I arrive at my interview with Grace Tame in a taxi I should have refused to take.

I knew it wasn’t right when I went to sit in the back seat, and the driver said firmly, “Sit in the front.” My whole body felt alarmed, but I did as I was told.

His gaze lingered on me, before he asked, “How would you like to pay?”

“By the meter,” I responded curtly, and then looked through my phone for someone to call, as though that could shield me from whatever he might be intending.

But I couldn’t do what my mind was urging me to. I couldn’t make his inappropriate behaviour visible by cancelling the trip, getting out of his cab, not explaining, walking away. I was willing to prioritise him not feeling humiliated over my own sense of safety.

It’s this kind of interaction – this exact emotional state – that Grace has been touring the country relentlessly to expose and explain (though focussing typically on how such interactions develop between children and predatory adults). It’s what she refers to in her new memoir, The Ninth Life of a Diamond Miner, as ‘the disease to please’, and we’ve both grown up with it.

“I have always been… an expert at making adults feel better about their own shitty behaviour, even as a young child,” she writes in her memoir.

I have always been… an expert at making adults feel better about their own shitty behaviour, even as a young child.

I have read her book twice now – first as a friend, to help anticipate any ‘shitty behaviour’ that might come from critics, and the second as a journalist attempting to comprehend a young woman who has become an icon.

It is a profound work. Grace’s memoir is no mere compendium of life events – at 27, she has collected material for several lifetimes. It is a memoir through her mind – one that works circuitously to make sense of the world, traversing the neurodivergent pathways of autism and ADHD.

The book reveals many sides of Grace most Australians know little about.

What is perhaps most stark, aside from her moving depictions of family, is that Grace appears to be naturally good at virtually anything she turns her hand to. The elaborate cover of her book was one she drew herself with a cheap pencil; included within are some of her illustrations from the six-year period she spent living in California. One inserts Monty Python characters into The Last Supper, another is a picture she made for Martin Gore of Depeche Mode, of eleven different hands signing ‘We’re Fucked’.

And it was while living in Hollywood and Santa Barbara that she took up yoga – and became a teacher herself. As her memoir relays, she also runs marathons. She has a photographic memory. And then there’s the unforgettable fact that she was groomed and raped repeatedly by a paedophile who took her for maths extension class – a small class for gifted students.

For a 27 year old who has had their life significantly interrupted and redirected by multiple phases of complex trauma, Grace Tame sure does a lot of things very well.

But if there’s one talent at which Grace truly excels it is her ability to skillfully communicate ugly and complex concepts in a way that has audiences holding their breath.

Earlier this year, we appeared together at the Adelaide Writers Festival. Every square inch of grass at the Pioneer Gardens was crammed with thousands of people – kids who had left school early to be there, even teachers who had skipped their last classes. Grace emerged out of a personal whirlwind to walk onto that stage and hold the audience in the palm of her hand.

After the event, a woman from the audience said she felt like she had been ‘levitating’. As did I. Because that’s how you feel in the company of Grace Tame when she is on stage in full flight. You feel like the whole world is at stake, that every sentence you utter has the power to regenerate and restore, and there is not a moment to waste. I encountered this once before, in a stadium in Cincinnati watching then presidential candidate Barack Obama speak.

—

But when I arrive at the Radisson Blu hotel in Sydney, still kicking myself for capitulating to that sleazy cab driver, I feel conflicted.

Grace’s book had only just been placed on bookstore shelves. It is a day that is at once exciting and terrifying – what will the tabloids make of it? Will there be clickbaity headlines? Grace has deactivated her social media accounts in order to not get distracted by hot takes from gormless accounts, but she can’t turn off the media. Those voices get inside her head and threaten to crowd out her own.

As a journalist, I’m fitting into a tight schedule of interviews which Grace has been doing since sunrise, after more than 18 months of touring and re-speaking her trauma relentlessly.

As a friend, I feel like I should be debriefing with her and Paris, her new assistant (and friend ‘who was with me at Collegiate’, says Grace with eyebrows arched, referring to the private high school that failed to protect her from their paedophile maths teacher, Nicolaas Bester).

It’s entirely artificial to just flip open my notepad and question her, as though we can sit there as a regular journalist and subject. And yet, just as I had in the cab, I ignore the disquiet inside and obey the conventions of my profession. We are on-the-record.

Grace is dressed in immaculate rock chic. Hair drawn back in a tight high braid, leather jacket over a faded Black Sabbath t-shirt, loose slacks and boots that might be Doc Martens. It’s the outfit she will wear on stage that evening at her book launch, hosted not by a celebrity drawcard, but by friend and child sex abuse expert Michael Salter, at the City Recital Hall.

