There’s a scene that has become something of a cliché in popular movie iconography. It’s the one where a married couple has split up and the woman (it is almost always the woman) will throw armfuls of the faithless husband’s clothes out of the bedroom window and then go through their joint photo albums, ripping his head out of every happy, smiling shot.

I was reminded of this when I found myself sitting on the sofa in my flat one evening, flicking through my phone and cropping not my ex-partner’s head, but my own out of a series of wedding photographs. It was a fairly surreal experience excising my beaming face from the pictures, and it was not something I had ever anticipated, because you don’t think about divorce when you’re walking down the aisle.

You don’t think of it when your heart is beating so fast against your boned bridal corset that you have to grab hold of your father’s arm so that you don’t faint. You don’t imagine it will happen to you. You don’t believe that one day, you will be digitally altering your wedding photographs so that you can sell your mermaid-style gown and long-sleeved lace bolero to a stranger on eBay.

And yet this is where I found myself.

You don’t think about divorce when you’re walking down the aisle. You don’t imagine it will happen to you.

The divorce catapulted me into a different sort of life from the one I had imagined. Here I was, in my late thirties, single, without children, and navigating uncharted waters. Despite never having thought of myself as a particularly unconventional person, it struck me I was living an unconventional life.

My failure to have children at the time when all my contemporaries were having babies and talking about Montessori nurseries made me reassess what I could get from the life I already had. If motherhood wasn’t going to be part of the future I had always imagined for myself, where else would I find fulfilment?

Life crises have a way of doing that: they strip you of your old certainties and throw you into chaos. The only way to survive is to surrender to the process. When you emerge, blinking, into the light, you have to rebuild what you thought you knew about yourself.

It dawned on me that I had my work. I was lucky in the sense that being a writer means you never feel fully alone – you always have the company of the characters you create.

I also had my friends and family, from whom I got a great deal of love and compassion. And, actually, if I looked at the failure in a different way, it could also double up as an opportunity: I was free of responsibility. I was no longer living my life in a misguided attempt to please other people.

In October 2017, 39 and single, I found myself in Los Angeles, a city I return to again and again to recharge and write. It was there that I first had the idea for the How To Fail With Elizabeth Day podcast. I began to think about what it would be like to do a series of interviews with people about what they had learned from things going wrong.

If I examined my life, I knew that the lessons bequeathed by episodes of failure were ineffably more profound than anything I had gleaned from its slippery shadow-twin, success. What if other people felt the same way but were too afraid to talk openly about it for fear of humiliation?

We live in an age of curated perfection. On Instagram, our daily posts are filtered and framed to shape the impression we want to give. We are assailed by a constant stream of celebrities sharing their bikini-body selfies, of self-styled clean-eating gurus telling us which quinoa grain to eat, of politicians posting pictures of all the great things they’re doing in their constituencies, and it can feel overwhelming. In this bubble of smiling, happy people, littered with laughing face emojis and showering heart gifs, there is scant space for meaningful reflection.

We live in an age of curated perfection. We are assailed by a constant stream of celebrities sharing their bikini-body selfies.

That is changing: nowadays on social media, it is easier to find those admirable people who are endeavouring to be open about their struggles with everything from body image to mental health. But sometimes that can feel just as manipulated as the rest of it, as if honesty has become simply another hashtag.

And then there are the opinions. Endless, noisy opinions, generated at the click of a Tweet button. As a journalist I can personally testify to the amount of aggressively opinionated internet bile that exists out there. During my eight years as a feature writer at the Observer, I was accused of everything from having sand in my vagina to not understanding the difference between misogyny and misandry.

If I ever got something even slightly wrong – because I am human and occasionally, writing to deadline, an error might slip in that was not spot- ted by sub-editors – there would be a baying rush towards instant condemnation. Of course I should have got my facts right, every journalist should – but the outcry felt disproportionate to the offence.

In this climate, it becomes increasingly difficult to try new things or take risks for fear of immediate public opprobrium. A good friend of mine, Jim, was a civil rights lawyer in America in the 1960s, when he took on cases that he had no hope of winning because it was morally the right thing to do. Lately, he has been dispirited to see that the newly qualified lawyers he mentors are too scared to fight cases that are not guaranteed a successful verdict.

‘And I say to them: take a shot, at least! You’ve got to fail to figure out what to do right,’ Jim said to me one evening over dinner. ‘Who cares what other people think?”

