I remember the sound my body made as it hit the ground.

A sharp crack. Then the white heat of pain that stabbed through my body, escaping through my mouth in an almighty howl.

I tried to scramble to my feet, but I couldn’t get up. As soon as I raised my shoulders, I crumpled. My pelvis was broken. That much was clear. Shattered was actually the word that kept coming to my mind.

Help.

I yanked my daypack towards me, scrabbling in the front pocket for my iPhone, my hands shaking as I dialled 911.

Call Failed.

No. No, no, no. I dialled again.

Call Failed.

A horrifying and crushing realisation hit me with the full force of its weight:

I am out of phone range here.

I wasn’t even meant to go to California. I had only just packed up my life in the UK, and stepped on board a plane to Canada. The plan, if you could call it that, was to spend a few months on the road, exploring places I’d never been, immerse myself in the great outdoors.

What I was seeking was change. Life in London had left me burnt out and bruised. My day job as a magazine sub-editor was constant high-pressure. I felt hollow, anxious, lost.

That first week or so in Canada I’d spent the days walking around Toronto, and studiously pitching feature ideas to travel magazines. Then, Natalie and Lou – a pair of former London friends – were now living in Joshua Tree, California. Did I want to come to the desert and house-sit for three weeks? Absolutely yes.

I’d arrived to the house late, in pitch dark. I had my heart set on completing as many trails as I could. And there was one in particular that I had in mind.

I felt hollow, anxious, lost.

Lou and Natalie had told me about the Lost Palms Oasis, an in-and-out hike of a little over four miles each way, leading to a large congregation of palms hidden deep in a valley. I decided to schedule it halfway through my stay, thinking that by that stage I’d be used to walking in the desert.

The night before I set off on my day hike I had gathered anything I thought I might need. I wouldn’t need much. It was a day trip. Just a few bits and pieces.

It was idyllic walking that morning; the route began with a slow, steady climb up staircases of rock, eventually flattening out to a path along a high dune, the low desert rolling out for miles on all sides. The landscape was magical.

Often, the most dangerous moves are the ones that don’t feel like it; there are no red flags, no alarm bells.

I was crossing a huge boulder, and the it was moment I gave most of my weight to the rock that I realised it wasn’t going to hold me.

Everything during those next few seconds happened so fast. My right foot slipping. The desperate flutter as the fingers of my left hand scrabbled for something to hold onto.

I was airborne for about half a second before hitting the ground, landing about 20 feet below the edge of the rock face.

Everything during those next few seconds happened so fast.

The left side of my pelvis had taken most of the impact; shattering, pieces disconnected, rendering me immobile. Behind me was the stack I had fallen from, and a couple of feet to my right was a high, overhanging boulder.

The futility of my situation hit me hard. I couldn’t move, I couldn’t call anyone. I combed my iPhone extensively, desperately, looking for any sort of app or method of communication.

I opened my maps and found I could still access my GPS in my downloaded maps. I could at least see where I was. There was the Lost Palms Oasis trail, a tiny dotted line in a vast expanse of nothing. And there was me, the little blue dot.

Except the little blue dot was not on the trail. It was somewhere below it.

No. That can’t be right. I can’t be there.

I pinched my fingers against the screen and zoomed in to get a clearer look. I could see the words Lost Palms Oasis at the very tip of it. And I was not on it. Not even close. According to the map I was out by at least a mile. I stared at the screen, feeling the cold prickles of horror run down my neck.

Somewhere along the way I had taken a wrong direction… It hit me, then. No one was going to be coming by. No one.

The futility of my situation hit me hard.

Screaming felt like the right thing to do in this situation, but I was at least a mile off the trail, so who the hell was going to hear me? I screamed anyway. It helped to do something.

Above me a hawk had begun to circle, a dark arrow hovering way up high, wings outstretched, scanning the canyon. I watched it. Was it watching me too? Fear ran cold through my blood as I considered where I now fell in the chain of desert life. Potential prey.

The heat pressed down hard, and simply bearing its weight was soul-sapping work. There was no way to know what temperatures I was up against, but at this time of year they reached the 40s Celsius.

It’s the strangest feeling, suddenly knowing how your story is going to end. I pictured my mum being told that I was dead; I imagined mum calling my dad. How long, I wondered, would it take for the news to reach anyone? How long, in fact, it would take before they figured out what had happened to me?

I thought of the world going on without me.

Oh god. I don’t want to die, I really don’t want to die. Panic was going to get the better of me if I let it.

Oh god. I don’t want to die, I really don’t want to die.

As the day progressed, my mind turned to practicalities.

I’d found a little empty Tylenol jar had become useful for urinating into. I was collecting my urine because the alternative – simply tossing the contents off to the side – seemed likely to attract animals. Surely that would be hanging an olfactory banner: HERE IS MY SCENT, COME AND FIND ME!

Collecting it in the bottle meant I could see the colour of my urine, and it looked very dark. Almost reddish in tone. Oh god, was there blood in my urine? Had I damaged my bladder?

All day the sun had been gradually creeping its way closer to the thumb-shaped overhang until it eventually slipped behind it, liberating my face of the burning hot glare.

I felt the relief of having the sun move off the upper half of my body, but also a sudden churn of dread that came with the closing in of the day. Now I was finally beginning to accept the horrifying fact that I may have to spend the night out here.

I do not want to spend the night out here.

DAY 2

I must have fallen asleep eventually, because at some point, I woke up.

A sound had woken me. A rattling.

Dazed by exhaustion I listened intently, trying to figure out what the sound was. It took a moment to realise it was coming from me.

