The police were watching Anya Smith. She was sure of it. Why else would the patrol car have cruised past three times that morning already? Moving calmly around her house in the Queensland town of Goondiwindi, she closed the blinds, and waited for her husband Chris to come home for lunch.

As soon as he walked through the door, he realised something was wrong.

“I asked what was going on,” he remembers. “And she told me we were under surveillance. ‘They’ were planning to take the kids away, and one of us was going to be arrested. I tried to reassure her that wasn’t the case, but it didn’t seem to help.”

I asked what was going on and she told me we were under surveillance.

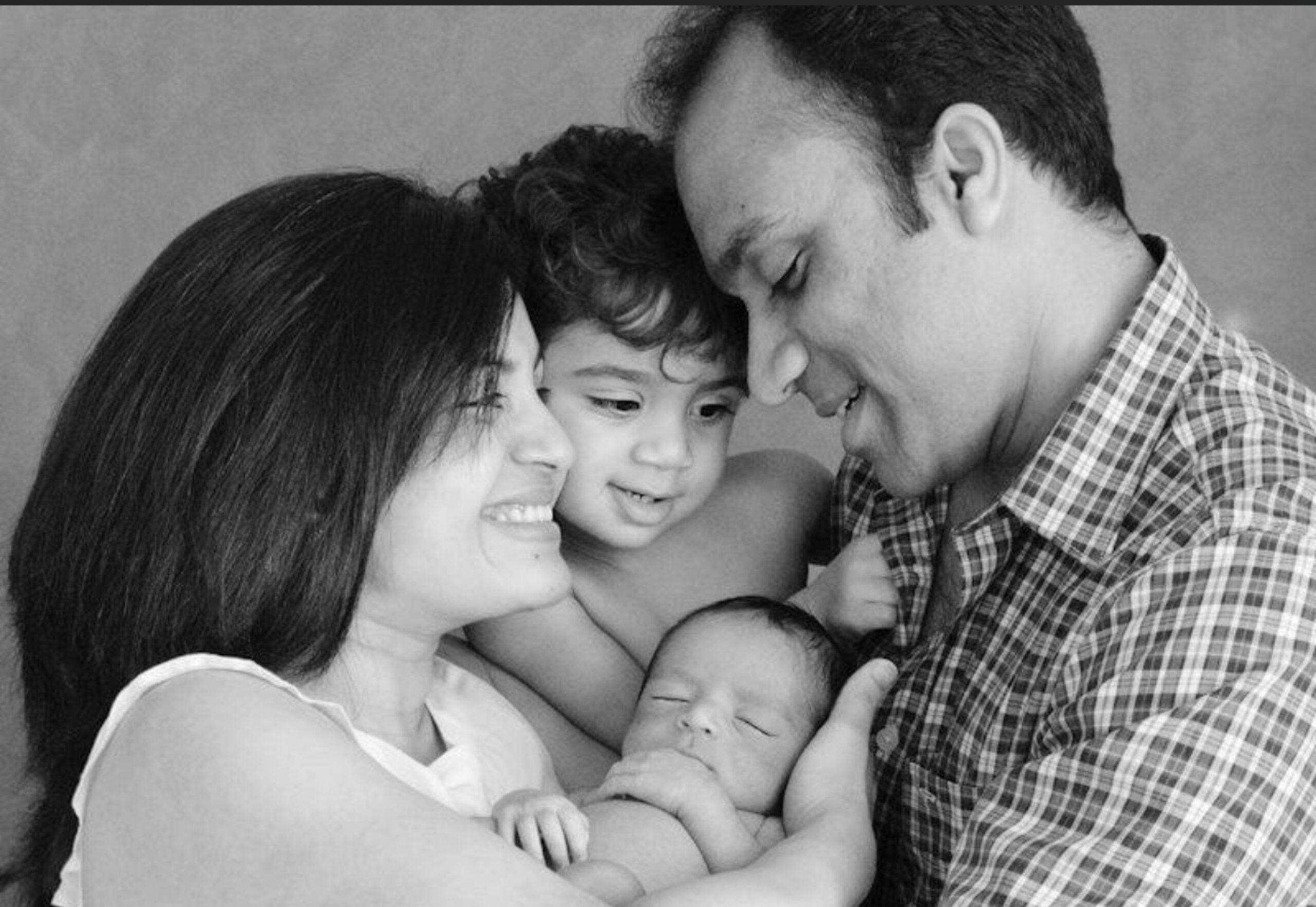

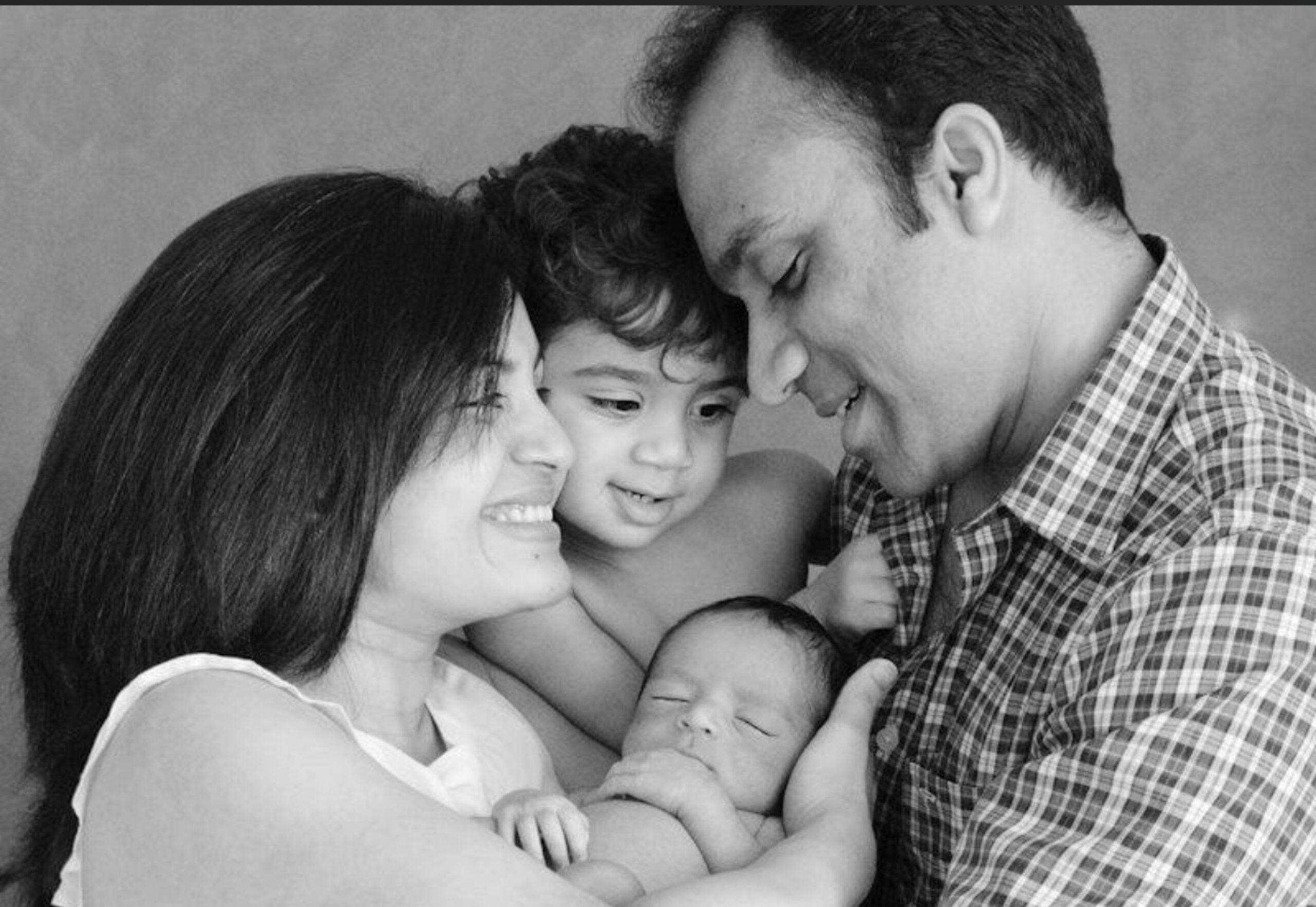

It was August 2019, and three months earlier Smith had given birth to the couple’s second child, Charlie. Although the family was navigating the depths of sleep deprivation, this was their second child and there had been none of the shell shock that came with baby number one.

