On July 14, 2013, Laura McKowen woke up in a room she didn’t recognise lying next to a person she didn’t know, her phone buzzing with anxious text messages. It was the morning after her brother’s wedding and McKowen had left her four-year-old daughter Alma alone in a hotel room all night while she drank herself into yet another blackout. It was the latest in a string of inglorious episodes, but this time . . . she’d really screwed up.

It wouldn’t be the last time McKowen drank, but it did mark the beginning of a slow and painful reckoning. She quit, for the last time, one year later. Fortified by AA’s 12 Steps, she endured one small milestone after another without alcohol – a Saturday night, a meal out, another wedding – and slowly started to piece together a new life. “In the end, getting sober wasn’t a decision,” she tells me down the phone from her home in Marblehead, Massachusetts. “It was a discovery.”

Words were her ally. She read every addiction memoir she could find and, in turn, began to write, too. “Whenever I wrote a blog post, I’d post it to Facebook and email it to my friends and family. People I didn’t know started getting in touch, telling me how much they related to what I was writing about and asking me to share more.”

In 2015, she established an online platform offering coaching to those in pursuit of a life free of booze and launched a podcast called HOME with Holly Whitaker, the San Francisco-based founder of Hip Sobriety. “We didn’t know what we were doing, but we had a strong sense of a missing conversation around women and alcohol misuse,” she says. “When 150 people listened to our first episode, we were over the moon. That quickly grew to 20,000 a week. That’s when we knew we had an audience.” Today, she has 53,000 followers on Instagram.

We had a strong sense of a missing conversation around women and alcohol misuse

Sobriety and, indeed, temperance are having a moment. And just like the health and wellness “fitspo” movement of a few years back, they have found a home on social media.

Here, influencers such as McKowen, as well as Dawn Nickel of She Recovers, UnPickled’s Jean McCarthy and Lucy Rocca, founder of Everwallpaper, champion the new, counter-cultural cool of abstinence. It’s a compelling proposition, and one underpinned by unvarnished accounts of their own Damascene conversion and pictures of a life that’s not only “hangxiety”-free, but brimming with potential. Don’t think of sobriety as an absence of something, they urge: embrace it as a superpower.

It’s a message that millennials seem only too eager to embrace. According to a survey by University College London, 36 per cent of British 16- to 24-year-olds in fulltime education are teetotal with some universities now offering alcohol-free accommodation.

Here, one government survey found that 23 per cent of Australians under 30 have given up drinking entirely – perhaps deterred by the heavy drinking of older generations, with all of the emotional and physical consequences it entails.

Professor Dan Lubman, director of Turning Point and professor of addiction studies and services at Monash University says millennials have grown up in a culture that embraces alcohol at every turn. “Drinking isn’t just taking place in pubs now. It’s happening in cafes, cinemas, even school fetes.

“Ambulance callouts for alcohol-related incidents are going up; alcohol misuse costs Australia $55 billion a year; it’s the number one modifiable cause of breast cancer in women – drinking a bottle of wine a week is the equivalent of smoking 11 cigarettes a week in terms of a woman’s cancer risk – and yet there are still no government campaigns warning of the risks associated with alcohol in the same way that we see for smoking or gambling.”

Drinking a bottle of wine a week is the equivalent of smoking 11 cigarettes a week in terms of cancer risk

Perhaps social media’s sobriety influencers are stepping into a public education void? “It’s certainly really good to have people who are in a position to help others starting to ask, do we really have to drink as much as we do?” confirms Lubman.

Influencers, of course, capitalise on the very specific gifts that social media affords: its immediacy, its unparalleled reach – access to a global audience with a mouse-click – and a domain where the veil between private and public is gossamer-fine.

Shanna Whan, recovered alcoholic and CEO of newly minted charity Sober In The Country, is a gifted communicator who knows exactly how to work it – and her message is seductively simple. “I want to see not drinking normalised,” she says. “I dream of the day when a bloke at the bar says ‘No thanks’ to a beer and his mates say, ‘No worries!’ Because, currently, the response is archaic. It’s ‘You can’t trust a bloke who says no to a beer! What’s wrong with you?’ In the bush, a bloke’s only worth how much he drinks.”

