For the past 10 years, I have lived on the kind of street that New York City real estate agents like to call “transitional”. New craft coffee shops and sneaker boutiques pop up by the week, but the patch of sidewalk closest to my front door remains a hangout for residents from a nearby men’s shelter.

For as long as I have been here, some part of me has feared these men, almost all of whom are black. I have shown them this fear in myriad small ways. I have turned my gaze toward the pavement or studied my phone to avoid interacting with them. I have crossed the street.

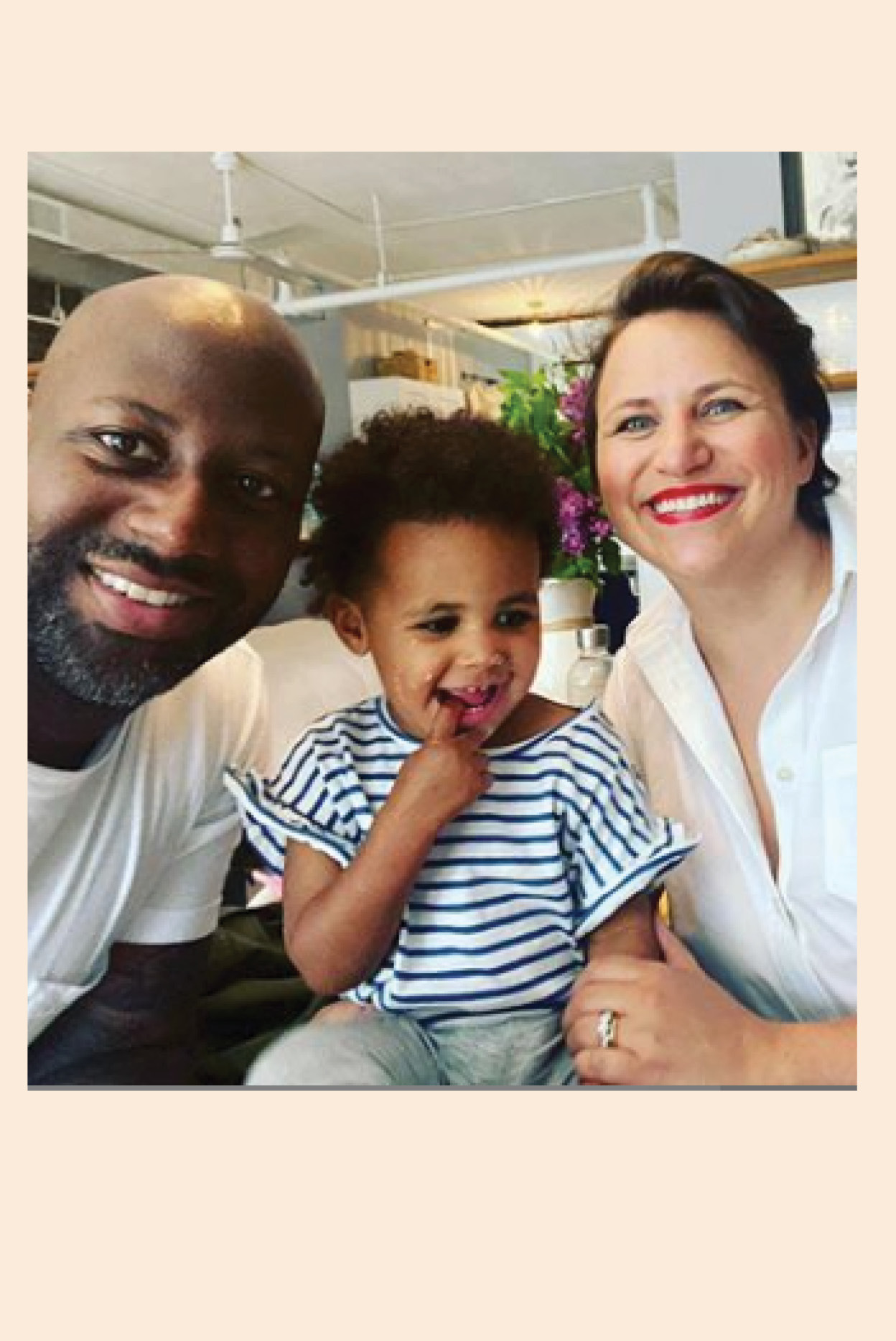

This may come as a surprise to people who know me, because in our home just a few metres away, live the two most important people in my life—my husband and our young daughter—-and both of them are black.

When people ask my husband, Jordan, and me whether it’s an issue in our marriage, I always give the same answer: oh, yes. Big time. Not his race so much, though. Just mine. And not because society doesn’t accept us or because our families don’t get along or any of the stuff you might think would make it difficult. Race is an issue in our marriage because as a white woman of privilege, I have racist tendencies written in at a cellular level, and that can really gum up the works. Let me try to explain.

Take this recent fight we had.

We were headed out of the city to look at holiday properties. Our daughter was asleep in the back seat of the car. Things were peaceful. I mentioned, casually, that our car registration would expire soon and that I needed to remember to call the DMV to deal with it next week.

