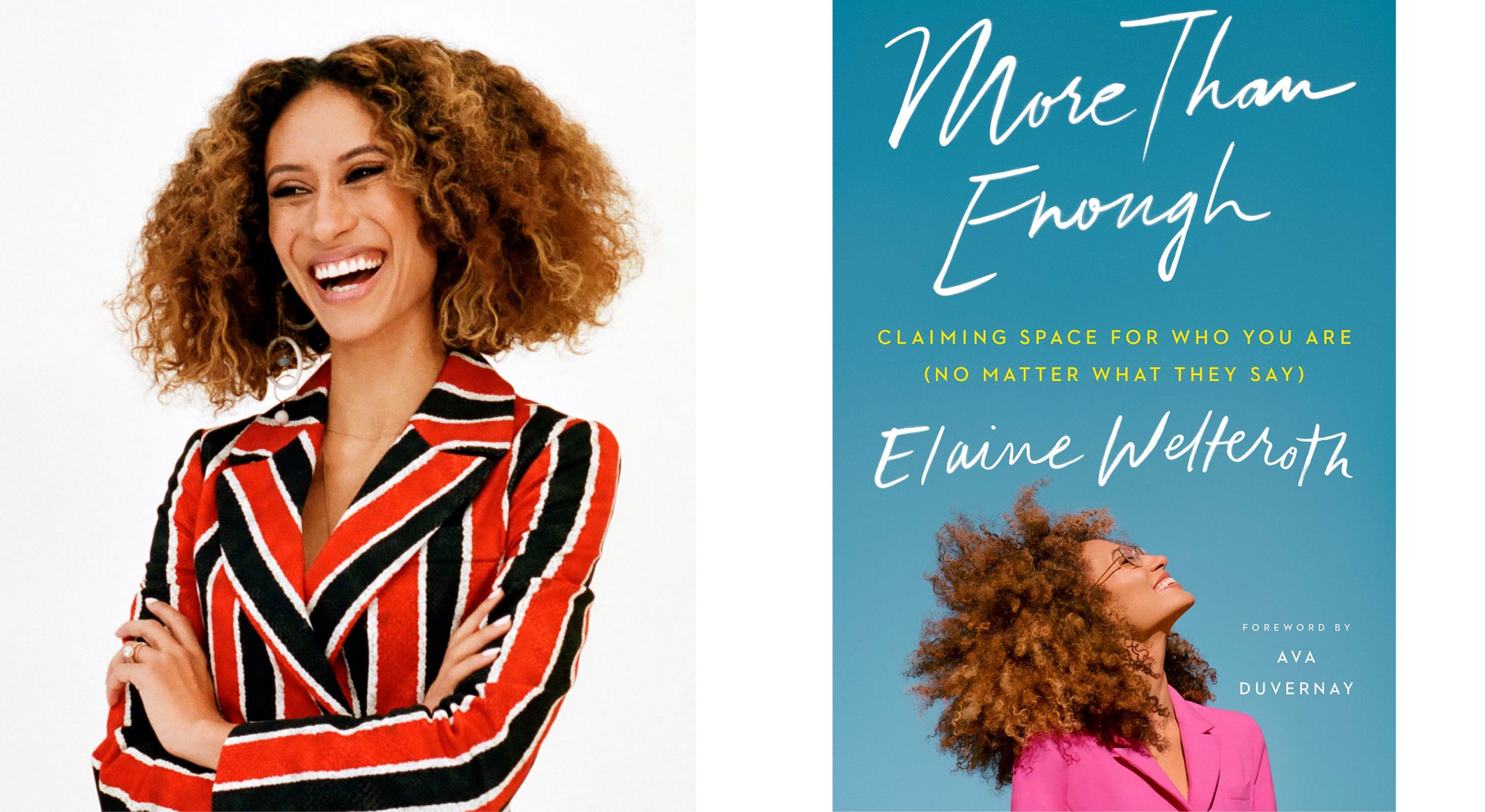

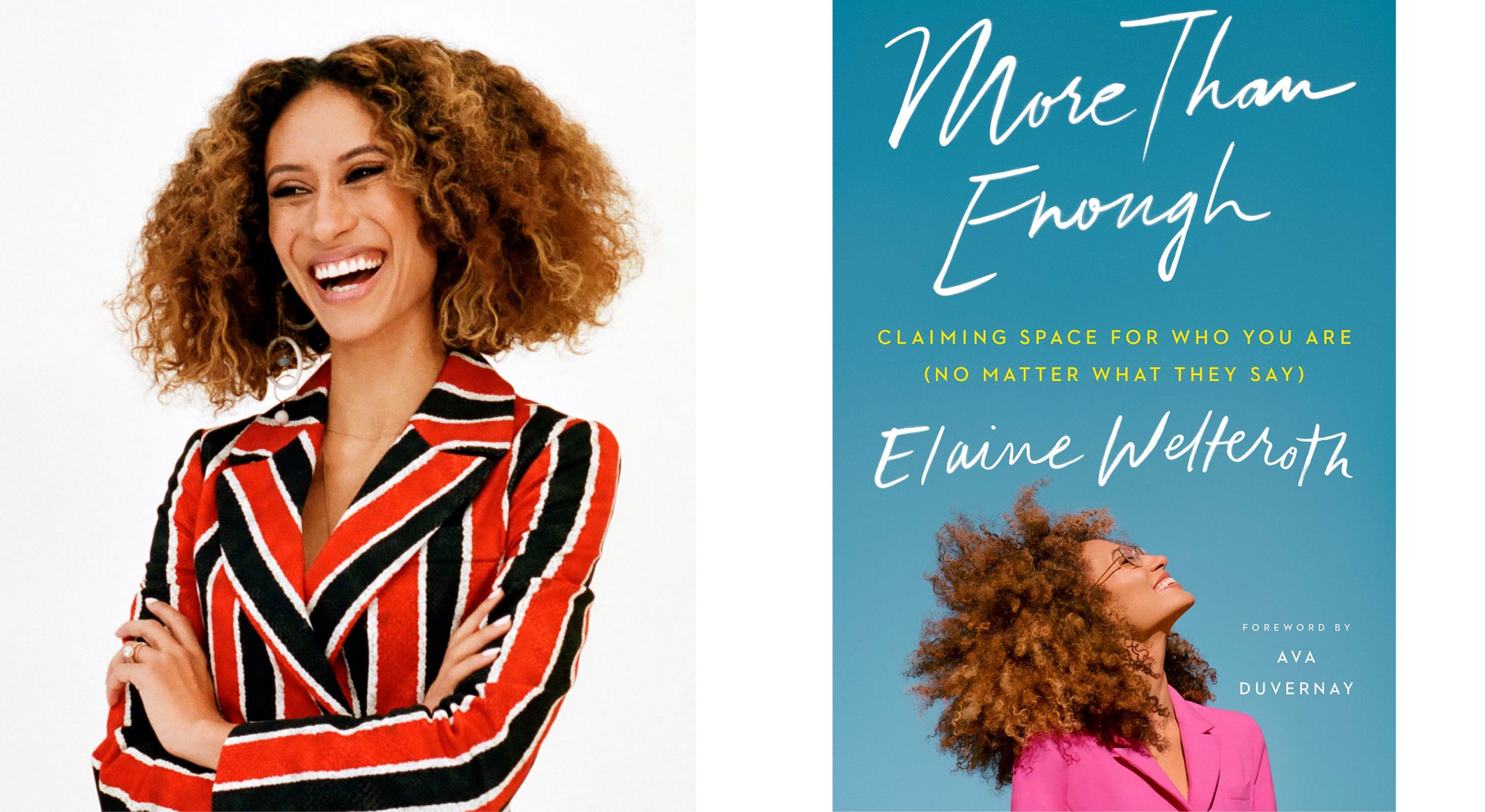

Even in a world that sparkled with exceptional talent, Elaine Welteroth burned brightly. Glamorous and smart, with a mass of curls and high-wattage smile, she rose quickly through the ranks of New York media to become editor-in-chief of Teen Vogue in 2015.

