Welcome to the battle of the prize-winning books. With just a few days until the winner of the Man Booker Prize is announced, we’ve rounded up and reviewed some of the best prize-winning books of 2020. Happy reading!

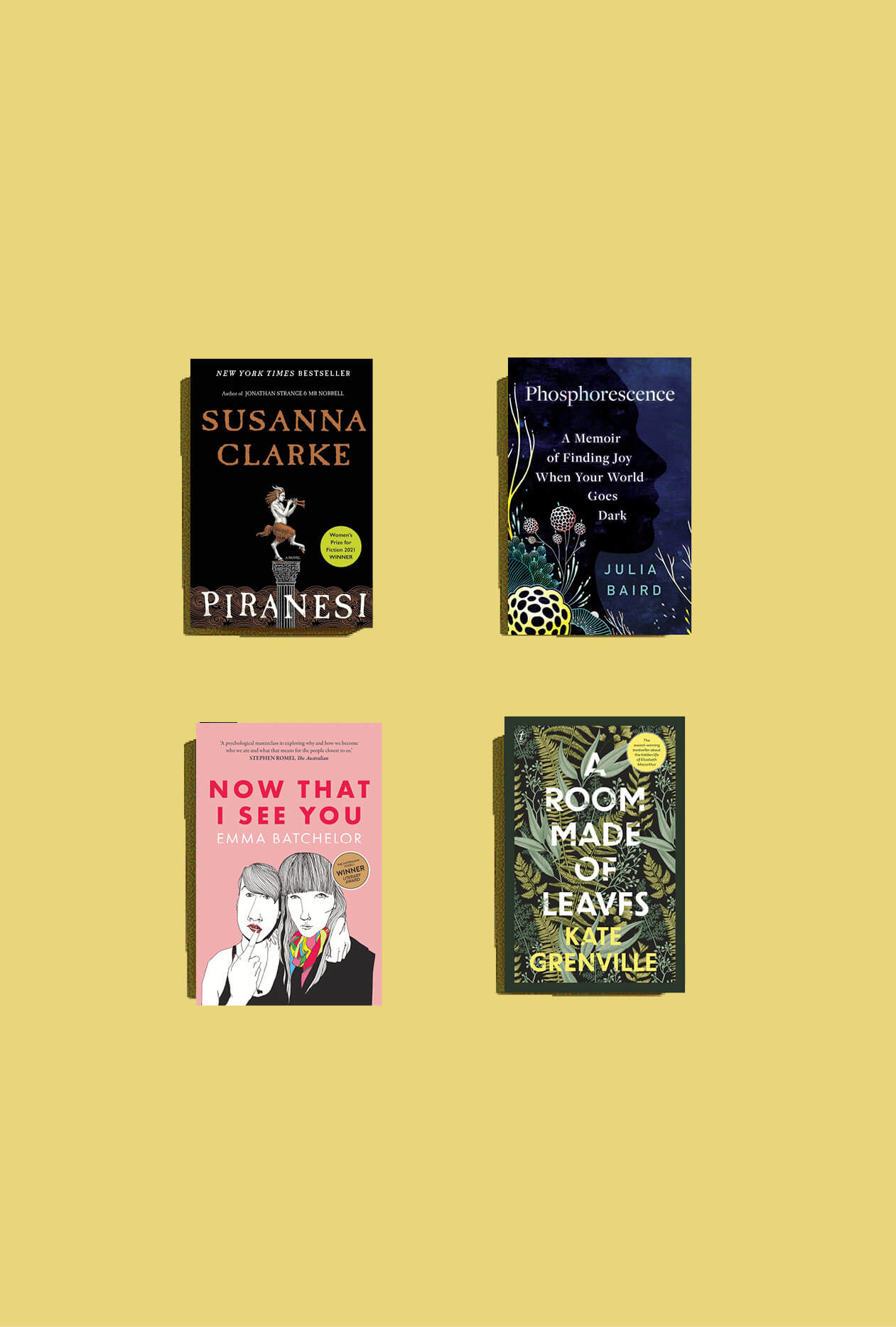

Now that I see You by Emma Batchelor

Winner: the 2021 Australian/ Vogel’s Literary Award

Reviewed by Lauren Sams, author and fashion editor of the Australian Financial Review

I am too old. This is my first thought as I plunge into Emma Batchelor’s Now That You See Me. The story, written as auto fiction – that is, fiction that is very close to the author’s own life – follows Jess and an unnamed protagonist, who is, ostensibly, Batchelor herself.

They are young, they are in love, they have a mortgage. So far, so the Australian dream. But things are not what they seem. Jess is more comfortable dressing as a woman. He changes his pronouns. He explores the idea that he is trans.

Batchelor was in a relationship like this, where her partner revealed truths about his sexuality and identity she had not known, and this story is an exploration of what it means to be young and in love, and the grief of having your life change in an instant. I feel certain it will resonate with many readers.

