I am a woman in my 30s with a home, a dog and a couple of thriving houseplants. I eat broccoli by choice, have a monthly Excel budget and, on a good day, wear matching underwear. I work hard, serve red wine from a decanter and am accumulating a wardrobe filled with smart investment pieces over silly fad buys.

I look like an adult. I sound like an adult. I am an adult.

But for me, nothing rocks these beliefs like filling out an emergency contact form. I spell out the letters of my next-of-kin – M-U-M – and suddenly I’m a child back at school, completing an excursion permission slip. I know I’m lucky to have a lovely, dependable mother who I can always call on, but at my age, shouldn’t I have a life partner to fill that box? Isn’t that part of being an adult?

My identity crisis, it would seem, is not unique. Today, Millennials and Gen Zs are experiencing adulthood’s traditional rites of passage – a house, a spouse and a baby – later in life, if at all, and this delayed development is explored in a crop of new books and studies about what it means to be a grown-up in 2022.

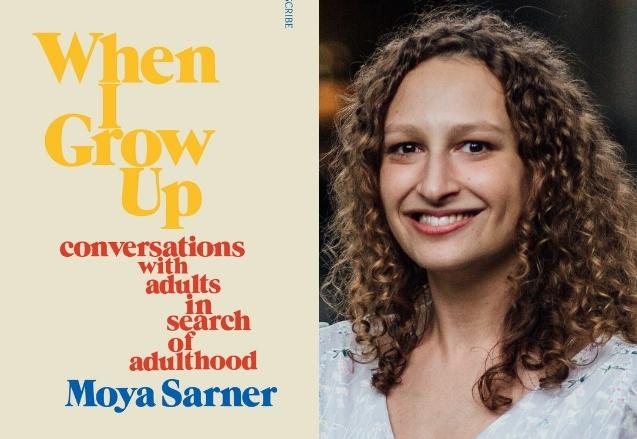

“People in Western nations seem to be growing up later and later, as the accepted social landmarks of adulthood drift – or are pulled – further from our grasp,” explains Moya Sarner, journalist, psychotherapist and author of When I Grow Up, released in Australia last week.

“Here in the UK, the average first-time home buyer has risen by seven years over the last five decades … In Australia, the proportion of women having their first child over the age of 30 has more than doubled over 25 years.”

Failure to attain these markers can leave us feeling delayed and under-developed – like we’re waiting to cross the finishing line, or have somehow missed the deadline.

But there’s a catch, because a marriage and a mortgage don’t necessarily equate to feeling like a grown-up either.

When Sarner started researching her book, she had a home, a husband, and a full set of white goods. Yet it was finding a mass of squiggly maggots in her bin that sent her into an existential spin.

“I immediately rang my mother to ask what to do – it was like I had no mind of my own,” she recalls

“I had the paperwork to prove I was the competent, confident adult I should be. But the more boxes I ticked, the more I realised how shaky, how tenuous, my own feeling of being-an-adult was … [It was as if] I had a licence that said I was a driver – but I knew that deep down, I wasn’t one.”

I relay Sarner’s case of imposter syndrome to some friends and colleagues, who vehemently relate. “I’m 34 with a mortgage, but every time I go to a strata meeting I feel like a kid dressed up in my mum’s shoes,” says one.

Shares another, “I didn’t wear a blazer until a few years ago because I thought they were too grown-up for me; I’m 41.”

For others, there’s a cruel irony in getting older. “You spend your whole childhood wanting to grow up; in the movies ‘coming of age’ is portrayed as a blissful entrée into adulthood. Yet in real life you turn 18 and suddenly become a legal grown-up, with no clue of what that entails,” admits a childhood friend. “Adulting isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.”

Note the use of “adulting” as a verb. Shortlisted for Word of the Year by the Oxford Dictionary in 2016, it’s generally used by Millennials to poke fun at their delayed development (and the drudgery of grown-up duties) with snappy memes and pastel-coloured quote tiles.

By nature, the word highlights the way many of us feel: that we’re playing adults rather than being adults.

Every time I go to a strata meeting I feel like a kid dressed up in my mum’s shoes

So what happens when these slow-to-develop Millennials and Gen-Xers become parents? I imagine, perhaps reductively, that for many women, having a baby must be the moment that magically tips them into adulthood. Over night, you move up a generation and literally become the grown-up in the room.

But it’s not that simple, says my sister, 40. “I remember being 32, pregnant with my first child, and really looking forward to becoming an adult. I thought that when I had him I’d become more fierce – suddenly able to stand up for my child and for myself – because those are qualities I seem to equate with adulthood,” she says. “But it didn’t happen, I’m still the same. It’s only really in the last few years that I’ve started to feel like a grown-up. I wonder if the pandemic changed something in me – having to be aware of risk in a more serious world.”