At 29, she was the youngest-ever editor of the title and only the second African-American to hold such high-profile position at the fabled publisher, Conde Nast.

Almost immediately, Teen Vogue won acclaim for its newly incisive reporting of politics and race, but it wasn’t until Welteroth’s team published an opinion piece claiming Donald Trump was “gaslighting” America that she really lit a fire. The story went viral and Welteroth was hailed as the voice of a new, ‘woke’ generation. If that may have seemed like a lot of pressure, then on the surface Welteroth seemed like exactly the woman to handle it.

Except, as she explains in a new memoir, More Than Enough (Penguin Random House), she couldn’t. By late 2017, she was rail-thin, tightly wound and had lost all sense of perspective. “I was too busy to sleep, too frazzled to eat, and, TMI, I had developed a bizarre condition where I felt the urge to pee – all the time,” she recalls in a chapter aptly titled “Burn Out”.

“There was too much coming at me. Too many people, decisions and tasks demanding my attention.” After losing four kilograms in a matter of weeks, Welteroth found herself breaking down during a doctors’ appointment, and, when Teen Vogue’s print edition was closed soon afterwards, she resigned.

Welteroth is not the first, or even the most famous, woman to have battled burnout (Arianna Huffington and Beyonce have both spoken about it publicly) but her memoir, which laid bare her struggles for the first time, was released last month – just as the World Health Organisation (WHO) officially classified “burn out” as an occupational syndrome.

While WHO stopped short of defining burnout as a medical condition, Professor Gordon Parker of The Black Dog Institute believes it’s only a matter of time. “[In the past] burnout has been a loose, nebulous concept…but it’s really on the verge of being recognised as a formal condition.”

In the past burnout has been a loose, nebulous concept… but it’s really on the verge of being recognised as a formal condition.

Because there’s no official definition, it’s difficult to know how common burnout really is. Studies tend to focus on specific occupations, and rates vary dramatically between industries. So, for example, it’s thought that around one in five teachers will suffer from burnout and up to 40-70 per cent of doctors. Several studies have found that burnout is more common among women, and almost everyone agrees that it’s on the rise.

Why? Today’s always-on culture is an obvious culprit. “We’re no longer operating to a nine-to-five, five-days-a-week schedule,” says Professor Gordon, who is overseeing the first Australian study into burnout. “Most people are in contact with their phone or email system all the time. They’re basically ‘on call’ for extended periods each week. They can’t turn their brain off because they feel hooked in.”

We’re no longer operating to a nine-to-five, five-days-a-week schedule. We can’t turn our brains off.

WHO defines burnout as “chronic workplace stress” (although Professor Gordon argues that it shouldn’t be limited to the workplace, as mothers dealing with intellectually disabled children, for example, are just as likely to exhibit symptoms). Sufferers tend to be exhausted “all the time or nearly all the time”. They’re also often anxious , depressed and struggling with sleep issues, and – unlike those suffering from garden-variety stress – tend to have stopped caring about their work or even the people around them. “They’ll also often report they can’t focus on reading things – whether at work or just in general.”

These are all familiar symptoms for Tiffany Gouge, who suffered burnout four years ago and took six months off work to recover. At the time, her husband was working as a Fly-In-Fly-Out welder, and she was logging long hours working from home as a graphic designer while also caring for their eight-month-old baby.

“I also signed up for a part-time university course. I took on way too much,” she says with a wry laugh. “I would work for hours at a time, and then one day I just couldn’t physically get out of bed. I was so mentally and physically exhausted. It felt like I was just really weighed down. I spent about four days in bed. My in-laws had to come and look after my daughter.”

One day, I just couldn’t physically get out of bed. I was so mentally and physically exhausted.

A huge part of her recovery was learning how to relinquish control and set boundaries. “I was raised to work hard, and although my husband was on quite a good salary at the time and, financially, I probably didn’t have to work, I’m the kind of person who feels that I have to contribute, so I pushed myself. [After burning out] I had to learn to let go of control, that the world will function without me.”

