There are people who, as you read this, are making minute-to-minute calculations about their safety, who feel that familiar anxious knot in their stomach that tells them they are not safe.

There are others who, through their distorted worldview, cannot see that it is they who are abusive, that they are the ones doing the harassing, that they have violated consent.

In fact, they often believe themselves to be the victims, and in their outrage at the way they have been disrespected, can become terrifyingly fixated on destroying the lives of their former loves, or of those who’ve had the courage to stand up to them. These people can also be almost impossible to stop.

Gendered violence is not just a niche issue. It directly impacts millions of Australians, and no amount of wealth or privilege can insulate you against it. For our public safety, for the cohesion of our communities, for our kids’ futures, we must do more than tinker at the edges. We need our political class to believe that, working together with communities, they can make gendered violence a rarity. Most importantly, they must be willing to burn some political capital to achieve it.

Big news last year. Barely mentioned now.

Last week, PRIMER illustrated how, despite gendered violence dominating political headlines for much of last year, it has barely been mentioned during this election campaign – not by major parties, nor by the media.

To put a finer point on this, Dr Kristin Ferguson did a keyword analysis on every public speaking appearance from the Prime Minister and Opposition Leader during the campaign (from transcripts on their websites). The terms ‘violence against women’, ‘consent’, ‘sexual harassment’, and ‘coercive control’ were not mentioned once by either leader. Albanese mentioned ‘women’s safety’ and ‘gender equality’ once in his publicly available remarks. Gendered violence is, in this election campaign, literally unspeakable.

A turning point

Which is weird, because this is actually a pivotal moment for gendered violence in Australia. On July 1, the first National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and Children – which has been in place since 2010 – will expire.

In its place will come a new plan – one that’s only been released in draft form. That draft included an encouraging set of principles – a new focus on recovery from trauma for example, and a specific response for victims who are LGBTQI – but no specific action plan to show how this will be pursued. Which programs will be funded to do this? How would success be measured? Instead of a detailed action plan, this draft more closely resembled a pamphlet.

This has alarmed close observers, especially because the previous national plan – despite its positive achievements, like establishing the primary prevention agency Our Watch, the federal research body ANROWS, and the national crisis helpline 1800 RESPECT – failed in its primary objective: to reduce violence against women and children.

In fact, unlike virtually every other public health plan (like the one to reduce smoking), the national plan to reduce violence did not include any actual reduction targets. Instead of working towards tangible reduction targets, like a significant reduction to domestic homicide, there were a set of utopian outcomes, like ‘communities are safe and free from violence’ and ‘relationships are respectful’. These outcomes were to be delivered by 2022.

Will this new plan – which will determine our national approach until 2032 – include targets? Will it outline a credible action plan to meet them? How will success be measured?

What gendered violence advocates want

Insiders say a revised draft plan, circulated privately, does include targets, but they are still confidential. Annabelle Daniel, chair of DV NSW and CEO of Women’s Community Shelters, says the targets need to be clear, and ambitious.

“We want to see an 80 to 90 per cent reduction in domestic and family violence homicides across Australia (in the next decade),” says Daniel. “We want to see close to 100 per cent of kids across primary or high school being taken through age-appropriate respectful relationships education.

“And we want upwards of 95 per cent of women who’ve experienced domestic and family violence to say that the systems that supported them during and after provided them with the help that they needed to get on with a new life.”

How much the Greens, the Liberals and Labor will commit

The other outstanding issue is just how the National Plan will be funded. The sector’s funding requirement has been the same for years: to properly fund the national plan, the federal government must allocate $1 billion per year.

The only party willing to meet that is the Greens, which is advocating for $12 billion over 12 years. “That’s the amount we need to meet the existing demand, and for there to be enough wriggle room system for any future demand,” says the Greens spokesperson on women, Senator Larissa Waters.

Demand for services has escalated: over 90 per cent of services say demand has increased since Covid.