As soon as we’re on-record, Grace shape shifts. She switches from the “autistic artist who finds everyday socialising harder than calculus,” as she describes in her book, “but walking on stage as easy as kindergarten maths.”

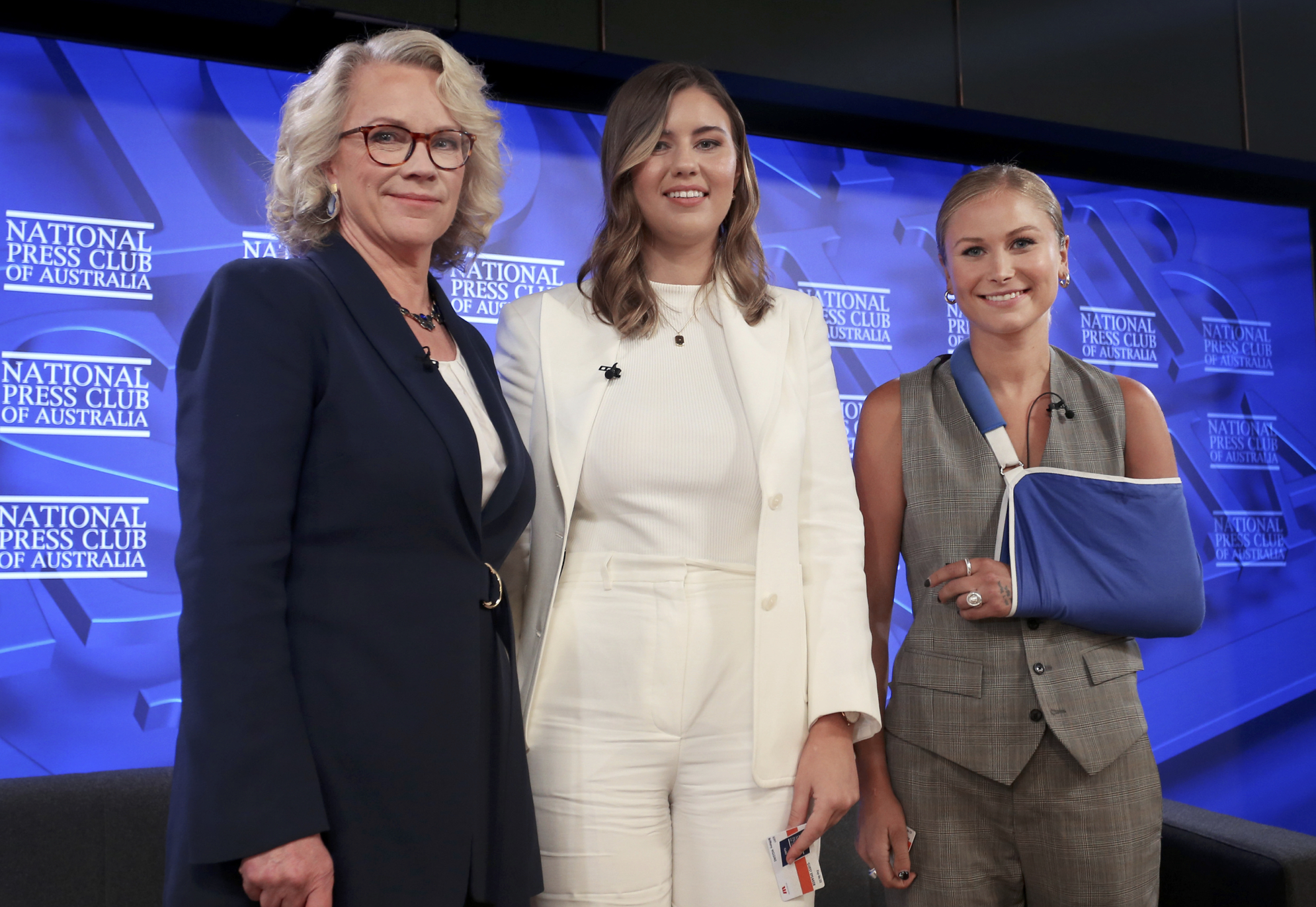

To my question: how does she feel about being lumped into the women’s movement of 2021, as one-of-three (together with Chanel Contos and Brittany Higgins), she responds in the kind of specificity she knows I will need for the page. She is not nervous in interviews, because ‘mimicking’ and ‘masking’ are survival tactics for people with autism which she was diagnosed with shortly after finishing high school.