Professor Gordon says that early findings from his research suggest there may be a personality type that’s more prone to burnout: specifically people who, like Tiffany, are “reliable and conscientious, if not workaholic”. Put these people in a workplace where they have caring responsibilities and are faced with unrelenting pressures, and burnout may well be the result.

The link between burnout and “caring” occupations may explain why women suffer from it in greater numbers than men. “You could also well argue – although it a generalisation – that women tend to be more caring,” he adds.

Other experts like Emily and Amelia Nagoski, the sisters and authors behind a new book called Burnout, believe women are more susceptible, biologically, to stress. They also lay the blame at the feet of what they call “human giver syndrome” or the desire, drilled into most women from an early age, that they must be responsive to the needs of others. In addition, they argue that women face daily stressors – such as the pressure to conform to body ideals and the frustrations that come with working in less highly paid positions – that men simply don’t deal with.

For former magazine editor Emma Vidgen, from Sydney, burnout was the result of the immense pressure to buck the industry-wide trend of declining readership, together with a Type-A mindset.

She also points to the #hustlehard mentality that many millennial women are encouraged to subscribe to, and which is plastered all over social media in the form of motivational quotes and “inspirational” memes. “I think I was a card-carrying member of that ‘work until you drop’ cult,” she says. “I used to push myself so, so hard because I believed that was what you had to do to be successful.” But she describes that #girlboss narrative, which portrays exhaustion as the inevitable price that successful must women pay to reach the top, as “so damaging, because it’s not sustainable”.

Vidgen’s experience prompted her to quit magazines and co-found the holistic website TheWaywardCo. Looking back, she says, there was another pressure at play – and that it’s one felt by many millennial women: the sense that they must achieve success in their careers before they have children. “I felt immense pressure to get to a certain place in my career before I started a family otherwise [I felt] I wouldn’t get a look in.

It took stress-induced appendicitis and a subsequent, life-threatening bout of septicaemia for public relations powerhouse Tory Archbold to realise that she was suffering from burnout in 2013. But even then, she didn’t stop working. “I was told I needed a six-month recovery period [after the appendicitis] … but I had a business with global clients and I was a single mum at that point. I used to get ready for work and I could only make it down the stairs.”

Eight weeks after the operation she finally accepted that she needed to make sweeping changes, and after downsizing her firm, she launched a new platform, Powerful Steps, which aims to empower and mentor other women. Reflecting on her brush with burnout, she says that she was always reluctant to show any vulnerability. “If I wanted to work with the big boys, I couldn’t show weakness. I grew up in a world where you didn’t take sick leave. You worked through.”

The problem with many women who suffer burnout is that they’re so conscientious, perfectionist and driven that they present a capable front to the outside world, says registered psychologist Therese Lardner of Mindset Coaching, who specialises in burnout, having suffered from it twice herself. “When you’re in that situation you blame yourself. You think: ‘Why can’t I handle this?’ And you don’t have energy to evaluate the situation properly.”

Lardner believes the key to addressing burnout is self-awareness. “We all take our personal preferences and values – our ‘derailers’ – with us to work, and that’s what gets triggered by those [toxic] workplaces.” i

When she meets clients with burnout the first thing she suggests is “simplification”. “If someone is mentally and physically exhausted the last thing they need is advice on the extra stuff they need to do – like go to the gym or meditation.”

Professor Gordon agrees that, anecdotally at least, taking an extended break can often help those with severe burnout. However, he says it may not be successful in all cases. “If you’re workaholic and you develop burnout being told to take a holiday is not going to cut the mustard.”

He believes that anti-depressants may not treat burnout, even though he suspects many sufferers are prescribed them. For some people, he adds, burnout can be difficult to shift. “The biggest long-term consequence is that people just don’t get pleasure in life. There is a significant impairment in their quality of life.”

