The stories are so horrific that it’s sometimes hard to believe they’re true.

Human rights activists say that since 2016 the Chinese government has been systematically persecuting its citizens in the northwest of the country. More than one million Uyghurs and other minority groups are thought to have been detained in so-called ‘re-education’ camps, where there’s increasing evidence that they are tortured and brainwashed.

Children are separated from their parents and sent to state-owned orphanages, while women are subject to forced birth control and sterilisation. Between 2017 and 2019, research shows the birth rate fell by almost half.

China has disputed all allegations of mistreatment of the Uyghur population, but in May, UK MPs voted to declare that China is committing genocide in the Xinjiang region. The US and Canada have made similar declarations.

We spoke to three Australian women who have relatives in Xinjiang (which many Uyghurs prefer to call East Turkestan). Two of these relatives have disappeared.

‘They handcuffed my husband and hung him from a door’

Mehray Mezensof, 27 is a registered nurse who lives in Melbourne. Her husband Mirzat Taher, an Australian permanent resident and Uyhgur, has been sentenced to 25 years in prison in China

“The last time I spoke to my husband, Mirzat, on September 26 last year, he was really scared. The police were coming to arrest him at his parents’ home in the capital city, Urumqi, and he was desperate to speak to me before they arrived. I remember him saying on the phone, ‘I don’t know if I’m ever going to see you again,’ and he was begging, ‘Please don’t leave me, I’d rather die than have you leave me.’

I tried to reassure him by telling him that of course I would wait for him – we had a future together. I felt desperate. I just wanted to hug him, to see him.

But he was taken away that day and I haven’t heard anything from him since.

