I stand looking up at the towering wall of bandaids in the chemist. There are too many to choose from and I am finding it confusing. My confusion must be evident as one of the women who works there approaches.

‘Can I help you find something?’

‘Um, yeah, I need wound dressings.’

I continue looking along the shelves as I speak. ‘My dad has had a heap of skin cancers removed and the stitches are pretty extensive, but also my Dad is a unit, he’s real big like 6 foot 5 and—’

‘Amy, I know who your dad is.’ The woman smiles as she interrupts. I stop looking at the bandaids and focus on the shop assistant.

Seeing her properly this time – she does look kind of familiar. I consider where I am: this is Dad’s local chemist. He comes here regularly for his methadone program.

He’s been coming here for decades now – so of course they know Dad – and by extension that means they’ve known and know me.

I relax, glad for the help. Together we gather the larger dressings and some saline. She gives me instructions on how to apply the dressing before reminding me only Dad can collect his methadone script, so I will need to bring him in for that. I thank her, dash across the car park and drive to Dad’s.

Dad comes here regularly for his methadone program

He isn’t working at the moment – can’t work – and now with the surgeries on his leg he can’t really do much of anything until he’s healed up. After cleaning and dressing his leg, I make us coffee while he calls his own dad to remind him I will be on the television tonight.

As well as being an academic at a university, I am a semi-regular on a news panel show; tonight they’ve flagged with me that the topic is incarceration. So I want to talk with Dad a bit about it before I go home to prepare. We eat biscuits together and talk about the violence of lock-up, the work of doing my thesis, how the kids are going in school, and the idea of a family trip to the zoo in the upcoming school holidays. We haven’t been to the zoo as a family since I was a kid.

******

The crinkle of the thin plastic tray of chocolate biscuits makes me smile and hold my breath as I slide it out from its purple wrapper. As quietly as I can, I take a chocolate biscuit finger out, listening for Mum in the bathroom but there is only silence. I grin and hold the biscuit before sliding the tray back into its sleeve, and tiptoe over to the twin beds in the musty motel room we are staying in.

My baby siblings are too young to be aware of what I am doing as I sit behind them on the floor. Max is a newborn, and Taylah isn’t quite two; they are watching the motel TV. I lean up against the foot of one of the beds and feel very proud of myself for this little act of defiance.

This week, Mum and Dad have booked a cheap motel and we are going to the zoo tomorrow. I am hoping to see a white tiger; they are my favourite and I borrowed a book from the school library to learn as much about them as possible. I am eight years old.

The bathroom door swings open and I drop my shirt sleeve over my hand to cover the biscuit that I’ve started eating. I stop chewing. It is a game: concealing from Mum that I snuck one of the biscuits she told me to leave ’til after dinner. She doesn’t look at me, instead walking between us children sitting on the floor, and going around the bed that I lean against.

I feel feel proud of myself for this act of defiance

At first, I think she is waiting to hear me crunch the biscuit so she can spring upon me. I am very still and the chocolate is melting in my mouth in a such a way that soon I’ll be able to swallow without detection. I am a genius.

But then I realise that I am not the only one who is suspiciously still. I feel it first in my belly – a gnawing and growing sense of panic that spreads under my skin to my fingers and toes and the top of my crown. I can feel her lack of movement. Where is the breath that should be on the back of my neck, the chuckle I was waiting to hear as she caught me with the biscuit? Her signs of life are missing.

I want desperately to turn my head to look at her. I want to scream for help. I want my dad to be back from running an errand. But I am paralysed. Time passes. Silence. If it weren’t for Tay’s coos and chattering, and the animations that dance across the grainy television screen in front of me, I would have thought that time itself had stopped.

But only Mum’s breathing has.

I have no idea how much time passes – this will be a problem later. I know better than to go for help but I also do not know what to do in the meantime. So I do nothing but hold myself as perfectly still as my little body will allow.

Finally, Dad walks in and out of my mouth tumble the words, ‘Mum is asleep.’ He looks at me – my tone has alerted him. He sees, he knows, he swings into action. ‘How long has she been asleep for, Amy?’

I stand up. ‘I don’t know.’

He steps over to her and lifts her light body in his arms in one swooping motion. As he drops her onto the single bed against the wall, I see him pick something up from within the bundle that her body has become; it is bright orange and he moves it into his pocket. In the black and white haze of the terror I feel – the orange burns into my brain. It is the cap off a syringe.

Mum’s body is now on the bed and Dad tells me to run to reception and ask them to call an ambulance. He says it calmly, firmly, but I won’t move. I am standing, crying – I cannot move. He isn’t looking at me, he is looking at her but he knows I haven’t moved. He begins to yell at me as he compresses on her chest: one, two, three.

‘Amy! Go!’