For Elaine Welteroth, recovering from burnout meant revising lifelong perfectionist and workaholic tendencies. As a junior editor, she was once asked in an interview about her career mantra and replied, slightly tongue-in-cheek, with a quote from Crocodile Dundee’s Paul Hogan. “Bite off more than you can chew and chew it as fast as you can.”

Towards the end of her memoir, she reflects on that moment, and writes: “I wish I could go back now and revise that Crocodile Dundee career motto… Now at 32, better advice would be: “Bite off only what you can chew. Take one bite at a time. Chew thoroughly. Swallow fully. Breathe. Make room for the next bite. Find time to laugh. It’s better for digestion”….Not as pithy, I know. But…there is hustle and there is flow; and you cannot successfully achieve one without the other.”

Have you suffered from burnout? The Black Dog Institute is studying burnout, and looking for people who have experienced it to fill out this anonymous survey.

What burnout feels like…. (from women who have been there)

“I wasn’t sleeping. I would go into the toilets and cry”

Clinical psychologist Therese Lardner has experienced burnout twice

“I was working in strategic HR and leadership development coaching when the GFC (global financial crisis) hit and our clients started dropping like flies. The pressure in the organisation began to rise and rise to the point where I became really unwell.

“I was so sick I would wake up at 4am and be sick until 6am. Then I would be bone-crunchingly tired until I got home. It was rinse and repeat, day in day out. Being made redundant was the greatest gift of my life.”

“I lost interest in eating. I started calling in sick every day”

Amy O’Connor poured herself into her job – until she became unwell. Years later, she now works for a start-up, Soldier.ly that creates software for wearable devices that detects stress

“I’m a perfectionist and one of those people who takes on way too much. I had been working in a new role for 18 months when I experienced burnout. Work had taken over my life. The [company] brand had just become an extension of me. It was also a really toxic culture and really competitive.

“I started to withdraw from people. I wasn’t sleeping at all. I lost interest in eating. I saw a life coach who offered meditation. I tried epsom salts in the bath. I was trying every tactic in the book. I ended up going to the GP, and she asked me to fill out a survey [on chronic stress] and I couldn’t even pick up the pen. She told me I had chronic stress from the workplace. Until then I’d no idea what was going on and I’d blamed myself. Now I’m more wary of my own personality and [how it interacts with] my workplace.”

Years later, she now works for Soldier.ly, a start-up that develops software for wearable technology – like watches – that helps individuals to detect and manage stress in the workplace. “

“I just felt really wired and productive”

Publicist Renae Smith, who runs her own firm The Atticism, spent a year overseas to recover from burnout

“When I was busy I felt ok. I just felt really wired and productive. But when I tried to relax I just couldn’t. The weekends were the worst. I would have anxiety and I couldn’t sleep. I’d get up at 7am on a Saturday and do a deep clean [of the house] and then sit on the couch and say, ‘What shall we do today?’ I found it impossible to be doing nothing. At the time I just felt super productive, but I wasn’t much fun to be around. I did nothing socially.

I began to wake up in the morning and start sweating – a lot. I went to the doctor as I started feeling dizzy and my heart started beating really irregularly. One day they put me on an ECG and told me: this is what burnout is. You need to take a break. So I moved to France and ran the business for a year, and now that I’ve been done that path I can identify it. At my [PR company] staff can start whenever they want and finish whenever they want. We win awards all the time for the best PR employer.”

“Some days, I had to nap in the afternoon”

Alyse Cocliff, of An Apple A Day, suffered burnout after studying for her nutritional medicine degree

“I had done my four-year degree in three and a half years and then launched my business. I told myself that [the pressure] was only for a short period of time and then I’d be ok. But within four to six months I wasn’t operating at capacity. I started to really fatigue; I was irritable and I’d lose concentration. There were days when I’d have to have a sleep in the afternoon. Productivity was out the window. It’s hard to explain to someone who isn’t in it, but it’s like a fog.

Today, my own experience has enabled me to detect early warning signs in my patients. In a way I’m grateful for the experience because it’s made me a better practitioner.”

No Comments