I’ve never really understood that fertility is inclined to sneak away unexpectedly. After splitting up with someone at thirty it didn’t cross my mind to start dating swiftly because of fertility: none of my friends had children, so perhaps that made it feel distant. It was something I knew I wanted, but there didn’t seem to be any rush.

Within a couple of years, I was surrounded by friends with their babies, and I started noticing headlines about threats to sperm, from laptops, hormones in rivers, even cycling, and fertility ‘dropping off a cliff after the age of thirty-five’. Cruel timing: I was ready to have children, I had been for years, but I was no closer to being in love.

By thirty-seven, the notion of having children had become an ache that was beginning to dominate my thoughts. I felt that I had so much love to give, and I yearned to watch a child of my own grow and explore the world.

I went away in January to escape the city and to practise falling off surfboards in Sri Lanka. I tried to lose myself in the routine of taking a board into the tropical sea, but even in paradise, things were fairly nice rather than blissful. And while fairly nice isn’t a bad place to be, and life isn’t always going to sparkle, I felt that something important was missing.

Even in paradise, things were fairly nice rather than blissful. And while fairly nice isn’t a bad place to be I felt that something important was missing.

I spent my fortnight in Sri Lanka reflecting on my life, and, over the course of the holiday, I decided that it was time to take action.

Becoming a solo parent is not my fairy-tale wish. I don’t doubt that the ideal way for a child to grow up is with two loving parents. But when I consider it, it doesn’t feel like a choice for me. To not even try feels unimaginable, like I’d be sitting on the sidelines watching chances pass me by.

When I arrive home, I book an appointment at a clinic to get an opinion on my fertility and the options available to me.

I want to try IVF straight away, which involves harvesting eggs, rather than the less intrusive IUI (artificial insemination) which involves a few scans to check your most fertile time of the month, one hormone injection to trigger ovulation and a pipette of sperm inserted into your vagina. It’s one step up from a turkey baster.

‘A few months isn’t going to make a difference,’ the consultant reassures me. ‘I would recommend you give it two or three rounds of IUI, and then move straight onto IVF.’

I have been open with close friends and my family about hoping to become pregnant, and I am overwhelmed by the love I feel from those who have told me that they think I’d make a good parent.

Some of the most supportive words come from my mum. ‘You do know that I’ll love you just as much if you don’t have children?’ she says. I cry. I know what an important role being a grandparent is to her. I think I feel that I’ve somehow let her down, or am lesser, by not having had children of my own. I really appreciate her relieving me from the pressures that I have inflicted upon myself.

If life were a film, a convenient male best friend would emerge at this point with an offer of sperm and support. In my reality, I look into sperm donation and artificial insemination.

The clinic gives me the name of a US sperm bank they recommend. The closest thing the sperm bank resembles is a dating website, only with no flirting and a lot more baby pictures. Each donor offers a selection of photos of themselves, including as a baby and as an adult. They share information about why they have chosen to become a donor, and provide a little essay about their outlook on life.

I duly place my order for three vials of sperm – enough for two rounds of insemination (with a vial spare in case one isn’t up to standard, which the clinic recommends doing).

I have counselling sessions, both through the clinic and independently, which confirm to me how important it is to be open with any child about how loved they are, and how they are so wanted that I picked a donor to help me bring them into the world.

The closest thing the sperm bank resembles is a dating website, only with no flirting and a lot more baby pictures.

My menstrual cycle starts to be medicalised. My trips to the clinic are regular, because my ovaries are monitored every couple of days as I approach ovulation. Timing is everything: when a scan shows that my egg is ripe, I’m to give myself a hormone injection to trigger ovulation. The sperm is taken off ice and inseminated.

I am nervous and can’t relax; I feel like my insides are being grazed as a doctor puts a catheter inside me. Then, after all the poking and prodding (have I mentioned already that sex is a million times nicer?) I have to wait a fortnight to see if I am pregnant. A very long fortnight.

An early test is negative and the next month follows the same pattern: scans, trigger injection, insemination the next day. I feel unattractive and hormonal.