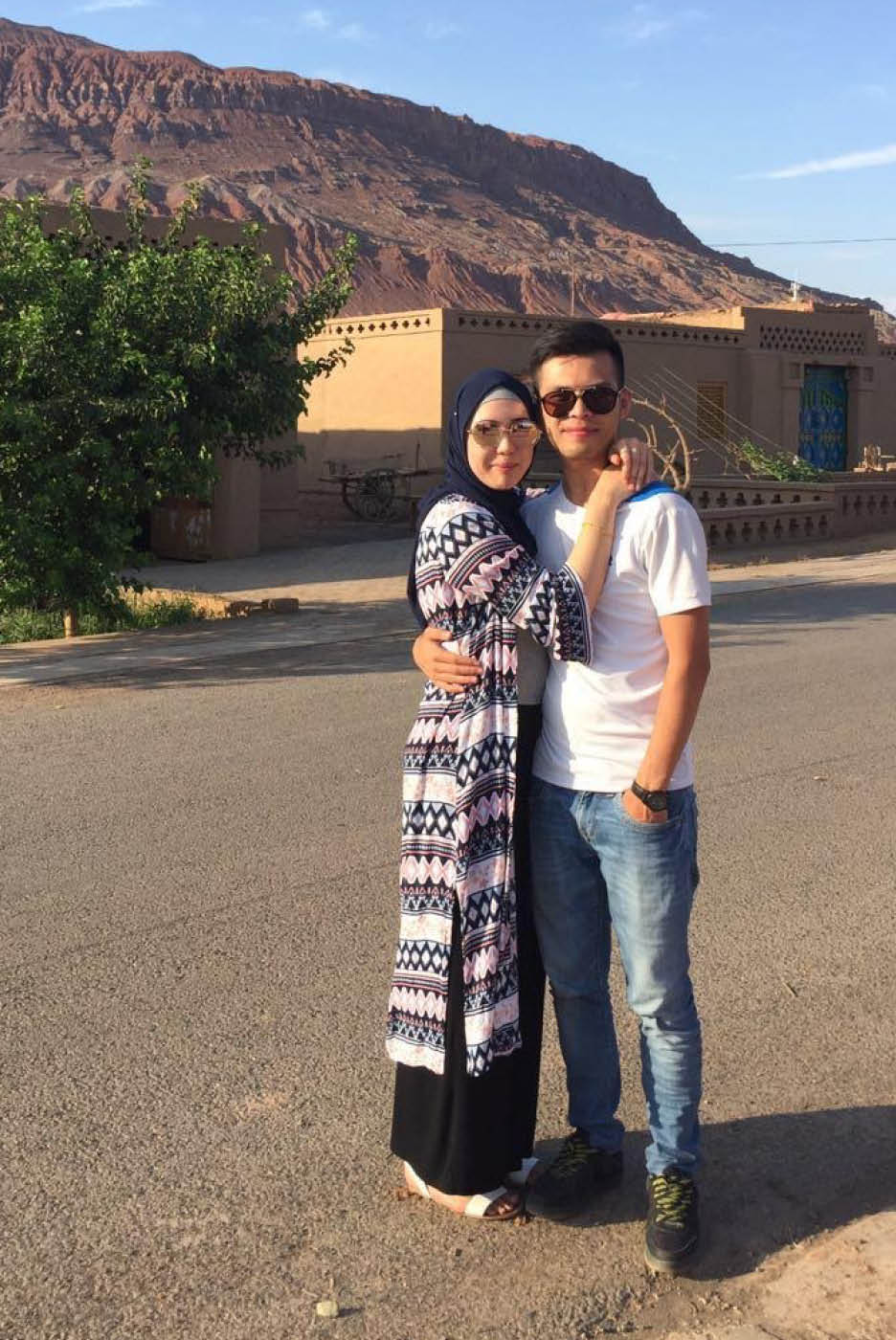

Mirzat and I met online in 2016 and immediately hit it off. My mum and his mum had gone to school together, before my family emigrated to Australia, so our families knew each other. The two of us spoke for three months before I decided to fly to Xinjiang to marry him. Seeing him at the airport, holding a big bunch of flowers, was one of the happiest days of my life. He was even more perfect in real life – funny, caring, really family oriented. Both of us just couldn’t stop smiling.

I’d said early on that I wanted to live in Australia, so we applied for his spousal visa about a month after we married and I lived with him for seven months in Xinjiang. During that time, everything began to change. There were rumours of people disappearing in the middle of the night. The heavy police presence increased, and there were checkpoints everywhere. Officials came into everyone’s homes to make them fill in forms asking about religion, and whether you’d travelled overseas. I had to fill out a form as well, even though I was a foreigner.

We started to worry a bit, but I still didn’t think anything would happen to us. After all, Mirzat had never been in trouble with the police, and these were just rumours. But when his visa for Australia came through, we booked flights to leave 12 days later.

On April 10, two days before we were due to fly, the police came to the house. They confiscated Mirzat’s passport on the spot and told us they were taking him to the police station. He was questioned for three days, and then transferred to a detention centre, where he was to undergo ‘re-education’. Ten months after that, he was transferred to a purpose-built ‘re-education centre’, or concentration camp.

This was meant to be the start of our life together, but instead I felt like I was living in a nightmare. The police were telling us these ‘schools’ were teaching Mandarin and educating people, but my husband speaks fluent Mandarin and has a degree. I felt so scared and worried, and helpless. If we tried to do something, we might end up making it worse for him.

When Mirzat was finally released in May 2019, he’d lost 10 kilograms. He was very pale and weak, and his mental state was poor. I’d had to return to Australia, but I flew back as soon as I could. He talked a bit about what had happened, but not much. He said most of the torture was psychological. He told me that once, he’d accidentally replied in Uyghur to a guard. They handcuffed him and strung him up to a door, and he hung there all day without food. I automatically thought, ‘If he’s told me that, they must have done more that he’s not telling me.’ He had terrible nightmares, scared that they would come for him again.

I’d always managed to extend my visa, but after six months, my application for renewal was denied. I had to return to Melbourne, but we still spoke every day on the phone. Then he was arrested again, held for three months, and released. He hadn’t done anything wrong, but Mirzat believed they hadn’t yet finished with him. On August 30, he was arrested for the final time and made that panicked phone call to me.

I’ve since learned that my husband has been sentenced to 25 years on charges of terrorism.

At first, I remained silent about Mirzat because I thought that if I was compliant the authorities would be lenient, and show some compassion. I worried about what might happen to his family if I spoke out. But I have heard about people disappearing into the Chinese prison system, never to be seen again. So I needed to go public with our story, to let the world know that my husband exists and that he is innocent, and that the government can’t just make him disappear.

