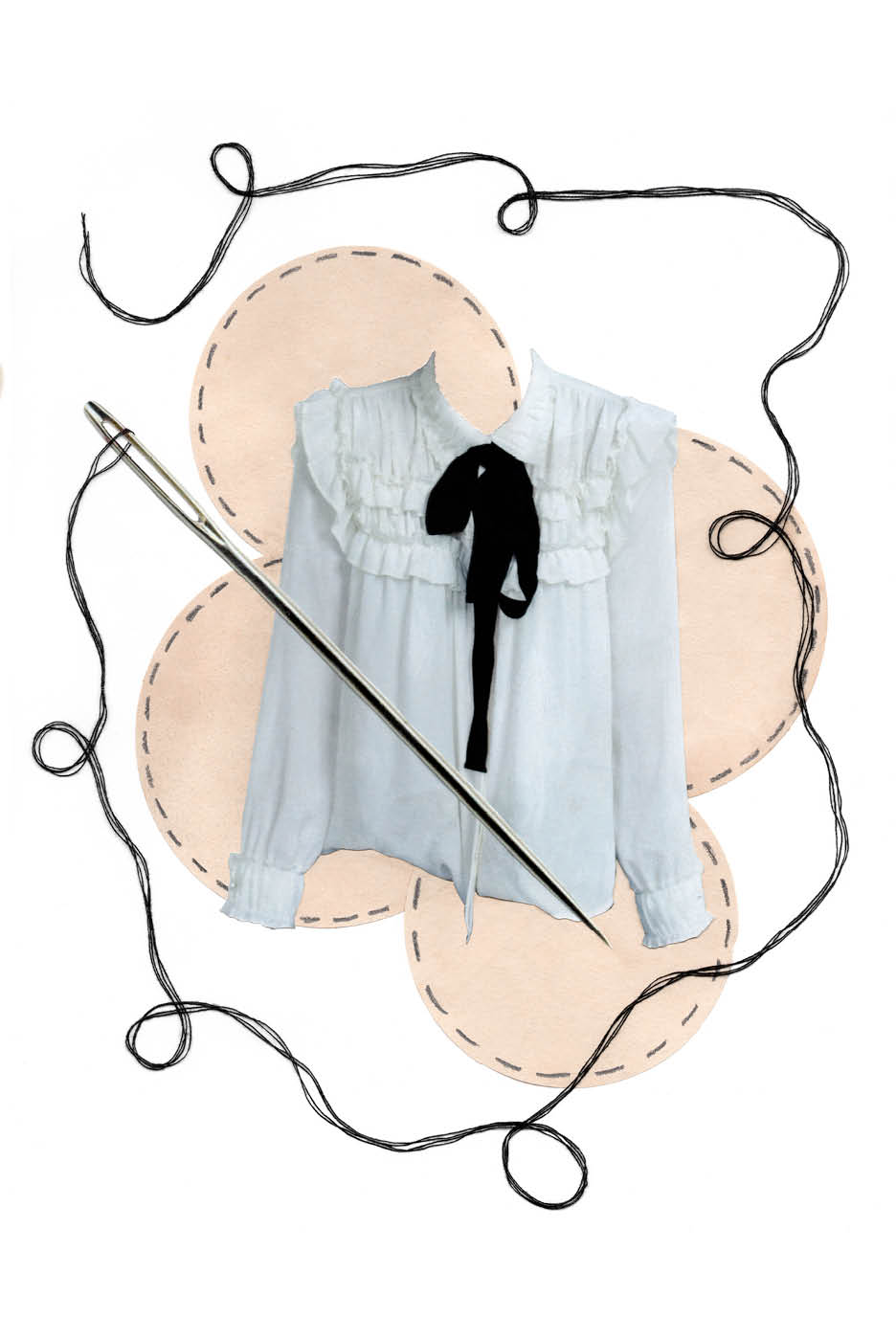

So Natalija made a decision she’d been considering for a while: she pivoted her label, Natalija, to a made-to-order model, where a dress or camisole, for example, would only go into production once a customer had ordered and paid for it. This proved to be a smart move – not only could she alter garments to suit clients’ different body shapes, but selling direct to consumer also enabled her to take control of her inventory.

“Now we have money sitting in the business, and we’re not carrying any debt,” she says. “I’ve also found returns have reduced, as women are purchasing intentionally, rather than just buying a slip dress on the fly.”

Natalija’s pivot to made-to-order places her among the new wave of designers who are pioneering a shift away from mass production towards a more considered way of shopping. Overseas, Insta-famous brands like Olivia Rose and Maison Cleo were among the first to normalise made-to-order online, while here brands like Citizen Wolf, Natalija, Kalaurie and D’Arce cover a spectrum of apparel from t-shirts to dresses and delicate sandals.