I see him pick something up from within the bundle that her body has become

But I still don’t move. She is dying; I know it, and I am terrified. He stops to bend and breathe into her. Again, one, two, three. He presses on her chest with such force that her arms flail up and down. Her arms are flapping wildly and she looks like a rag doll – lifeless under his compressions. I am transfixed.

He yells at me once more. One, two, three: ‘AMY, AMBULANCE, GO, NOW!’

With every compression she looks simultaneously like she may well break under his force but also like a bird trying to take flight. So much movement but her body is also limp as he breathes into her mouth and continues compressions. Her face is empty and grey.

Dad is panicking. He turns his head and looks at me, spit flying as he screams, ‘AMY, GO, NOW! TELL THEM WE NEED AN AMBULANCE!’

I am eight. I don’t dare defy him any longer. I move, open the motel room door and dash across the car park. I burst through the glass door of reception and shout at the receptionist whose face I cannot see through my tears. ‘Please, we need an ambulance. My mum is dying, hurry!’

They nod and grab the telephone and as soon as I am sure they understand, I am sprinting across the car park again. I burst back into the motel room but everything has changed. Gone is the chaos of Dad compressing Mum’s chest; instead, everything is still. Mum’s eyes are open. She breathes. She is alive. What comes next feels worse than all that came before.

‘Amy, go and tell them we don’t need the ambulance,’ Dad instructs me.

‘No!’ I may only be eight but in that moment I am defiant once more.

‘Amy, go back and tell them it was a mistake – we don’t need the ambulance anymore.’

I look at my mother: she is still grey. She was dying, I won’t do it.

‘AMY, GO!’

I go.

Across the car park once more, slowly this time, into the glass and red-brick room. The receptionist is shocked. I am just a child but they listen, and again pick up the phone. I am disappointed that they listen to me and now the ambulance won’t come. Every single cell within my being is screaming at me that we need an ambulance but I do as I am told.

Again, I walk back into the motel room. I wipe my streaming nose on my sleeve and my melty chocolate hand down my shirt. Mum is no longer in the main room. She is in the shower.

Very quickly the tiny motel bathroom fills with hot steam; it is suffocating. Mum sits under the hot jets and I rest on the sink. She wants to know what I saw, what I know. How will I tell this story when we are again around family? is what she means.

I am desperate to follow the rules, and in this family, the rules change a lot. So I keep details to myself; I do not mention the orange cap, or the fact I know she died. I keep the fact that I feel overwhelmed by the shock and terror of watching and feeling her life disappear right beside me, sensing her shift from walking in front of me, to dying on the floor right behind me. Instead, I tell her anything I think she wants to hear; I just want out of this bathroom.

Later that day Mum and Dad teach me how to check if someone is breathing – the sounds, the sights – and impress upon me that I am responsible for being aware of the movement of a person’s chest. I feel responsible for everything that has happened that day.

With a combination of intense love and deep fear, for the next few years I will develop the habit of waking in the middle of most nights, panicked that their breathing will have stopped. I will creep into my parent’s bedroom and listen as long as it takes for me to distinguish there are two sets of lungs moving in the darkness before I return to my bed.

The next day, we go to the zoo. As we leave, they let me pick a white tiger toy from the souvenir store. It is just a hard plastic toy, but that’s not how I see it. The layer of faux fur is soft and I think it is perfect – it has pretty blue eyes that I stare into for the whole drive home.

I keep the secret of the orange cap and what happened in that musty motel room. A few weeks later I take the tiger toy into the bath with me. The hot water seeps in between the plastic and the faux fur, lifting it, disintegrating the glue in seconds until I am left holding nothing but the hard plastic, lifeless mould.

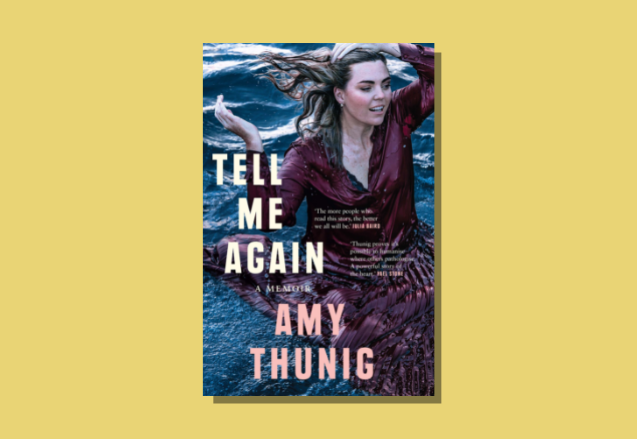

This is an edited extract from Dr Amy Thunig’s memoir, Tell Me Again (UQ, $32.99), out now

Photo credits: Iron Monkey

No Comments