“On the one hand, it was an immense honour to be part of that conversation, and all the great things that were generated in terms of raising the platform of child sexual abuse in general,” she says.

“But I was very wary of the dangers inherent in lumping together what are in reality, three very different issues and agendas – and three different people. You know, I’ve met Chanel Contos and Brittany Higgins, and we are three very different people from very different backgrounds. Chanel is very well-educated, living in London; Brittany was working in Parliament House.”

I was very wary of the dangers inherent in lumping together what are in reality, three very different issues and agendas – and three different people.

Grace may have been sent to a private school (on a dual scholarship), her mother may have been a television newsreader (on a lower salary than her father, a high-school teacher), but Grace is firmly a product of the Tasmanian working class – and that difference matters.

As a victim of child sex abuse, she is also an advocate for a community of survivors that were not central to the reckoning on sexual violence of 2021 – a community that also includes a great number of boys and men.

“There’s similarities (between child sexual abuse and adult sexual violence), but there’s also key differences. Child sexual abuse is often a persistent crime, it’s predatory, and it’s often between a much older person and a much younger child. I’m not detracting from the experience of sexual assault, but it is usually a one-off, and it disproportionately affects women.

“When we look at child sexual abuse, the statistics are that it’s one in six boys and one in four girls – it still disproportionately affects girls, but to a much lesser extent,” she says.

“The first survivor that I ever connected with, who had been through the experience of grooming, and who took away my, you know, isolation and loneliness, was a man: Steve Fisher, who was the first Tasmanian child sexual abuse survivor to [legally] speak publicly about their own experience [after being granted an exemption to Tasmania’s gag laws, which Grace would later overturn, in collaboration with journalist advocate, Nina Funnell].”

Fisher and Grace would speak for hours late at night while Grace was still in Los Angeles; it was from Fisher that Grace first heard the term ‘grooming’ – a term she has unpacked for tens of thousands of Australians at countless events over the past 18 months.

“It was a man,” she writes in her memoir, “not a woman – a middle-aged burly man – who after seven years of isolation, made me feel like I wasn’t alone…. I would stay up until 3am with my knees tucked into my chest on my tiny concrete balcony, smoking Marlboro Lights, equally saddened and soothed by the sound of someone sharing a past that was so much like my own.”

And yet, despite boys and men like Steve being central to her community of survivors, Grace has been pigeonholed – and even attacked – as a representative of the women’s movement.

It’s not something she rejects out of hand but, as she writes, “I’d rather remain as independent as possible… It’s not that I am a noncommittal causeless rebel, a fraud or a fake; I just really don’t like being labelled.”

I’d rather remain as independent as possible… I just really don’t like being labelled

That resistance to being labelled is a large part of why Grace wrote this memoir. It was an opportunity, after thousands of analysts poring over her words and actions, for her to pore over her own.

“When you tell your story, you have to surrender control and autonomy to the person you tell your story to. They decide what is useful, and the questions aren’t necessarily conducive to telling that key part,” she says.

“That’s something I don’t think the public are aware of. The media itself isn’t just some monolithic beast. So you do get this sort of inconsistent narrative being portrayed. Someone once said to me, ‘Oh, you’ve told 12 different versions of your story’, and I’m like, ‘But, I haven’t. In a lot of the stories that come out, the journalist hasn’t even met me – let alone spoken to me directly. So they misquote me, they get my age wrong – they don’t even bother to look up things like that.”

So how could journalists change their practice to better cover trauma – particularly in this time, when these stories are being told more frequently?

“Put it back in their hands. Ask the survivor, ‘What do you want? What’s important to you?” Because I think that it’s become very ego-driven – it’s what the journalist wants to do. And sometimes it is in good faith, but they think they know what’s best for the survivor. It’s a bit of a Rorschach test; you can’t teach self-awareness, and you can’t get people to realise that they’re not necessarily acting in good faith when they are genuinely convinced that they are.”

One article written recently is a prime example, says Grace. “It was a good story, but the journalist still clearly sees me as a child. We’re still seeing survivors being treated as less than – we’re not seeing them as being equal, let alone people who could teach us something. I’m still being treated like I am damaged, and that you have to handle me with kid gloves. It’s an unconscious bias that has been programmed in over such a long time.”

There will be many words written about Grace’s memoir – some from people who have seriously engaged with this work, others who just have column inches to fill.

But what they write matters less now. Because Grace has taken control of her own story – she is speaking directly to readers now.