She has started a conversation about casual alcoholism among a demographic no-one’s looking at – rural Australians. “We have a unique set of parameters,” says the rural New South Wales native. “Geographical isolation for one and the drought which has raised this issue unspeakably. There are farmers who can’t afford to take a break from the relentless hopelessness of the drought and they drink because it’s the only escape they feel they’ve got. And if you don’t join in, you’re running separate to the herd and ostracised for it.”

When, five years ago, Whan started blogging about her own rock-bottom blackout on Boxing Day 2014, she gave a proud, stoic breed of people permission to open up about their own struggles.

City-based models like AA don’t work in the bush because there’s no anonymity here

Sober In The Country, which now numbers 50,000 followers across Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn, operates a private rural professionals’ Facebook page where 600 men and women can find fellowship, solidarity and support as they start to critically examine the way they use alcohol.

“City-based models like AA don’t tend to work in the bush because there’s no anonymity here,” she says. “It’s frustrating that our city-based politicians are still ignoring this conversation.I don’t think that’s really ok, because they speak often about real initiative support while ignoring an issue that’s right under their noses that we are making serious headway on – because it’s not a vote-getter!”

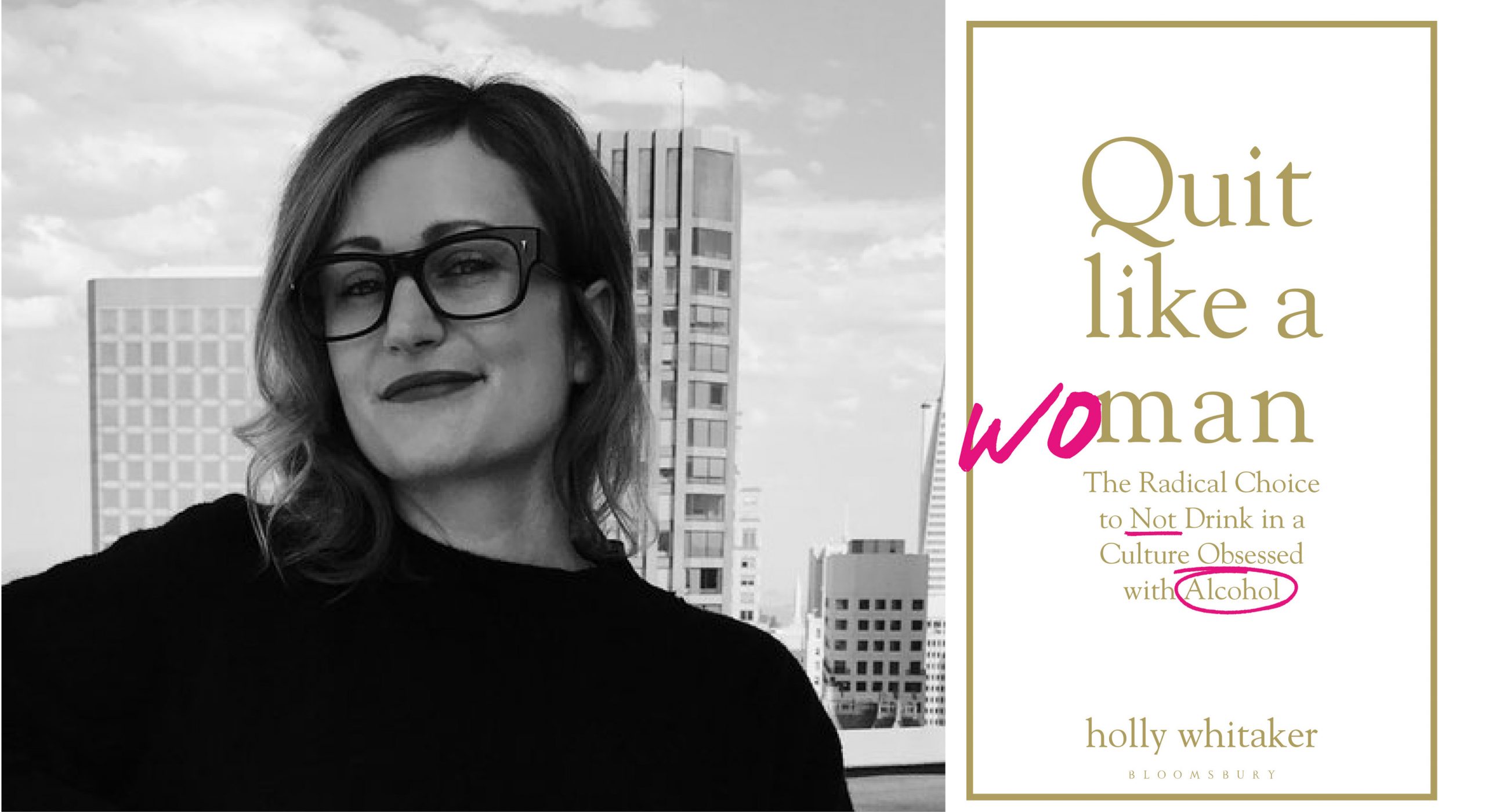

Other influencers also question the relevance of AA in the 21stcentury. Hip Sobriety’s Holly Whitaker – a former accountant who, until January 2013, was addicted to alcohol, nicotine and marijuana – found “working the steps” to be a total non-starter. Not only did she not want to be anonymous, she found its focus on personal defects as the problem rather than the drug itself disempowering. The program, she wrote recently in The New York Times, was created in the 1930s by upper-middle-class white Protestant men to challenge white male privilege and urge followers to submit to a higher authority: how can it speak to modern women?

Instead, she read Allen Carr’s Easy Way To Control Drinking, practised yoga, took hot baths and was inspired, after identifying with beloved writer and activist Glennon Doyle Melton’s Carry On, Warrior, to capture her own experience of getting sober by writing a blog. She decided to “rebrand” alcoholism by co-opting the jaunty Britishism “teetotal”, even designing a cool “Tt” tattoo in the style of a Periodic Table element.

In 2018, Whitaker, who has 84,000 Instagram followers, launched a digital recovery platform spin-off, called Tempest. Its mission? To give followers the tools and the community they need to put themselves at the centre of their own recoveries.