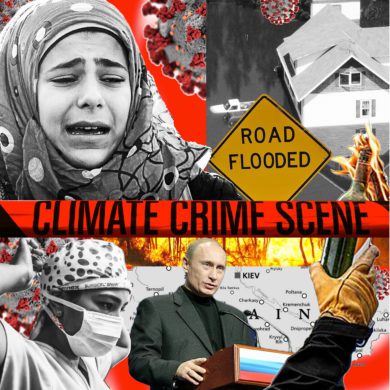

Times of crisis virtually always instigate a spike in domestic and sexual violence. We’ve just experienced two years of rolling climate disasters – droughts, bushfires, floods – and the scientific modelling that predicted those disasters tells us we should expect this time of rolling crisis to be the new normal – and if anything, to become only more frequent and severe as the world warms.

Protecting human life during these crises will require more than firefighters and local residents in dinghies – we’ll also need a securely funded domestic and sexual violence sector to deal with the inevitable fallout.

Protecting human life during these crises will require more than firefighters and local residents in dinghies.

In this year’s budget, the Coalition promised more than $2.2 billion over six years for women’s safety, health and economic security (of which $1.3 billion is earmarked for women’s safety). CEO of Full Stop Australia Hayley Foster has been campaigning for the $1 billion amount since 2019, back when the Coalition government was only willing to commit $109 million a year ($328 million over three years). The funding increase, over such a short period, is “very positive”, she says.

Labor has committed to match the Coalition’s funding commitment but won’t say whether they will increase it. One advocate, speaking on background, said that in meetings during the campaign, Labor showed no interest in increasing this funding, and in fact were pushing back on what the sector was asking for.

‘That’s why I don’t think this has been a big election issue. Labor would be capitalising on it if they wanted to invest more.”

However, in comments to PRIMER, Labor’s shadow assistant minister for the prevention of family violence, Senator Jenny McAllister indicated otherwise: “My biggest criticism of the government’s draft national plan is that its ambitions for change are not clearly reflected in their budget priorities.” There was no specific information, however, on whether Labor would commit more to the Plan.

If a billion dollars a year in gendered violence response and prevention sounds like a lot, consider what domestic violence alone actually costs the Australian economy: $26 billion per year. “So actually,” says Daniel, “a billion dollars a year looks pretty cheap.”

Actually a billion dollars a year looks pretty cheap.

Whoever ends up in Kirribilli on May 22 will have just six weeks to finalise the national plan before the previous one expires on July 1.

The sexual harassment laws hanging in the balance…

The other nation-changing reform that hangs in the balance is the 55 recommendations in the Respect@Work report, delivered by trailblazing Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Kate Jenkins.

If all 55 are adopted, this reform package could revolutionise the way we handle workplace discrimination and harassment – most notably, through the new ‘positive duty’ on employers to prevent sexual harassment from happening in the first place.

This would make employers legally obligated to take reasonable steps to prevent sexual harassment, just like they have an obligation to do all they can to prevent workplace injury.

It might sound dry and bureaucratic, but the power of this cannot be underestimated: it could finally shift the burden away from victims and on to employers.

…And where the parties stand

On the issue of keeping everybody safe in the workplace, there is a clear choice: Labor and the Greens will endorse all 55 recommendations, whereas the Coalition has committed to only 42 (work is apparently ‘underway’ on the remaining recommendations).

Among several unticked reforms, the Coalition refuse to endorse Respect@Work’s central recommendation: the positive duty to prevent sexual harassment.

It also voted against amendments to expressly prohibit sexual harassment in the Fair Work system (a change that Labor and the Greens support).

Labor has promised $24 million to fund Women’s Working (WW) centres, which advise and represent victims of sexual harassment, in every state and territory – another key recommendation in Jenkins’ report.

The hot issue of affordable housing

From the women’s safety sector, one demand outstrips all others. “What I keep my eyes over is not just the DV funding commitments, but the housing ones as well, because they’re so interrelated,” says Daniel.

Daniel is no outlier – when the National Women’s Safety Alliance surveyed the domestic violence sector on what they needed from government, affordable housing was their top priority.