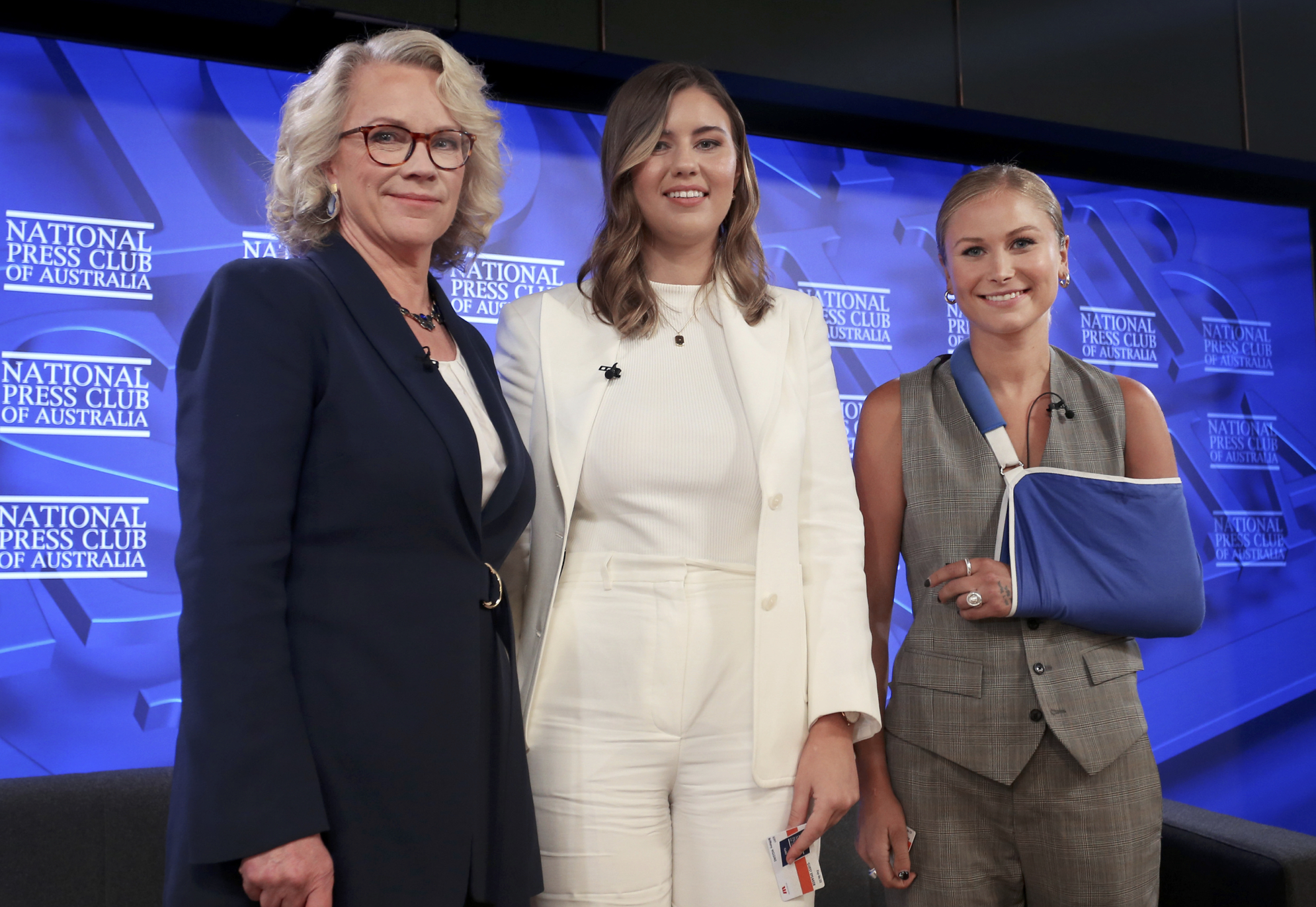

To mine her own nine lives and show the diamonds that glitter brightest – ‘people, places, experiences, love, and connection – and show unflinchingly the hard rock that has concealed them. “I originally wanted to call this book Diamond Miners and Rock Spiders (a slang term for paedophiles),” she writes, “but my editor wouldn’t let me.”

It’s a wild ride. As a peer and a friend, I’m just so damn proud of her.

Grace Tame’s book The Ninth Life of a Diamond Miner (Pan Macmillan) is available now.

Want more stories like this? Sign up to PRIMER’s free weekly newsletter.

No Comments