Laura McKowen admits she had a complicated relationship with AA but believes it to be, at its core, a source of “beautiful and timeless spiritual wisdom. It was developed to speak to the person in an acute state of addiction,” she points out, “not to those who just don’t want to drink anymore. We need programs for grey-area drinkers, too.”

Alcoholism has always been a binary construct: either you’re a problem drinker – or you’re not. Increasingly, though, influencers are happy to have a discussion about the many ways in which risky drinking defies clear-cut definition. As they point out, it’s easy to stay in a dangerous place for a long time because what you’re doing doesn’t look any different to what everyone else around you is doing. Just because you have an expensive haircut, drink a kale smoothie every morning and run five kilometres three times a week doesn’t mean you don’t have a problem.

For these “grey-area” drinkers – the “sober-curious” – social media influencers provide the encouragement to try a healthier, more mindful approach to alcohol.

But even influencers admit that there’s a danger that the hardened drinker – or “sober-serious” – who’s relying on an online platform to help lift them out of a dangerous rut might not be getting the calibre of treatment they need. Says McKowen: “[For some people] it’s an inside job that’s going to take a lot of work to overcome. It’s not a light-switch, it’s not cool or fun or sparkly for a while. It’s not about going to a dry bar and ordering a mocktail. But I think that the more all of us talk about alcohol in our lives, the better off everyone will be.”

It’s this sense of positivity and inclusivity that’s at the heart of sobriety influencers’ appeal. “Influencers are very good at reframing quitting alcohol as a win, not a loss,” says Jenny Valentish, Sydney-based journalist, recovered addict, mindful drinker and author of 2017’s Woman of Substances.

“Back in 2008, when I was contemplating stopping drinking, my view was, I’m going to lose my best friend – alcohol – I’m going to lose my actual friends and I’m going to lose my identity as an edgy, hard-drinking journalist. It was going to be my life, minus a whole lot of nice things. Influencers show you how to make your life so much better than it was before.”

McKowen agrees: “I really want people to know that sobriety is an invitation to a much bigger life. In the recovery space, I talk about addiction and sobriety, but I also talk about life, allof life.” The most popular course she offers is called The Bigger Yes, which is all about how to find your purpose in life afteryou get sober. “It asks the question, what do I want to do with my life now that I’ve stopped anaesthetising my pain and anxiety? Those of us who answer the invitation to wake up, whatever the invitation, are really the luckiest people of all.”

We Are The Luckiest: The Surprising Magic of a Sober Life, by Laura McKowen, and Quit Like A Woman: The Radical Choice To Not Drink In A Culture Obsessed By Alcohol, by Holly Whitaker, are both out this month.

No Comments