If you, like me, are worried by the amount of time you spend consuming trash content, then you, like me, might have discovered some podcasts that can help.

In last year’s lockdown, I rewatched all six seasons and two films of Sex and the City. Was I ashamed about this vacuous, hyper-capitalist fashion-fest? No! Because I also listened to the podcast Sentimental in the City, where writers Caroline O’Donoghue and Dolly Alderton dissect the franchise. With the help of over 20 hours of their wit and insight, I successfully convinced myself that Sex and the City was a feminist masterpiece.

There is a steady rise in podcasts offering highbrow analysis of conventionally ‘lowbrow’ content—from O’Donoghue’s Sentimental Garbage and The High Low in the UK, to Australian podcasts adopting the same model, like Shameless or the more recent Unsolicited. There are also sub-genres: the critical study of reality TV, for example, in podcasts like Spectacle and Unreal.

I convinced myself that SATC was a feminist masterpiece

It’s not surprising that these podcasts are so popular: over-intellectualising is a fun game to play. It’s also not surprising that they’re particularly popular with (and almost exclusively hosted by) women.

I think most readers would be familiar with the idea that conventionally ‘female’ interests like fashion, celebrity gossip, reality TV, chick-lit and chick-flicks are more easily dismissed than whatever conventionally ‘male’ interests are, like… well (at the risk of sounding dismissive)… sport? Sometimes, the mere fact that something is popular with women can become a reason to treat it with derision.

A great example is O’Donoghue’s episode on Titanic, which recounts how the 1997 film was an immediate critical success. It was only weeks after release –when it became apparent that the box office returns were owed, in a large part, to a generation of teenage girls discovering Leonardo Dicaprio – that the film’s critical reputation started to sink (sorry, I had to).

The memes flooded in; the door was measured and before long, the most-Oscar-nominated film of all time was a movie most people wouldn’t admit to liking. O’Donoghue corrects this injustice: she treats the film with overdue intellectual rigour and convincingly defends it as a masterpiece.

The most-Oscar-nominated film of all time was a movie most people wouldn’t admit to liking

My only concern is that women (like men) have vast and varied interests, and the tv shows we watch, or the books we read aren’t always going to be of a Titanic-quality. In these cases, I worry that intellectualising the things we love isn’t actually the best (or the most feminist) defence: it’s just another way of being ashamed.

I’ve had friends implore me to watch Desperate Housewives because it’s insightful about race and class and it holds a mirror up to society. This is a common argument used to defend reality tv as an art form. It might well be true, but I dispute that it’s the reason anyone watches reality TV. If it were, we’d binge-watch advertising (show me a better reflection of society’s values than what it tries to sell people and how). This suggests to me that they’re still ashamed of the real reason: they like the feeling of their brain switching off at the end of the day.

I think it was shame, too, that propelled me to think of Sex and the City as a feminist masterpiece. I wish I could’ve taken my cue from the hosts of the podcast themselves, and, instead of whipping myself up into a defensive frenzy, just said: I loved it when I was 14, and that girl is still in there somewhere.

Intellectualising the things we love is another way of being ashamed

Every time we justify our interests based on their socio-political value, we’re arguing on patriarchal terms: we’re accepting that those interests require justification, where traditionally-male interests don’t. Yes, there’s just as much politics in sport as in fashion or reality tv – the cultural diversity; the class mobility; the role major competitions play in global diplomacy. But ask a man why he likes sport, and he won’t stoop to citing any of these reasons. He’s more likely to laugh at the question. This response is, I think, a more graceful defence than even the most eloquent podcast.

It would be a dreary world indeed if everything we loved, we also wholly, objectively approved of: if love ignored or minimised or apologised for imperfections, instead of persisting in spite of them. Or if we only loved what is good for us—if there were no mindless pleasures, only high art and hard exercise.

If we repeat the question—why, why, why—too many times, we’ll feel compelled to answer. And in answering, we risk finding a new, more sophisticated mode of shaming women.

None of this is to say that I’ll abandon any of my over-intellectualising podcasts. I’ll remain a devoted listener, not because they’re good for feminism (although, often they are) but because I love them.

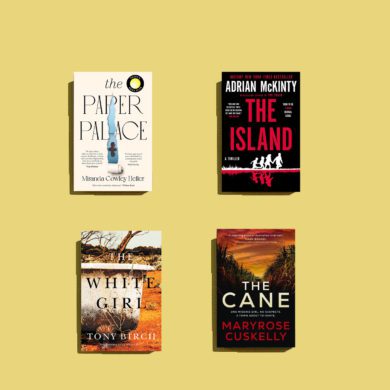

Main image collage by Kylie Hannaford

No Comments