Customers benefit from a better fit and, in many cases, the chance to choose from a greater range of fabric and colour. But it’s the environmental advantages that are game-changing.

“The fashion industry is really unsustainable,” says Natalija. “We’re creating more garments than we need. So, yes, it’s scary to close all your wholesale orders and step away from everything you know, but we can’t keep going the way we have.”

Today, most of us are aware of the environmental costs of society’s fast-fashion addiction, but the statistics are worth repeating: Every year, the average Australian buys 27 kilos of clothing and throws away 23 kilos – making us the second-largest consumers of textiles in the world (after the US). That means six tons of clothing goes into landfill ever 10 minutes.

Globally, more than eight per cent of global greenhouse-gas emissions are produced by the clothing and footwear industries.

Fast fashion always gets the blame for all this – and deservedly so. In 2018, Swedish retailer H&M reported that it was sitting on $US4.3 billion ($AUD5.9 billion) of unsold stock.

But it’s not just H&M; the way that most retailers operate is environmentally challenging, argues sustainability expert Suzana Tas, founder of Responsible Fashion Agency in Sydney.

The fashion industry is really unsustainable

“Retailers order ‘buffer units’ to ensure they don’t run out of stock, but it means they’re always left with excess inventory, which they have to get rid of.” They can discount it heavily or – as Burberry admitted to doing – destroy it to protect the perceived value of their brand.

“Making so many garments so far in advance, and then crossing your fingers that they sell is a fundamentally broken system,” agrees ethical manufacturer Zoltan Csaki. “The planet desperately needs a better system.”

Four years ago, Zoltan and his business partner Eric Phu founded Citizen Wolf, a made-to-order t-shirt brand that uses a ‘Magic Fit’ algorithm to customise fit.

The initial concept came from Eric’s complaint that he couldn’t find a t-shirt that wasn’t too long – and the fact he could get anything he wanted tailored to fit in HongKong, where he was then living.

“But although we started off trying to solve his fit problem, we quickly understood that what we really wanted to do was fundamentally re-think and re-engineer the way clothes are made at scale,” says Zoltan. “We want to prove that made-on-demand is a viable alternative to mass production. We’re using made-to-order t-shirts as the Trojan horse.”

Where Natalija uses a network of seamstresses from a family-run business to produce her silk pieces (“I’ve found some great seamstresses that have been sewing for leading Australian designers for 40 years plus”), Zoltan and Eric established their own factory. While Zoltan admits that running a factory adds complication, the advantage is the ability to scale – something that other made-to-order brands would struggle to achieve quickly. “We can basically triple output by running a 24-hour operation,” he says.

However, there’s no getting round the fact when you buy made-to-order pieces, you can’t have them straight away – you have to wait. Citizen Wolf t-shirts take about a week from order to delivery (the lovely olive-green one we ordered, in the spirit of journalistic integrity, was delayed by a few days because the fabric was stuck in Melbourne); Natalija’s pieces take a couple of weeks.

Both designers regard this process of ordering and waiting as a positive aspect of the business. “What we’ve discovered is that the relationship with clothes that you have made for you is fundamentally different to the relationship you might otherwise have,” says Zoltan, who encourages customers to look after their t-shirts by offering lifetime repairs. Natalija includes a card with each garment that tells the customer the name of the seamstress who made it: “It’s a beautiful way of establishing a personal connection.”

The model also reduces the amount of fabric waste and enables labels to know every stage of their supply chain. “We need to trace every fabric back to its beginnings to ensure it’s sustainable,” says Natalija. “Our linen is deadstock from fashion companies that have over-estimated their needs, so we keep our supply chains quite short.”

The relationship with clothes that you have made for you is fundamentally different

It’s hard to imagine this approach to fashion will ever fully replace the traditional retail model – that’s difficult when you can pick up a t-shirt for $10. (Citizen Wolf t-shirts start at $69 and Natalija silk slips are $298.) “The younger generation is pushing back against mass production, but the entire structure of how we produce needs a shake-up,” says Suzana.

Meanwhile, Zoltan is pinning his hopes on a technologically-led move towards mass made-to-order. “Sew bots already exist but they’re expensive right now,” he says. “Like every other technology, they’ll become cheaper in time.”

For Citizen Wolf, he adds, T-shirts are just the beginning. “We’ve always said that t-shirts are just the proof of concept for a fundamentally better way of making clothes.”

Want more stories like this? Sign up to PRIMER’s weekly newsletter.

No Comments