‘We stayed silent about my sister because we were scared’

Marhaba Yakub Salay’s sister has been sentenced to six and a half years imprisonment in Xinjiang on trumped-up charges of terrorism

“One morning in October 2017, I woke up to a disturbing WeChat message from my sister, Mayila Yakufu. ‘Please look after our parents and yourself, and everyone in the family, and please don’t contact me anymore,’ she wrote. Shocked, I asked why. She’s 11 years older than me, more like a mum sometimes than a sister, and we’re very close. She said, ‘You have to understand that I can’t give you a reason.’

I was too scared then to try to message her, as we’d heard stories in the previous few months about people being arrested, or simply disappearing. But Mayila hadn’t deleted me from the app. So we developed a kind of code, where I’d post a photo of my baby and she’d post a message to her wall about the weather or something, and I’d know that she was safe. Back then, I didn’t feel so much pain – I thought the government would resolve whatever issue it had, and everything would be ok. I had no experience of this; it hadn’t happened in my lifetime. Then on March 2, 2018, her updates stopped.

We discovered that my sister had been taken to one of the government’s so-called re-education camps, which we call concentration camps. And we were too scared to speak up. We just kept silent because at the time we believed she would be home soon and we didn’t want to put the rest of the family in danger.

Mayila is a single mum with three children and a successful job with a big insurance company. She’s a strong woman, but also soft and always the first to smooth over an argument, even if she isn’t in the wrong. She’d always looked after herself, but the next time we saw her, in video footage, I barely recognised her. Her long hair had been hacked short, and she needed help to stand up, and help walking. She looked sick and so pale.

Mayila was released from the camp at the end of 2018, but arrested again in April 2019. We had no way of getting news about her, as all my friends, relatives and even classmates from school had deleted me from WeChat. My aunt and uncle, who were looking after Marhaba’s kids, were under house arrest. So, I wrote to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade here, to see if they could help. They told me she had been arrested on charges of terrorism, because she had sent money to my parents here in Adelaide to help them buy a house. She has now been sentenced to six and a half years in prison.

She needed help to walk

I want more Australians to know what’s going on in my homeland. About six or seven other countries, such as the UK and US, have recognised that these are crimes against humanity. I hope Australia can follow them, too.”

‘You aren’t allowed to teach your own language to your children’

Ramila Chanisheff is president of the Australian Uyghur Tangritagh Women’s Association

“I became an activist by default. I’d been working overseas and interstate, and when I returned to Adelaide in 2017 everyone was talking about what was happening in East Turkestan, and saying that we had to do something. I immigrated to South Australia with my parents and sister in 1980, but I still have uncles and cousins there.

China is very good at hiding its actions – there’s no freedom of speech or information – so we felt we had to be the voice of the millions that have been forced into camps, or separated from their families. There are up to a million children that have been taken into state-run orphanages and raised as Han Chinese. It’s mainly the very young that are taken, kindergarten age; it’s easy for the authorities to erase their history and heritage I suppose. They might forget who they are as they grow.

Even if you’re not in a forced labour camp, life in East Turkestan is stifling. There are military checkpoints everywhere. Police can come into your house at any time, to ask questions like, ‘Do you pray? Do you have a Qu’ran?’ You aren’t allowed to teach your own language to your children. In order to enforce this, the Chinese authorities introduced a ‘family’ or ‘friendship’ policy, where an official can come into your house to stay. So for example, the husband might have been taken away to a camp, the wife is at home with their children and a stranger moves in with them. The wife has to cook and clean for this man, buy new towels and sheets, and have everything ready. This is the kind of control they have.

We want the government to adopt Magnitsky-style targeted sanctions, which punish individual perpetrators of serious human rights abuses. They can be used to target high-ranking officials by seizing their overseas assets and ban entry to Australia. We should also expand anti-slavery laws to prevent products produced using forced labour entering our supply chain. Other countries are also talking about a diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Olympics next year.

There’s huge anxiety and depression among the Uyghur community here. I’m forever crying with every horrific story I hear. If the international community doesn’t act soon, we will lose a generation and our culture. We have to speak out, and we have to live with hope.”

As told to Felicity Robinson

Amnesty International is petitioning for the release of Marhaba and Mirzat

No Comments