Then I take another test. The faintest line, barely positive, it could almost be my imagination. A week later, and dozens more pregnancy tests, I realise I really, truly am pregnant. I cry with delight. I cry with hormones. I cry with relief.

I feel lucky simply for getting pregnant so swiftly.

I become more tired. The tiny baby growing inside me is depleting all my energy, and I could happily sleep at any point. I feel as if I am peeling myself out of bed in the morning after a heavy night, with a blurry head and dry mouth.

In the few moments where I feel fully awake, I worry that I am selfish. I’ve chosen to make a baby who will have one grandparent, while I still have two. It will have no father, and no grandfathers. Luckily, my brother and two nephews will be great role models, and I vow to myself that I’ll make sure that my male friends are very involved in this baby’s life.

Although my editor at work knows I am pregnant, most other people in the office don’t. One Sunday, I am in the office when I make a throwaway comment about being pregnant, almost everyone in the office comes to congratulate me. A couple of weeks later, I mention something about being single to one of my colleagues. ‘I had no idea,’ he tells me. ‘I presumed you had a partner.’ It’s the logical assumption; when I see people with a pregnancy bump I too imagine a partner in the background, even though I’m going solo.

“I had no idea,” a colleague tells me. “I presumed you had a partner”

The heavy tiredness that I’ve felt over the past few months shows no sign of diminishing. I still feel completely wiped out. Hormones make me upset and tearful at unpredictable times. At times, I wish for a partner to reassure me (however untrue) that I am looking beautiful, rather than fat.

But for every time I feel a yearning for someone to cuddle me or help me, I’m told by someone that they admire what I’m doing. I feel buoyed up by the encouragement of people around me, and so appreciate their comments.

One friend tells me expressly that she wishes she’d had her baby alone with a donor. ‘It would have been so much easier,’ she says. ‘You don’t realise how differently you want to bring up your children until you’re doing it. And you have to compromise.”

Another friend, whose marriage is choppy, says similar, but with more sadness.

One friend tells me expressly that she wishes she’d had her baby alone with a donor.

My sister-in-law, Jess, volunteers to be at the labour, and I’m relieved to take her up on the offer. Jess has had two children herself, and after an emergency scramble the first time she is a cheerleader for C-sections. But she’s prepared to humour me as I write out my birth plan including a water birth, with hypnobirthing and lavender oil to keep me calm.

‘This sounds more like a spa trip than a birth,’ she says.

I finally meet my daughter while lying on an operating table. My plans for a water birth had – like so many birth plans – gone awry. Inside the operating theatre, an impressive team work together to get my daughter to meet me safely.