Jordan lost his mind. Actually, let me say this one more time, just to make sure you really get my meaning here: Jordan. Lost. His. Mind.

He asked how long I had known about the expiring registration, and why I hadn’t done anything about it. He lamented the fact that we were keeping a car in the city in the first place, and complained that I hadn’t kept him in the loop on the paperwork.

It only escalated from there.

I could not for the life of me figure out why this was such a big deal. I told him to stop yelling, to be a bit nicer. What was the fuss about? I would get it taken care of. Jeez.

And then he said it.

“G, do you realise that if we get pulled over for these goddamn plates, I could get killed.”

No, actually. I had not realised.

Because when I get pulled over, the cops smile and ask me if I know my tail light is out.

Because I have the kind of body that police in America think they are supposed to protect, not to protect against.

My marriage contains too many stories like this one. Times when I assumed that the way I experienced the world was the way the world was, full stop.

I now know that the world treats me differently to my husband.

I now know the world treats me differently to my husband

It is the same way it treated our parents before us, and their parents, and so on and so forth. The same way that it will treat our daughter. That generational trauma – or lack thereof – is a central character in the story of our lives. In order to be good partners to one another, we’ve really had to learn how to make room for this difference, and to metabolise and correct the pain that it causes.

I confess that I did not see these issues coming. I have long been a member of what Jordan calls “y’all progressives.” I worked in the media for years before quitting my job to join Hillary Clinton’s campaign in 2016. Later, I helped organise the Women’s March. In New York City, where we live, interracial couples are everywhere. Jordan wasn’t the first black man I’d dated, and I wasn’t the first white woman he’d dated. We were not special. We were not even a blip on the radar.

For all of these reasons, I long considered myself immune from the racism and white supremacy that I have spent so much of my life raging against.

I was wrong.

This past Christmas my family and I were spending a few days with my mother in the upscale gated community where she spends her winters. It’s a lovely, manicured place with special lanes for golf carts and overly manicured lawns and a metric tonne of white people. During dinner one evening, my mother’s neighbour stopped to deliver a box of biscuits and to loan us a pot. While fawning over our daughter (an understandable reaction, considering she is the cutest creature in all of creation) she said to her “What a wonderful, adorable little Mutt you are.”

A Mutt.

There aren’t really words to describe what it felt like when that word hit the air.

Jordan and I locked eyes, and I could feel the words moving between us. Was he going to say something? Was I?

And then the moment was over.

Later that evening, Jordan and I fought. He felt like I had prevented him from defending his family. I felt as though the woman – someone who had shown my mother real kindness over the years – had probably meant no harm. “She was trying to tell us our baby was cute,” I said, “She just didn’t know any better.”

Technically, I never told Jordan not to correct that woman, but everything around him – the house, the company, the community – was sending a clear message: We all mean well here. Do not rock this boat. And I was right there along with them, centring a white woman’s comfort – and my own impulse to keep the peace – ahead of what my family needed.

It has been six months since that night and I still think about it almost daily.

My daughter. The one human I would eat glass for.

My husband. A man whose side I vowed to be on.

I failed them that day.

Maybe the woman intended to say something racist to my daughter, and maybe she didn’t. But the intent of her words does not erase their impact.

I had an opportunity to gently dismantle a racist situation, and I did not not take it. I will spend the rest of my life trying to understand why.

Here is what I have come to understand: White supremacy does not mean that *I* believe that white people are the superior race—it means that our entire world has organised itself in a way that suggests that to be the case.

Everything we have ever learned—from the way we are educated to the television shows and sneaker ads we watch to witnessing who gets which seat on the bus—has sent the message to white people that they are right and powerful, and that everybody else is secondary. And the “everybody else”? They heard the same messages.

Everything we have ever learned has sent the message to white people that they are right and powerful, and that everybody else is secondary.

I am telling you, this stuff runs deep. As a white American woman, I have too often made the mistake of considering racial injustice as something happening to black people that I needed to empathise with and fight for, instead of understanding it as something that I myself was creating and responsible for.

And if I want to show up fully in my marriage and as a mother—which I do—then I have to commit to excavating and disassembling this belief system in myself first.

When Breanna Taylor and George Floyd were murdered by police violence earlier this summer, I struggled to know what to do. Protests erupted around the city. Our apartment – close to New York’s City Hall – rings daily with sounds of uprising. My daughter, who has recently learned to say, “Put your mask on, there is a virus outside,” now opens her curtains in the morning to say, “Good morning, protesters”.

So, I opened up my instagram account and started to write. Over the past few weeks, I have been sharing stories of the ways that race impacts my marriage, and the ugly truth about all the mistakes I have made – the lessons I have learned the hard way, and the work I know is yet to be done.

It is excruciating, and I am often very, very ashamed of what I uncover. I understand that the world may have given me a privilege and a lens, but I also know that I alone am responsible for fixing it. I have work to do. As we make our way through what could be the hottest summer in american history—the pandemic, the uprising, the election—I hope that this can help you see that you, too, may well have work to do.

You can follow Genevieve on Instagram here or at her social impact and culture change agency Invisible Hand

Want more stories like this? Sign up to PRIMER’s weekly newsletter here.

2 Comments