I step out the door with Marc, my 16-month-old son, strapped to my chest in the Baby Bjorn, writes Luke Benedictus, above. The winter chill makes him frown and he huddles in closer. By the end of the road, he’s slumped against me fast asleep, lulled by the undulation of my breathing and the steady motion of steps as I cradle his beanie-clad head in one hand.

I keep walking. Life with Marc and Joe – his two-and-a-half-year-old brother often resembles a slapstick disaster zone. But this sensation of a sleeping child on my chest brings a welcome sense of calm. I turn right and trudge up the cliff path in the hope the lack of traffic will keep him asleep.

Frankly, I don’t know if my father took me out like this when I was Marc’s age – he died of cancer when I was 11. Since becoming a parent myself, I think of my dad a lot and regret that I never got to know him better. What I do know is that I’ve had the opportunity to be a lot more involved in my kids’ lives than his generation of fathers ever did. Dads today are expected to be way more than breadwinners and disciplinarians – it’s assumed we’ll be deeply entangled with the chaos of their daily lives. We’re lucky to have that chance, too. It offers us the opportunity to build a deeper connection.

As I was still only a kid when dad died, I never got past that stage when you think your dad is a superhero. My father took me to the football, taught me how to play chess and to never trust any man with two first names (sorry, Adam Scott). But reflecting on that loss also makes me consider how I want my two sons to remember me.

It’s a massive question. But when I ponder it, I can’t really get past this moment on the cliff with Marc. I love how, whenever he’s wedged into this papoose, he instantly feels so comfortable and secure that he falls asleep in minutes. He’s happy to just let go, safe in the knowledge that I’ve got him.

And as my sons grow up – through school, teenage angst and beyond – that’s the way that I hope they’ll always feel about their dad. To continue to stay relaxed in my presence, forever trusting, completely at ease. I hope they’ll always feel as close to me in the future as my youngest son is right now, drooling against my chest in his sleep.

“We have the freedom to choose to do fatherhood differently”

Christopher Scanlon, above, is a Melbourne-based journalist and author of YA fantasy novels The Chess Raven Chronicles, co-written with his wife Kasey Edwards under the name Violet Grace. They have daughters aged five and 10

Sitting in the hospital 10 years ago, holding my daughter when she was less than an hour old, something clicked inside me. I had a sense of calm focus, a shift as the reality of fatherhood settled on me.

I was now responsible for a little girl who was so precious and beautiful it robbed me of breath. I wanted to give her everything, and that included being the best possible dad.

I was in the fatherhood lane. And while I was absolutely certain this was the right path for me, I felt like I was driving without a licence.

A lot of time and energy had gone into her conception through IVF, but it occurred to me just how little thought I had given to what sort of father I was going to be.

My own experience of being fathered wasn’t much preparation. While my dad and I have a deep and respectful bond, we have never had any deep and meaningful conversations about fatherhood.

That’s not a criticism of him. He’s from a generation of men for whom fatherhood was what you did once you reached a particular stage of life. Fatherhood was about being a good provider, a role he fulfilled by working a job he hated for most of my life.

I wanted to give her everything, and that included being the best possible dad

More generally, fatherhood isn’t something we as a culture spend much time reflecting on. Unlike motherhood, which seems to be scrutinised constantly, relentlessly, fatherhood slips under the cultural radar. There are few male equivalents of “bad mothers”, “yummy mummies” and “tiger mums”, for example.

And while my wife Kasey built up a network of emotionally supportive mother friends during IVF, her pregnancy and over the years, I have no fathering equivalent. My conversations with fathers rarely get past the ‘how are the kids?’ small talk.

When I look for examples of fatherhood outside my own dad, there are none I particularly want to emulate. The media gives us ‘clueless’ dad (think Homer Simpson) or old-school ‘authoritarian’ dad; even the new cool dad you see in ads — mostly for clothes and family cars — seems one-dimensional and bland.

But perhaps the lack of cultural scrutiny is an opportunity.

As well as avoiding the constant analysis and judgement that mothers have to endure, fathers have the freedom to choose to do fatherhood differently, and redefine it as we — our kids and our partners — need us to.

For me, that means parenting equally to my wife, showing to my daughters Violet and Ivy that they should expect equality and respect from boys and men, especially as my eldest enters her teenage years. My model of fatherhood is to be an interchangeable carer and nurturer with their mother, not just a disciplinarian or a playmate.

Every generation of fathers has the chance to be a new kind of dad. While we might not have many great scripts of fatherhood, we each have the chance to write our own.

……………………………..

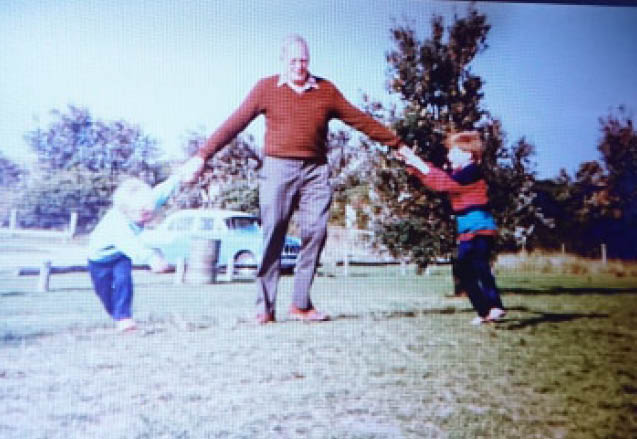

“I hope my children’s experience will mirror my own with Grandpa”

Ben Hobson is an author, whose new book, Snake Island, is out now. He and his wife Lena have two sons, Charlie, aged six and Henry, four

I cried this year watching a video of my grandpa. I only have blurry memories of him. I was young when we were mates, and as I grew up I committed that awful sin of so many teenagers in becoming completely self-involved. I stopped visiting him, listening to him. I’m in my 30s now. Grandpa passed away a few years ago in a retirement village.

Mum had hired a you-beaut video recorder from a town 40 minutes drive away. So she could wake up early and go and get it, she had us sleep over at our grandparents’ place. As they dropped us back home in the morning, she was already filming.

Grandpa had built some stilts. They were as tall as an adult, and had little steps on each side you put your feet on to stand a little taller. They had sharp points on the ends to help divot each step into the earth. He retrieved them from the boot of his car, looking a tad awkward in front of the camera.

I was racing around Grandpa’s feet, climbing up him, climbing up the sticks. I hadn’t even started primary school yet. He was so patient. There wasn’t a cross word. This wasn’t a task that needed to be completed. He wasn’t just ticking a box and moving onto the next thing – something, in my busyness, I find myself doing far too often with my own children.

He was simply giving me space to discover what these were. As I struggled up, he lifted me, his hands under my arms. He held both sticks steady over my own small hands and then he helped me lift my foot, lift the stick, pretend to be a giant. Standing behind me, encouraging me. I moved with joy and laughter, him doing most of the work.

I had no memory of this happening while watching the video, crying. But that doesn’t matter. What matters is it did happen. What my grandpa gave me then has not been erased because I forgot about it. My children are the age I was in the video, right now. I know they’ll forget many of the things I do for them. But their experience of their father will hopefully mirror what I saw. Someone who had, at that moment, all the time in the world to play, who held that little boy on stilts with endless patience and infinite love.

No Comments