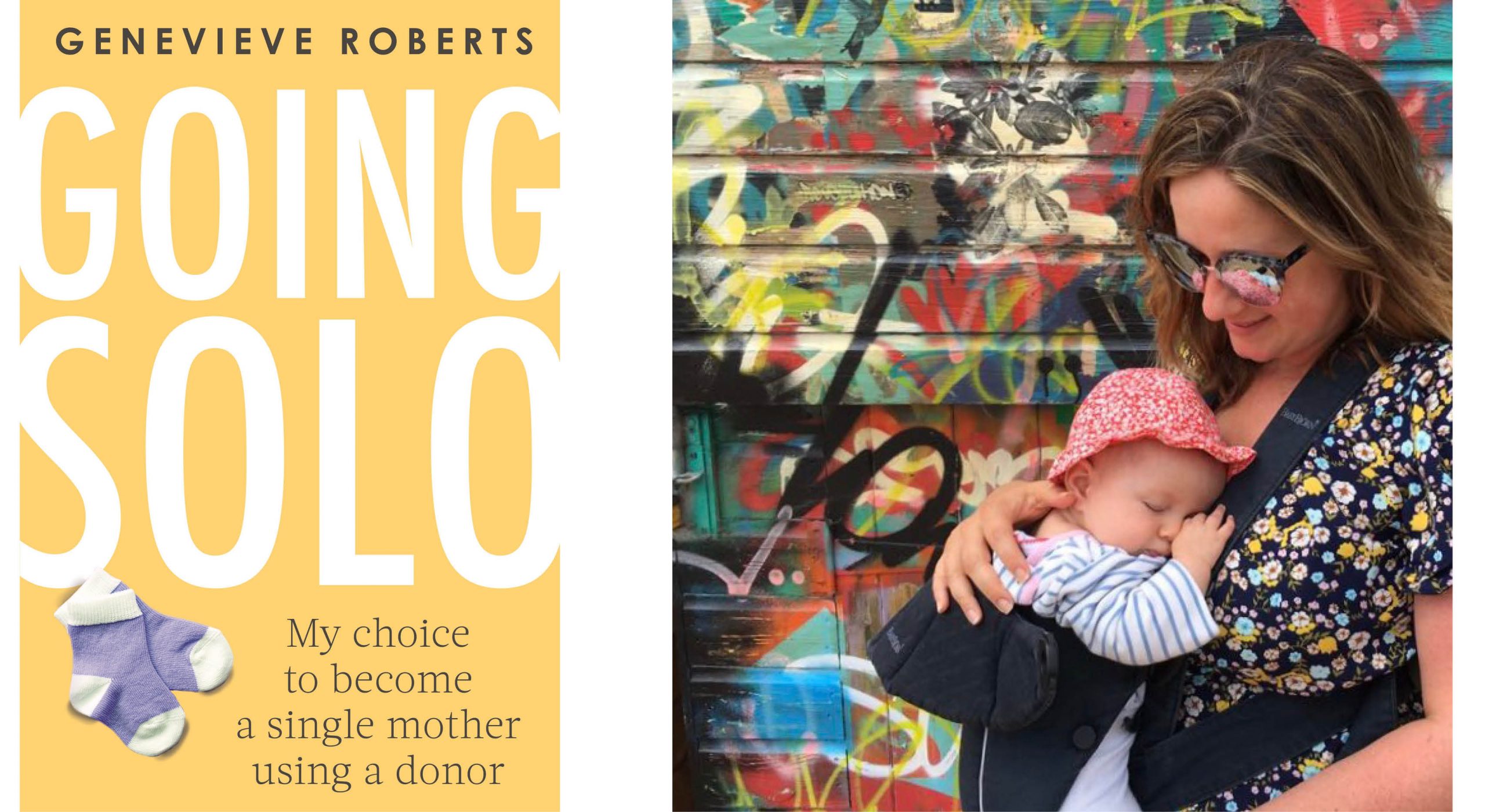

When my she’s laid upon me. I cry with joy. And while I’d been warned that it might not happen, I immediately feel a huge burst of love for my daughter. I name her Astrid Freya.

When I’m finally discharged, my brother Henry and Jess come to collect me to drive me home to my flat. Once there, I feel a sense of shock. How am I going to look after my daughter on my own? She is the most precious, important thing in my world and I want to do the best by her.

My brother and Jess leave, and I settle in for cuddles, feeling as if Astrid and I are absolutely alone in this world. An hour later, my mum arrives with a suitcase to help look after us for a couple of days so that I can learn how to be a mum.

A combination of love and hormones help me float through the first, sleep-deprived weeks of motherhood. It’s magical. I expect to feel the baby blues; the drop in pregnancy hormones that leaves many women emotional a few days after giving birth, but I’m too elated.

I don’t doubt that, for people in happy relationships, working out how to look after a child in those first few weeks of parenthood is one of the most wonderful experiences, and it helps to cement them as a team.

Not all relationships are like that, however. And there’s something beautifully simple about developing a new relationship with my daughter. I don’t need to stay up late to find out how my partner’s day has been, so if I’m exhausted, I’ll just go to bed. I don’t feel any self-imposed pressure to look attractive, so that a partner will want sex with me in the future. And there are no complications from two people having different views as to how to look after a baby – or even to compromise over names.

