It began last week, the way so many of these things do, with a tweet from a small, individual account. A user named @julianprjhad noticed a discrepancy between the height of cricketer Ellyse Perry in real life, and Ellyse Perry on the cover of The Australian newspaper. In real life, Perry is roughly five centimetres taller than David Warner, the former captain of the men’s cricket team. But on the front page of The Australian,in a report about the Alan Border medal, it appeared that their heights had been altered so that Warner was taller.

So,@julianpri tweeted it. From there it was retweeted and then picked up by Melbourne writer and broadcaster Jess McGuire, who has nearly 13,000 followers, and tweeted:

“The Australian fixed the proper order of things, man towering over woman, very good.”

Then the real pile-on began. Within 24 hours it had been retweeted nearly 3000 times and liked by 13,000 people before making the jump to Facebook, Instagram and then news outlets.

Comments abounded. Was masculinity this fragile? Was The Australian, which has already been chastised for its conservative approach to news, this sexist? More to the point, were they this dishonest? By the time the viral tweet reached the newspaper itself, a denial was issued from its sibling website, News.com.au. Nothing to do with height, the reporter assured readers. Just a case of deep etching of photos and graphic design. Just the day before, the journalist pointed out, Scarlett Johansson was pictured towering over Al Pacino.

And while some still refused to believe this explanation, it’s indicative of the world we now inhabit that an explanation was issued at all.

Welcome to Call Out culture, where no one is safe from making a gaffe and being pilloried for it on social media. Just ask J.K Rowling, who was called out for what many viewed as a transphobic tweetin December.Or Taylor Swift, who cancelled her appearance at the Melbourne Cup last year amid intense criticism from animal rights groups.

Call Out culture has even spawned an entire sub-genre of Instagram accounts devoted to calling out fashion and beauty brands, like Estee Laundry (155,000 followers) and Diet Prada (1.7 million).

“Everyone has an audience and a loudspeaker, we are never switched off anymore,” explains Vanessa Gerrie, an academic who has researched call-out culture as it intersects with fashion. She says that in today’s social-media-fuelled climate, ‘woke’ or progressive ideas carry “social-cultural cachet” and tend to spread particularly fast.

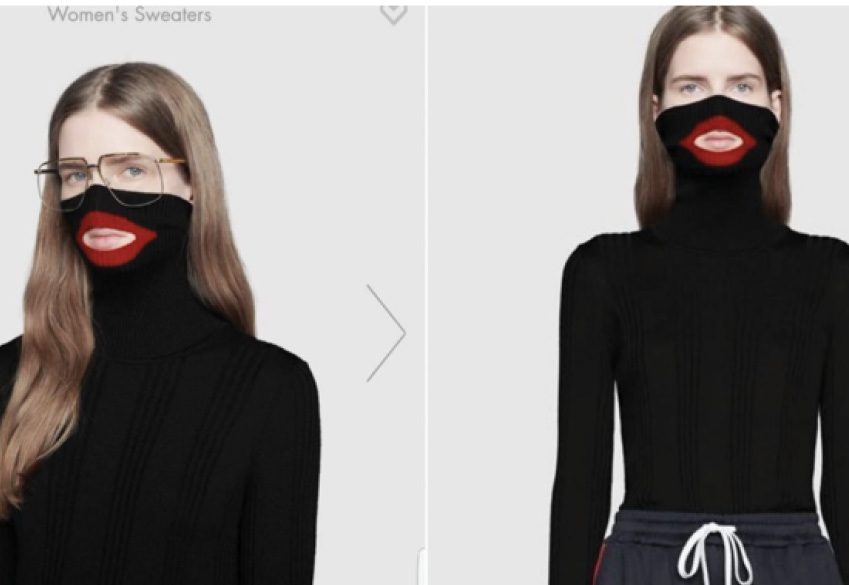

This can be enormously powerful. After all, it’s call-out culture that delivered us #MeToo, #TooStrongForYouKaren and most recently #OscarsSoWhite. In the fashion and beauty worlds, Estee Laundry and Diet Prada have shone attention on diversity issues, greenwashing, deceptive practices and copycats. Just last week, Estee Laundry called out makeup remover brand Face Silk for copying the branding of brilliant Australian makeup remover, Face Halo, while last February, Diet Prada took on Gucci over a balaclava that resembled blackface, and the criticism became so widespread that the fashion house released an apology and recalled the product.

In 2018, Diet Prada called out Stefano Gabbana, after the designer allegedly posted racist remarks about China to his Instagram page. The result was a cancelled multi-million dollar Dolce and Gabbana show in Shanghai.

Gerrie says these examples prove that collective protest can instigate incremental change. “Some of these businesses are making moves or at least they seem to be listening” she says.

Although, she cautions, “It is hard to know whether these gestures are tokenistic or genuine. Things such as diversity and sustainability and the image of them are capital for these businesses, so as consumers of product and media we have be attentive.”

Cancel culture, says Gerrie – the darker, more destructive sibling of call-out culture – happens when dialogue ends. “Calling out a brand or an individual for behaviour or opinions can enact change if it instigates critical reflection and conversation. What often tends to happen however is that the one calling out often doesn’t want actual engagement, they want the superficial clout [that comes with pointing out others’ weaknesses].”

That hollow smugness associated with keyboard warriors is something even President Obama has weighed in on, pointing out in October that self-satisfaction was no substitute for meaningful dialogue or action. “If I tweet or hashtag about how you didn’t do something right, or used the wrong word or verb, then I can sit back and feel pretty good about myself, because, ‘Man, you see how woke I was. I called you out.’’ That’s not activism.”

In what some saw as a deliciously ironic twist, Obama was promptly called out for those comments by Ernest Owens, who wrote in the New York Times that “Old, powerful people often seem to be more upset by online criticism than they are by injustice.” According to Owens, cancel or call-out culture is just another way to protest and stand up for the marginalised, for whom traditional channels of social justice – the police, courts or even HR departments – have failed.

And that’s the critical point: for call-out culture to have any genuine value, the protest can’t end on social media but go on to incite real-world change, says Gerrie.

Not everyone agrees. Dr Lauren Rosewarne, a senior sociology lecturer at the University of Melbourne, point out that call-out culture can have “educative and remedial properties” even if protests progress no further than social media.

But, she adds, it can easily turn into cyber bullying, which can have catastrophic effects. This is something Welsh author and broadcaster Jon Ronson can attest to. He wrote the 2015 book So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed in which he traced the aftermath of people who had been the victims of social media pile-ons. Long story short: their lives were ruined. In his research, Ronson found that cyber bullying disproportionately affects women more than men.

AmnestyI nternational reports that one in five women feared for their personal safety or the safety of their families after targeted abuse on social media, including doxing (which is when a person’s personal details, including their address and phone number, are made public.)

At its worst, call-out culture, says Rosewarne can make people feel reluctant to engage in online discussions for fear of misinterpretation. “It is also questionable whether being named and shamed actually does anything to correct behaviour or, in fact, whether it makes people dig their heels in.”

That all appears to depend on one major factor: how much capital brands and institutions have to lose.

No Comments