It was my teeth, chattering uncontrollably. A night spent in below-freezing temperatures in a t-shirt and shorts had pushed my body to the edge. My system, I guess, had gone into shock.

Now I was finally accepting the reality: I may have to spent the night out here

My water was almost completely gone. It wasn’t going to be long before urine was all I had. Somewhere in the back of my mind were vague, faded newsprint recollections of stories about people lost at sea or deep in the jungle who had survived by drinking their urine. Had I remembered that right?

Let’s face it. I didn’t have a lot to lose.

I pinched my nose with one hand and, with the other, brought the bottle to my mouth. Lukewarm urine trickled onto my tongue, and down my throat. Pinching my nose harder, I swallowed.

My face screwed up, disgusted. It was bitter, slightly acrid. It was disgusting.

But I could keep it down. And that was all I needed to know.

DAY 3

I thought of my friends. I would have given anything, absolutely anything, to be sitting around talking with them. Just one more stupid conversation. One more round of laughing about something.

I began to cry. Crying was a release, and it was an admission of sorts. I finally admitted to myself how fucking afraid I was.

I began to cry. Crying was a release.

I was tired. So incredibly tired. The pain that consumed my bones and my skin had spread deep into my insides. My kidneys ached, so parched and overworked, forced to recycle urine

over and over again.

My mouth had turned to straw, my lips often sticking to my gums and my tongue rasping across the insides of my cheeks like chalk on a drywall.

I wasn’t hungry. Hunger felt like an entirely fictional concept to me now. What was that like? How strange it was to have forgotten the very notion of eating.

I was drifting in and out.

Weakening. Senses softened.

Semi-conscious. Sounds muffled. Woozy.

I wasn’t always sure when I was asleep and when I was awake.

“FUCKIN’ COYOTE!”

I opened my eyes.

That was a voice. Someone had shouted. It had been so clear, it could have been somebody sitting right there in the canyon with me. But obviously there was no one here.

Had that been a part of my dream, or was it real?

No. Someone had definitely shouted. Something about a coyote. Someone close by.

My heart raced as I strained to hear something. A sound.

Anything.

Wait.

I heard something.

It was the beating of a helicopter.

My breath stopped tight in my chest as I listened for more, daring not to believe that this was real. I’ve probably gone fully fledged mad.

Then that same voice came again, as if out of the sky, as clear as a bell.

“…WE’RE SEARCHING FOR A MISSING HIKER.”

There are moments in life that you never forget. That are seared in your brain like the light through a pinhole camera, capturing something perfectly permanent. And these words hit me like a welcome sucker punch.

I screamed as hard as my lungs could handle: “I’M HERE! HELP MEEEEE! PLEASE!”

I picked up the end of the hiking stick and I waved my sun shade – a tattered white plastic bag – as hard as I could.

I listened for a response, but the sound of the helicopter was growing fainter. The helicopter was leaving.

It was difficult to know how much time passed; it felt like 20 minutes. It could have been five.

And then… I heard it. Yes! The beating of the helicopter. They had come back.

Thank you thank you thank you.

I had to make myself more visible to the search helicopter.

I hung my Bob Dylan t-shirt over the cross of the sun shade. I stretched the tattered white plastic bag across it again making it as big and as white as I could, and I and hung my straw hat on the very top. My flag was now larger.

I felt like I was holding my breath.

And I prayed. Please. Let them come back.

Then the sound.

That glorious sound.

The helicopter had returned.

But I screamed again and again “I’M DOWN HERE! PLEASE! PLEASE! I AM HERE!”

And with it, a voice… they were looking for a missing hiker. Oh my god.

I screamed at the top of my lungs: “PLEASE! I’M DOWN HERE!”

But at first they could not see or hear me. The helicopter would fly over twice more before I would finally hear them say the words I had wanted to hear all this time… That they had seen me.

The world spun like a top.

I am going to live.

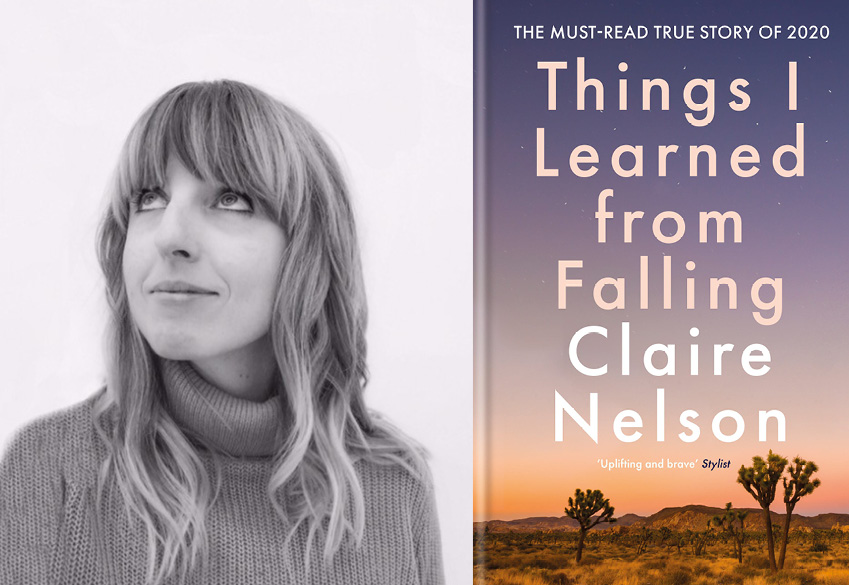

This is an edited extract from Things I Learned From Falling by Claire Nelson (Hachette) which is available now

No Comments