How am I going to look after my daughter on my own? She is the most precious thing in my world.

Late at night though, the responsibility of motherhood makes me worry about dying. Who will look after Astrid if I’m not around? I find myself wishing I had a partner, mainly because it doubles Astrid’s chances of having an alive parent until adulthood.

Gradually, though, the panic about keeping both of us alive wanes; I stop less frequently while walking the pavements of south-east London to put a hand on Astrid’s chest to check that she’s still breathing. At night, I still look over at her in the little cot that is tied to my bed, but more in wonder and delight at this perfect, beautiful girl who is my family, than in panic that she might not be doing well.

I love the stream of visitors who come to welcome Astrid to the world, and I get to see which of my parent friends enjoyed the first weeks of having a new baby by their attitudes towards me when they arrive. Those whose faces look concerned, and who ask me how I’m coping and tell me it’s all going to get a lot better, are usually scarred from tough times when they were looking after a tiny baby. Those who are excited tend to think back fondly on hours where cuddling is the only important thing.

There is one couple who visit with their son, who is a few weeks older than Astrid. Their battle scars are still fresh. They ask me how I’m getting on, and tell me how tough they’ve found various moments with a baby.

‘I find it easier having her than not,’ I say and see my friend look utterly baffled. I don’t get a chance to explain that I found things tough when I wanted a baby so a bit of sleep deprivation is nothing compared to that.

For the first few months, I feel that Astrid and I are completely tied together. I don’t want any separation between us: I find it distressing to spend time away from Astrid. We spend hours and hours gazing at each other, as I tell her what a wonderful baby she is.

I wonder how this would feel different if I’d been in any of my past relationships. I suspect that I’d have felt pulled in multiple directions. By having no partner to neglect, I’m able to suspend my responsibilities to the rest of the world and focus solely on my daughter.

My flat is a tip, the pile of unopened post now looks so ominous that I don’t want to tackle it, but nothing can make me stressed: love and breastfeeding hormones are a wonderful mix.

I do often wish for an extra hand so that I can fix Astrid’s car seat or haul in shopping along with my daughter. But I don’t think the lack of help is unique to solo mums. I learn that many women in couples across the country are bringing up their children alone during the week too, but invisibly.

I once said to a friend, ‘But there’s no one for me to pass Astrid to when I want to get out of the bath.’

‘There was never anyone for me to pass mine to either – my husband’s at work at bathtime – I put them down on the floor, or into a rocker, and then got out of the bath myself,’ she explains.

I don’t think the lack of help is unique to solo mums. Many women across the country are bringing up their children alone during the week too.

I sometimes feel a little embarrassed by how much I love motherhood. I feel that many women feel inclined to focus on the downsides, to understandably mourn an independent life that is lost to the needs of little ones. Or, at the very least, like the Vagina Monologues, to talk about how boring the first year of being a parent is.

That’s not how I feel. I love being a mum in a deeply unfashionable way. From the cuddles with a wholly dependent baby to watching my daughter start to discover the world, I don’t find it unfulfilling – completely the opposite. It makes my heart sing.

There is never a moment when I question my decision to have Astrid, but there are some days that are really hard: when Astrid is unwell and won’t sleep and won’t stop crying, and I just want her temperature to go down and for her to feel more comfortable. During those times I remind myself that even if I had a partner, they might be out or working late or away.

I start feeling curious about the donor. I have so many details about him that I know that if I were to put them into Google I would be able to find his identity speedily: I have his photo and know his profession, it would be very easy to complete the jigsaw.

I realise that, for possibly the first time in my life, I’m going to ignore my curiosity. This is Astrid’s story as well as my own, it’s our family story and we share it – but it’s her choice whether she wants to get in touch with her donor when she is eighteen. I’ll support her, whatever she chooses.

Post-script: Genevieve is now nine months pregnant with her second baby, who was also conceived through donor sperm. Astrid is now two.

This is an edited extract from Going Solo: My choice to become a single mother using a donor by Genevieve Roberts (Hachette Australia)

No Comments