“What the peak bodies are advocating for is 50,000 homes a year for the next decade,” says Daniel. “We need to address the backlog, because 75 percent of women’s homelessness is caused by domestic and family violence. And if we’re saying ‘why doesn’t she leave?’ Well, where can she go?” For many women, the choice is stark: stay with your perpetrator, or risk becoming homeless.

What the parties will fund

Only the Greens have proposed to meet the demands of the sector, with its proposal to build a million new public and community homes.

Labor has made housing a central election promise, committing $10 billion to create 30,000 social and affordable homes over five years, and put 4,000 of those aside for women and children fleeing domestic and family violence (as well as older women at risk of becoming homeless). A further $100 million will be allocated to crisis and transitional housing.

Both of these funding proposals are above and beyond what’s been promised by Government. Analysis from Fair Agenda shows the Coalition government funding for social housing and homelessness services that assist victims and perpetrators of family violence has decreased in real terms over the past decade.

Though there is clear daylight between the two major parties, they are still both falling short of what is needed, says Daniel. “There hasn’t been a significant enough commitment to social housing from either of the two major parties.”

There hasn’t been a significant enough commitment to social housing from either of the two major parties.

Solutions for First Nations people

There’s another issue that is front and centre in the sector’s mind, and that is what an incoming government will do to ensure self-determination for First Nations people.

Cheryl Axleby, co-chair of Change the Record, is unequivocal. “For decades, government-led, paternalistic, mainstream responses to violence in our communities have not reduced violence against us – they’ve made things worse for us, our children, families and communities. That’s why we have been calling for a self-determined, community-led response by and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and genuine commitment from government to invest in our services and communities on our terms.”

Looking at promises from both major parties, Axleby still sees resistance to deliver what First Nations communities need.

“Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women know the causes of and solutions to the challenges we face. Yet neither the Morrison Government, nor the Opposition, have committed to adequately funding our frontline family violence prevention and legal services to meet community need.

“Specialist, culturally safe First Nations family violence prevention and legal services are having to turn away women seeking safety because the Government has failed to adequately fund their services. At a bare minimum if the Government is serious about closing the gap, then our women need somewhere safe to go to get legal assistance, help finding housing and support for their families when they are fleeing violence.”

Axleby does welcome one funding commitment – $79 million for justice reinvestment – proposed by Labor and supported by the Greens. The move to establish a national justice reinvestment body would “invest in our communities, instead of just throwing money into police and prisons which so often let our women down,” says Axleby.

In outback NSW, in the small town of Bourke, justice reinvestment has achieved remarkable results: statistics from 2017 showed that in just a few years, domestic violence-related assaults were reduced by 39 per cent; by 2018, the revictimisation rate was down by a third. Critically, other measures – hospital admissions for assault, child removals – were by 2018 at historically low levels.

“Justice reinvestment is a way of governments recognising the expertise and lived experience of the community itself, and to direct money into the areas of need that women, First Nations peoples and communities identify as most requiring investment.”

“We won’t see an end violence against women until we start investing in the things that make our communities safe. That means affordable housing, adequate social security payments so women have financial independence, it means drug and alcohol programs and it means wrap around family supports.”

We won’t see an end violence against women until we start investing in the things that make our communities safe.

Ultimately though, the answers to gendered violence won’t be found in a set of election commitments. Solving this problem will require not just nous, but political courage. On this front, Labor’s spokesperson on family and domestic violence, Senator Jenny McAllister, says they are ready to deliver ‘real change’. “I feel very optimistic. In my adult life, I’ve never seen such strong, public, broad support for change for women. I feel as though we collectively have a chance to do something good. But we have to win first.”

Victim survivors of gendered violence know full well how empty promises can be. They will be waiting to see not what the next government says, but what it does.

PRIMER approached the Minister for Families and Social Services, Anne Ruston, for comment, but did not receive a response.

To read more stories like, sign up to PRIMER’s free weekly newsletter.

No Comments