Two children under two was tiring, but overall things up until that point had been good.

“I’d done it all before, you know?” she says. “It was three months in that everything went pear shaped.”

From then on, her memories are patchy. “They’re more like snippets from a horror movie,” she says.

It was three months in that everything went pear-shaped.

Her husband, however, remembers it vividly. In the days after that first incident, Smith became too anxious to leave the house. She began to make strange comments about her cousin being involved in illegal business. She also became convinced her dad had done something terrible, decades ago, that was about to be uncovered. “It was really out-there stuff,” says her husband, Chris. “In hindsight, I should have sought help earlier.”

When, a few days later, Smith began crying and didn’t stop, her husband became extremely worried. The next morning, he rang a local Child and Family Health Nurse, and asked her to pay a visit to the house. His mum came round to look after both Smith and the children and, it being Monday morning, he left for work.

“The nurse called a couple of hours later and told me to come straight home,” he says. That night, his wife and newborn were admitted to the Brisbane Centre for Postnatal Disorders at Belmont Private Hospital.

Smith was diagnosed with postnatal psychosis, also known as postpartum psychosis and puerperal psychosis. A potentially catastrophic condition that affects women after childbirth, it is very rare. (Although Smith was a nurse, she had never heard of it before.)

Whereas PND affects one in five new mums, postnatal psychosis occurs after no more than two births in every 1000. For most, it will be a one-off episode that, once treated, never returns. For others, it heralds the start of ongoing issues, such as bipolar disorder.

“It usually comes on in a very quick and spectacular manner, within two to three weeks of giving birth, but the onset can also be within hours of delivery or many weeks later,” explains Marie-Paule Austin, head of psychiatry at The Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne, and adjunct professor of Perinatal and Women’s Mental Health at the University of NSW. “It’s characterised by a loss of ability to know what’s real and what’s imagined, which might include paranoia, hallucinations and delusions.”

Some women suddenly believe they or their baby have special powers – or, on the flipside, that they’re evil or defective. Smith’s fear that her little one would be taken is a fairly typical example, says Austin. “I had one case where the mother thought her superiorly intelligent baby had been kidnapped by ASIO and replaced by an inferior child.”

This, in itself, is distressing. But these fears can escalate, leading to the woman’s belief that life, for herself and her baby, is no longer worth living.

That’s what happened in 2021, when Melissa Arbuckle lay down on a railway track in Melbourne with Lily, her three-month-old daughter. The investigation later reported that she thought Lily was suffering from shaken baby syndrome, which would kill her. Both were hit by a train. The baby died, her mum surviving with fractures and internal bleeding. Arbuckle later pleaded guilty to infanticide.

However, tragedy compounded tragedy when in January this year – 18 months after the death of her daughter– Arbuckle took her own life.

“This is why it’s considered a psychiatric emergency that requires urgent medical attention,” says Austin. “Early detection and intervention are crucial for ensuring the safety and wellbeing of both the affected mother and her baby.”

And yet, too often – as with the case of Melissa Arbuckle – postpartum psychosis is not picked up during routine health visits. Even when it is, a lack of dedicated resourcing can mean that women miss out on vital care.

Fortunately for Smith, the visiting nurse recognised the urgency of the situation, and from there, things moved quickly. Later that same day, they were given a bed at a mother and baby psychiatric unit, albeit a four-hour drive away.

There, Smith was prescribed a combination of antipsychotic and antidepressant medication. After two weeks, she was put forward for Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT), which can relieve depressive and psychotic symptoms by passing an electrical current through the brain.

“The stigma around ECT is massive,” says Austin. ‘We can thank One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest for that, which depicted someone having it against their wishes. But modern ECT is a very subtle technique, and it’s incredibly effective for very florid cases of puerperal psychosis.”