But Jim’s students have grown up in an era where failure is viewed as the end point, not a necessary staging post on a journey towards greater success, and in a culture where everyone is entitled and encouraged to form knee-jerk hot takes and offer multi-platform critiques. At just the point when success has become the all-consuming aspiration, shame is now a public condition. No wonder these students felt hamstrung. No wonder we want to shy away from admitting to our mistakes or our wrong decisions.

And yet the more I thought about it, the more I wanted to pay tribute to my failures for making me who I am. Although going through negative experiences is never pleasant, I’m grateful for it because in retrospect, I can see that I have made different, better decisions because of them. I can see that I have become stronger.

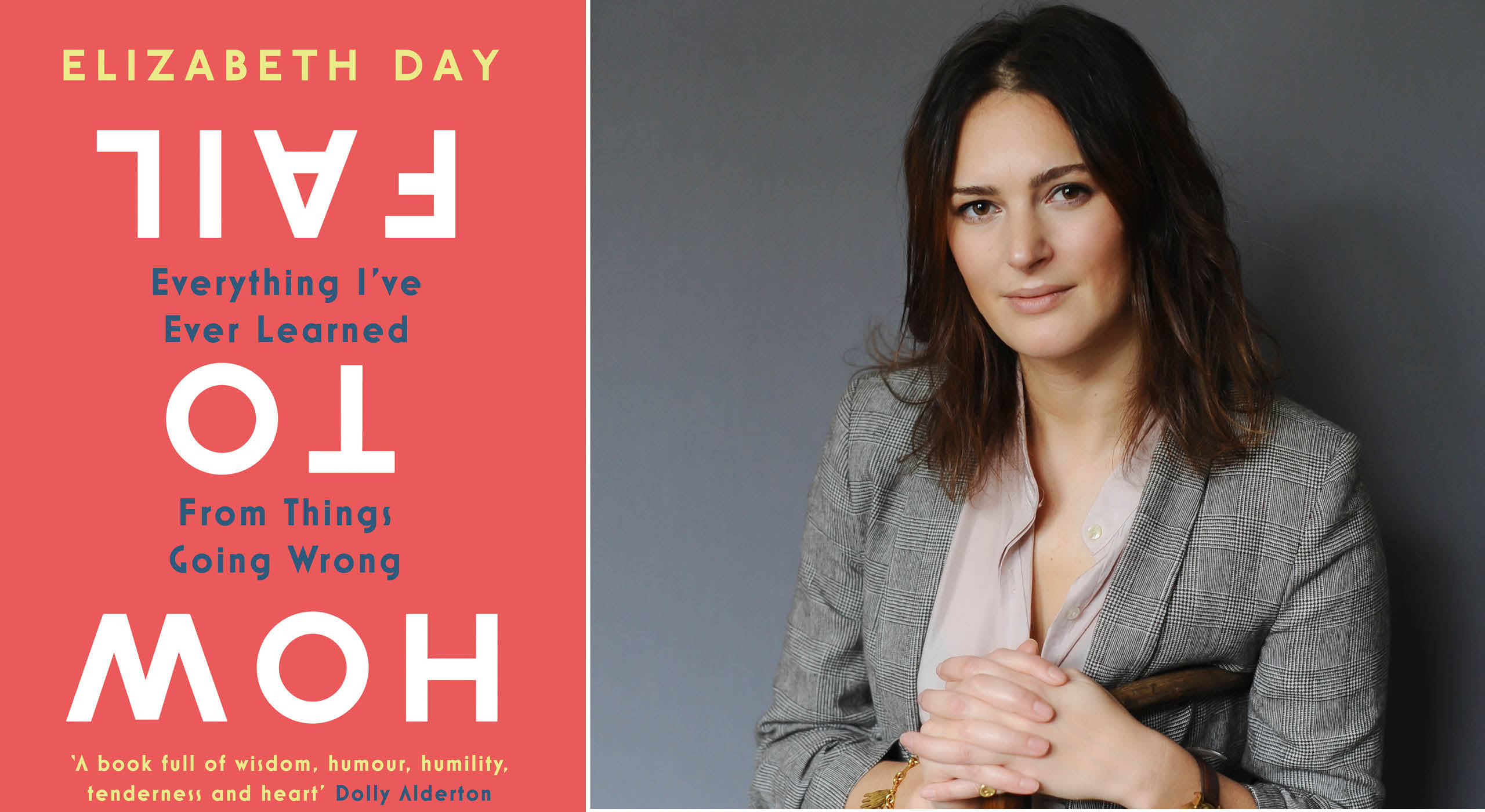

That was the genesis of How To Fail With Elizabeth Day, a podcast where I asked ‘successful’ people about what they’d learned from failure. The premise was simple: I would ask each interviewee to provide me with three instances where they believed they had failed. They could choose anything from bad dates and failed driving tests to job losses and divorce.