On that note, stress and trauma will impact individuals in disparate ways, either leaving them emotionally stuck at the age an incident occurred, or forcing them to grow up.

There can be an element of privilege, therefore, in feeling childlike. Had I, for example, been left to fend for myself as a 15-year-old, I probably wouldn’t be here mulling over the meaning of adulthood.

I wonder if the pandemic changed something in me – having to be aware of risk in a more serious world

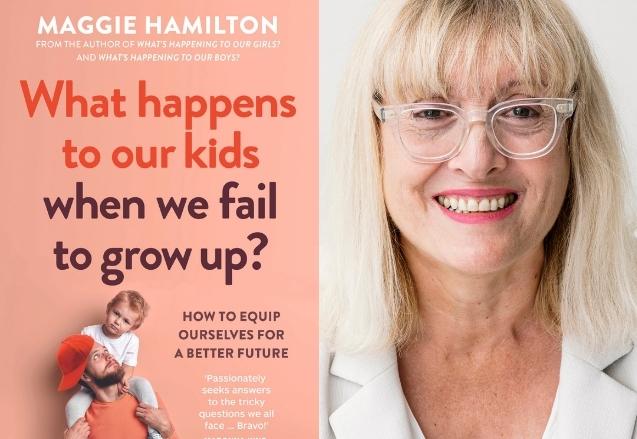

I speak to author and researcher Maggie Hamilton, who was spurred to write her latest book, What Happens To Our Kids When We Fail To Grow Up?, after observing a rise in Peter Pan syndrome.

“I was seeing really intelligent and capable people around me, from Millennials to Baby Boomers … stuck in a permanent state of adolescence,” she says. “There was frequent use of the words ‘special’, ‘deserving’ and ‘unfair’; an increase in self-focused behaviour and conversations; a rise in boredom, anxiety and depression; people laughing less, reaching out less and complaining more.”

She points to the early days of the pandemic as a snapshot of our rampant self-interest and aversion to discomfort. “The frenetic pushing and inexplicable run on toilet paper… and what about those who [spent] their days grumbling on social media and elsewhere about the restrictions?” she asks. “Never mind that countless health workers were putting their health and lives at risk.”

The good news, she continues, is that growing up is a choice we can all make. “My advice to someone wanting to grow up is to realise that we all have fears, but to dare to nudge [your] way forward rather than retreating and hiding. An adult stands on their own feet, even when things get tough,” she says. “And instead of material milestones [such as a marriage and a mortgage], we need to concentrate on qualities like kindness, wisdom and generosity.”

Sarner, too, believes we need to rethink the defining traits of adulthood. “When it goes well, growing up brings with it qualities of kindness, sensitivity, courage, and a capacity to tolerate imperfection,” she explains. “Those are the real signs of maturity for me.”

After spending 18 months immersed in her research, Sarner says she’s now found a level of acceptance in her adult identity; namely, she’s no longer trying to grow into someone she’s not.

So does she still call her mum in a crisis?

“Actually, I don’t seem to turn to her so much any more, I think I’ve grown in confidence [and am] able to find more of the answers I’m seeking in myself,” she says. “Something has definitely shifted over the last couple of years – I think to do with my analysis, with the pandemic, finishing my training [as a psychotherapist], and finishing the book. It’s not that I now feel like an adult, but I don’t feel quite so much not like an adult.

“Perhaps letting go of my fixed view of what an adult should be has allowed me to grow into a fuller version of myself. It’s still very much a work in progress, though.”

On that note, Sarner tells me about one of her interviewees, Pog, who admitted that at the ripe old age of 90, she still doesn’t identify as a grown-up.

She told Sarner, “The real sort of inside growing up, the mental attitude, I don’t feel I’m there yet. I think there’s still stuff to do – though I’m not sure what… I don’t feel that for myself, the process is complete. I think there’s still stuff there which I haven’t yet learnt.”

That’s the thing about adulthood. It’s not a destination we’ll suddenly arrive at, or a finishing line we’ll cross. I decide it’s a bit like waking up on a milestone birthday. You expect to somehow feel different, but you’re still just… you.

And when you’re truly ok with that, maybe you’re really growing up.

When I Grow Up by Moya Sarner (Scribe) and What Happens To Our Kids When We Fail To Grow Up by Maggie Hamilton (Affirm Press) are out now

Main illustration by Karen Lynch, Leaf And Petal Design

No Comments