As Smith was considered unable to provide consent herself, the decision was made by a panel of experts on the Mental Health Review Tribunal. And so, every Monday, Wednesday and Friday for the next four weeks, she went for ECT, and slowly started to feel more like herself.

“Gradually, I was able to take Charlie in the pram for a walk, and to join in the exercise programs they would run,” she says. “Eventually, I could mix with other people, and function at a more normal capacity.”

After six weeks, Smith was allowed to go home – still medicated, and monitored regularly with telehealth calls.

So, why does postpartum psychosis happen? The headline is, we don’t know, beyond the fact that it’s more common if a woman has previous experience of psychosis or bipolar disorder.

But even among women with no history at all, like Smith, the risk of psychosis striking during the four weeks following childbirth is 23 times higher than at any other stage of her life, says Professor Veerle Bergink, a leader in the field of perinatal mental health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in Manhattan. “We just don’t know why childbirth is such a strong trigger,” she says.

Researchers have considered the role of hormones, hypothesising that the 200-fold reduction in oestrogen and progesterone following delivery may play a part. The effects of sleep deprivation, too, have been investigated, and recent studies have suggested a possible overlap with certain neurological disorders. It seems increasingly likely that postnatal psychosis will be the result of a combination of factors. So far there’s nothing conclusive.

With a relatively small pool of cases to study, it’s not an easy field to research, but that’s not the real obstacle, according to Professor Megan Galbally, director of the Centre of Women’s and Children’s Mental Health at Monash Health. “Investment in research and treatment is crucial,” she says. “But there is an increasing awareness that women’s health – including women’s mental health – has not been given the priority in research and clinical funding.”

Professor Bergink agrees, flagging that in the US, where she’s based, postpartum psychosis isn’t even listed as its own condition in the DSM-V (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition). “We’re not getting any closer to an answer,” she says, bluntly. “First, this disease has to be officially classified, so that research funding becomes available.”

As frightening and destabilising as Smith’s experience was, for her, the system worked. When it doesn’t, things can be much worse.

Priya Naik had her second child in July 2015. Softly spoken, with neatly painted nails, she runs a dental practice with her husband, Mithun, in Bendigo. She had been planning to take at least six months off, but when the dentist they had hired as her cover fell through Naik saw no option but to return to work early.

“So, I had Yohan in July, and went back to work in September, full-time,” says Naik.

It was challenging from the start, working all day and feeding Yohan through the night. Soon she felt overwhelmed by an anxiety she had never experienced before, followed by a series of unsettling episodes and unanswered pleas for help.

“I started having racing thoughts that I couldn’t stop,” she says. “I’d sit in a corner on the carpet and write them down, hoping that if I lost my mind, someone would be able to understand what had happened.”

One entry explained that their house, bought when the previous owners divorced, was filled with grief, and the only solution would be to give it away. Another included details she’d imagined of a friend’s plan to hang himself, which, unless she prevented it, would be her fault.

Naik contacted her obstetrician, who gave her the number for a nearby postnatal support centre. “I called and told them, ‘I’m scared I’m losing my mind.’” They didn’t call back.

Next, she visited her GP, who advised sleeping tablets. “Looking back, I remember being quite composed. Maybe I didn’t give her enough to believe there was something truly wrong,” says Naik, generously.

Looking back, I remember being quite composed.

By the next morning, she was sobbing uncontrollably and unable to sit upright, so her husband took her back to the GP. Shocked by the rapid decline, she sent them to Emergency, where Naik was deemed in need of in-patient care, but sent home anyway. “A nurse told me, ‘We’re trying to get you into a Mother Baby Unit, but there’s no rooms available, and we don’t want to send you to the adult psychiatric unit. It’s not nice in there.’”

Unsurprisingly, her deterioration continued at home. Two days later, a visiting case worker made the decision it wasn’t safe for her to remain there. They directed her back to Emergency, and from there she was admitted to the adult psychiatric unit.

“It was chaos in that place,” says Naik, crying quietly. “Everyone would wander around doing their own thing, right outside your room. Men and women. They were all suffering, all disoriented… I’d just stay in my room as much as I could.

“To be away from my baby when he was so young…” she continues. “A new mum is too vulnerable to be in an adult psych ward. It’s horrible.”