When the first episode of the podcast went live, it attracted thousands of listeners overnight. By the end of eight episodes, I had somehow accumulated 200,000 downloads and a book deal.

The podcast is, without doubt, the single most successful thing I have ever done. I’m aware of the irony. Other people were too. One of my friends started prefacing each text to me with ‘Noted failure, Elizabeth Day’.

I’ve learned a lot from doing the podcast, and from writing this book. One of the things that I found particularly interesting when I started approaching potential guests was how differently men and women viewed failure. All of the women immediately connected with the idea and all of them – bar one – claimed they had so many failures to choose from, they weren’t sure how to whittle it down to the requisite three.

‘Yes, I am very good at failing because I think I take risks and I push myself to try new things,’ said the political campaigner Gina Miller. ‘And when you do that, you open yourself up to failure, but it’s a way of really living life … In life we’re all going to fail, and my view is you’ve just got to get used to it. It’s going to happen, so you might as well have a strategy for how you deal with failure, and then once you’ve got that in your back pocket, you can go out in life and really take risks.’

Most of the men (but by no means all) would respond saying they weren’t sure they had failed and maybe they weren’t quite the right guest for this particular podcast.

There’s science behind this: the amygdalae, the brain’s primitive fear centres which help to process emotional memory and respond to stressful situations, have been shown to be activated more easily in reaction to negative emotional stimuli in women than in men. As a result, this suggests that women are more likely than men to form strong emotional memories of negative events or to ruminate more over things that have gone wrong in the past. The anterior cingulate cortex, the part of the brain that helps us recognise errors and weigh options, is also larger in women.

The knock-on effect of this, according to Katty Kay and Claire Shipman in their book The Confidence Code, is that women routinely fall victim to their own self-doubt: ‘Compared with men, women don’t consider themselves as ready for promotions; they predict they’ll do worse on tests, and they generally underestimate their abilities.’

If women felt more able to own their failures, I suspect this would change. I certainly had my own mind blown when the author Sebastian Faulks told me that failure was all a matter of perception. Before our podcast interview, he sent me a playful email outlining his failures as:

‘… the time my friend Simon and I lost the final of the over-40s doubles and had to be content with the runner-up glassware.

‘At cricket, I remember once getting out when I had made 98 and chipped a return catch to the bowler …

He was joking, of course, and when I did interview him for the podcast he spoke eloquently about his periods of depression and feeling as if he didn’t fit in at school. The point he had been trying to make was a serious one, however: it was that failure was all a matter of how you looked at it.

The author James Frey had a similar take, despite the fact that he was publicly outed for fabricating parts of his 2003 debut, A Million Little Pieces. ‘I don’t look at things that other people might consider failures as failures, it’s just a process, right?’ he said.

To this day, Frey said, his mantra is: ‘Fail fast. Fail often.’ It’s a mantra that holds great weight in the (male-dominated) entrepreneurial world too, where risks have to be taken in order to think differently. In this sphere, failure is not only accepted but sometimes even celebrated. There are certain venture capitalists who won’t even think of parting with their cash unless an entrepreneur has failed with a start-up company at least once – the idea being that the entrepreneur will have learned from that failure, will have got all the mistakes out of their system, and will therefore present a sounder investment.

Thomas Edison, after all, went through thousands of prototypes before perfecting his light bulb. Bill Gates’ first company was a failure. Over his career in major-league baseball, Babe Ruth set a new record for striking out 1,330 times but also set the record for home runs, hitting 714.

When asked about his batting technique, Babe Ruth replied: ‘I swing as hard as I can … I swing big, with everything I’ve got. I hit big or I miss big. I like to live as big as I can.’

What Babe Ruth was essentially saying was this: that in order to succeed on a grand scale, you have to be willing to fail on an equally grand scale too. Often the former relies on the latter, which is why failure can be integral to success, not just on the baseball field, but in life too.

What does it mean to fail? I think all it means is that we’re living life to its fullest. We’re experiencing it in several dimensions, rather than simply contenting ourselves with the flatness of a single, consistent emotion.

We are living in technicolour, not black and white. We are learning as we go.

And for all the challenges that come our way, I can’t help but continue to think: it really is an incredible ride.

This is an edited extract from How To Fail by Elizabeth Day (Harper Collins). (You should buy it – we loved it)

No Comments