For me, it did not. Batchelor’s unflinching perspective is refreshing and provocative. But there is so much rumination, so much hand-wringing. I am too old, I think, to read the same thought on repeat. That said, I believe fans of Sally Rooney and Pandora Sykes’ non-fiction will enjoy it: there are parallels to that sense of endless exploration here. It isn’t for me; that’s ok. I am, as we have established, too old.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

Winner: Women’s Prize for Fiction

Reviewed by Sheree Strange, writer and book reviewer at Keeping Up With the Penguins

It’s hard to recommend Piranesi, the long (long!) awaited second novel from Susanna Clarke, without saying too much. This is a book best enjoyed when you know as little as possible going in. It runs just 200-odd pages, styled as journal entries written by a man who lives in a house so large it has its own weather systems. He is almost entirely alone in the house, save for weekly visits from a man he calls the Other.

It seems, at first, like standard light fantasy fare, but the story takes a turn half-way through that will bring it much closer to home in the most unexpected way. Piranesi is a peculiar but brilliant book, one guaranteed to stay with you.

Phosphorescence by Julia Baird

Winner: Book of the Year, Australian Book Industry Awards

Reviewed by Naomi Chrisoulakis, freelance writer

If I read another self-help quote – or worse, whole book – expounding the ways of love and light, I may puke. So I was a little nervous to pick up this book from veteran journalist and host of ABC TV’s The Drum, Julia Baird, about exactly those things. Sure, I’d loved her biography of Queen Victoria, and I also appreciated her journalism, but this exploration of what makes us quietly happy, and keeps us that way when life throws us curveballs, threatened to be a bit… earnest.

I needn’t have worried. This book, which dips into memoir, self-help, science, theology, family, Indigenous culture and sea swimming, is luminous and clear-sighted. Baird, who has been through cancer and a divorce, explores modern life with unpretentious intelligence and gentle good humour. I found it so inspiring, I had to put it down halfway through and fling myself into the ocean, as per Baird’s daily habit. And I think I’ll be flinging myself back into this book again in the future.

A Room Made of Leaves by Kate Grenville

Winner: Christina Stead Prize for Fiction

Reviewed by Sheree Strange, writer and book reviewer at Keeping Up With the Penguins

A Room Made Of Leaves is Kate Grenville’s imagined memoir of Elizabeth Macarthur (1766-1850), a woman largely forgotten by history. Where Elizabeth is remembered, it is only as “the wife of wool baron John Macarthur”. Grenville proves she was, or could have been, much more than that.

She traces the history of young Elizabeth Veale, who married the pompous, volatile Macarthur and followed him to the penal colony of Sydney Town.

At first I was intrigued, then I was enthralled, and by the end I felt as though Elizabeth had been a flesh-and-blood friend. Her story makes for a powerful interrogation of femininity, patriarchy, and colliding cultures. Grenville dedicates the book “to all those whose stories have been silenced”, and it speaks to those gaps in the archive–a stunning work of historical fiction for the #MeToo era.

Winner: The Stella Prize for Women

Reviewed by Anna Saunders, co-founder PRIMER

I tend to approach prize-winning books with trepidation, worrying they might end up too dense or turgid to enjoy. The comments from The Stella Prize judges – explaining that The Bass Rock “will challenge and test the reader” – did little to allay my concerns.

Happily, my fears were misplaced. From the outset, The Bass Rock is a page-turner, following the lives of three women – Viviane, Ruth and Sarah – who all live in the shadow of the huge Bass Rock, on Scotland’s rugged coast, but at different periods in time.

But the Bass Rock is not the only menacing presence in the women’s lives. The thread that connects all three stories is the constant and ancient threat of male violence. The Stella Prize judges were right: this will be a challenging read for many (it opens and closes with attacks on women) but it is also one of the most thought-provoking and beautifully written novels I’ve read in years.

The Animals in that Country by Laura Jean McKay

Winner: Victorian Prize for Literature, and Arthur C. Clarke Award

Reviewed by Sheree Strange, writer and founder of Keeping Up With The Penguins

When I reviewed The Animals In That Country for PRIMER late last year, I observed how eerily prescient it was. Every reviewer did: the novel centres on the outbreak of a highly infectious subtype of influenza that threatens the very fabric of society.

Twelve months later, we’re emerging from lockdowns (societal fabric largely intact), and McKay is celebrating an embarrassment of awards and nominations, all richly deserved.

Her novel is told through the eyes of Jean, a no-nonsense, foul-mouthed grandmother who is forced to leave her remote wildlife park after the aforementioned mysterious flu infects her son, Lee. Those infected develop the ability to communicate with animals – and what the animals have to say is sending them mad.

This is no Charlotte’s Web, but for a dystopian novel it’s oddly uplifting. Reading it reminded me that opportunity can arise from hardship, and reignited my hope that some good might come of it all.

No Comments