Whilst there, her family felt her condition was worsening. Once, she passed out from too high a dosage of medication. After three nights, she refused to stay any longer. Amazingly, she was discharged.

The room at the Mother Baby Unit never materialised. Since then, Naik has been diagnosed at various times with bipolar disorder and depression, and has spent the eight years since struggling to find the right balance of medication. “It’s only in the past 18 months that I’ve felt present, instead of like I’m walking through a fog.”

She feels certain that had she been admitted to a Mother Baby Unit, her road to recovery would have been less bumpy.

Julie Borninkhof, CEO of Perinatal Anxiety & Depression Australia (PANDA) agrees. “Mother Baby Units are contained, targeted mental health units where women are going through a similar experience, age and stage, rather than being included in the whole community that you’d find in a general in-patient facility,” says Borninkhof.

“They can be having their medications managed, but still breastfeeding and building confidence with their baby. We need that to be occurring, because mums will not engage if they feel they need to put their mental health ahead of their babies, by leaving them with others.”

Unfortunately, these purpose-built facilities are scarce. To cater for the number of perinatal mental health issues that occur in Australia, Megan Galbally says we should be aiming for one eight-bed Mother and Baby Unit (MBU) for every 15,000 deliveries.

That guideline, set by the UK’s Royal College of Psychiatrists, and used as a reference point by The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, would equate to 168 beds, spread across 21 MBUs. Instead, there are only 83 beds, between 13 units, chiefly in metropolitan hubs.

“The system is fairly chockers,” confirms Borninkhof, “and mums in regional and remote areas struggle the most to access these units.”

It’s only in the past 18 months that I’ve felt present, instead of like I’m walking through a fog.

The bigger problem, though, is our general lack of awareness around postnatal psychosis. For a long time, it was considered too alarming a condition to discuss with parents-to-be, since it’s so rare. Even today, there are health professionals who feel that way. But, clearly, if people don’t know it’s a possibility, they also won’t know that it requires urgent attention. And in Naik’s case, that ignorance extended to the string of doctors who dragged their heels when she reached for help.

“It’s a bit of a patchwork,” admits Austin of the medical community’s level of awareness. “It really depends where you are. Some places have extensive training in perinatal health. Others don’t.

“There’s also the issue with psychosis that it does wax and wane, especially at the start,” she continues, so it’s possible that a sufferer may appear totally normal at the time of an assessment. “Meanwhile, at the back of most women’s minds is, ‘If I show that I’m not coping, they’ll take the baby away.’ That layer of stigma may delay the obvious onset to clinicians or family.”

Naik is keen to dispel that stigma, so that others in her situation are prepared. “The mind is just another organ, so why does it have to be so taboo?”

Borninkhof from PANDA agrees. “As a culture, we set people up to think motherhood is going to be smooth sailing, that anyone can do it, because we’ve been doing it for thousands of years,” she says. “We need to open up the conversation about perinatal mental health, including postnatal psychosis, not so that people fear what might happen, but so that they know the support is there, in the event that they do become impacted.”

It was that same knowledge – of what might happen and how it can be tackled – that gave Anya Smith the confidence to continue growing her family. She knew the stats: if you’ve had postnatal psychosis once, there’s a 50 per cent chance you’ll experience it again following childbirth. She also knew that with enough support and the correct medication it could be managed.

Smith says she was “watched very, very closely” by her psychiatrist and GP, throughout the pregnancy and well beyond. When she began suffering from pre-natal depression 12 weeks in, it was identified and treated swiftly. Still, when Angus and Charlie were joined in 2021 by little Monty, everyone held their breath.

“We didn’t consider ourselves in the safe zone until Monty reached the 18-month mark,” says Smith. “He’s two now, and we’re grateful every day for our three busy boys. We know how close we came to having it all taken away from us.”

They were lucky. But it shouldn’t come down to luck. Awareness needs to be raised among health professionals and expectant parents, and investment into research and treatment prioritised, say experts. Until then, says Veerle Bergink, “This is an unacceptable tragedy for the patients involved.”

For more information on PANDA services, visit panda.org.au or call their national hotline on 1300 726 306.

No Comments